Search

CATEGORIES

We found 90 books

We found 1139 news items

We found 90 books

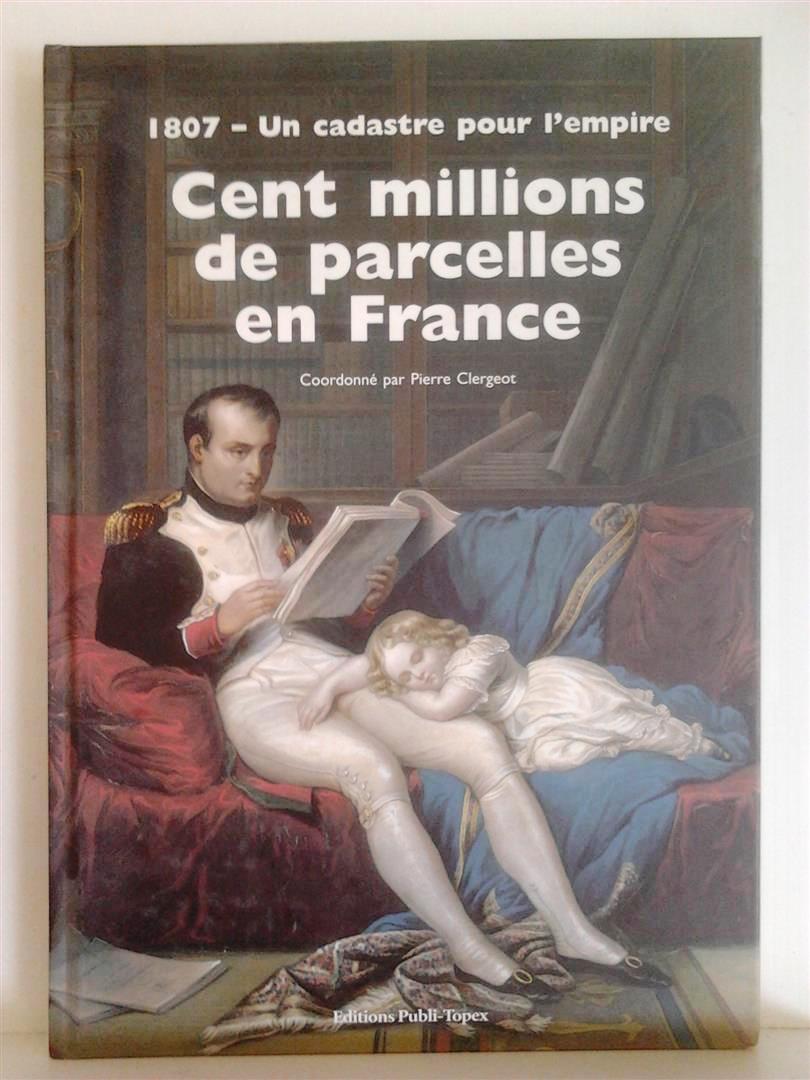

Cette biographie explore la vie et le règne de Napoléon III, le dernier monarque de France. L'auteur, BAC Ferdinand, est un historien renommé pour son travail sur l'histoire française. Dans ce livre, il présente une image différente de Napoléon III, loin des stéréotypes habituels. Il dépeint Napoléon III comme un homme complexe, plein de contradictions, mais aussi comme un leader visionnaire qui a eu un impact significatif sur la France. Le livre est bien documenté, avec de nombreux détails historiques et des anecdotes fascinantes. Il offre une perspective unique sur une figure historique souvent mal comprise.

"Der Mensch aller Zeiten" ist ein zweiteiliges Werk des Autors Dr. Ferdinand Birtner. Es handelt sich um eine umfassende Studie über die Geschichte der Menschheit, in der Birtner die Entwicklung des Menschen von den frühesten Zeiten bis zur Gegenwart nachzeichnet. Dabei legt er besonderen Wert auf die Darstellung der kulturellen, sozialen und geistigen Errungenschaften der verschiedenen Epochen. Das Werk ist sowohl für Historiker als auch für interessierte Laien eine wertvolle Quelle und zeichnet sich durch seine detaillierte und fundierte Darstellung aus.

"De gluurster" is een roman van de Frans-Algerijnse auteur Nina Bouraoui. Het verhaal is een diepgaande verkenning van de vrouwelijke identiteit en seksualiteit tegen de achtergrond van de Algerijnse samenleving. De roman volgt het leven van een jonge vrouw die opgroeit in een streng islamitisch gezin en worstelt met haar verlangens en haar plaats in de samenleving. Door haar ogen krijgen we een intiem en vaak pijnlijk beeld van de onderdrukking en het geweld waarmee vrouwen in deze context te maken krijgen. Het boek biedt een uniek perspectief op de complexe interactie tussen gender, religie en cultuur in Algerije. Dit maakt het een waardevolle bron voor historici die geïnteresseerd zijn in genderstudies, postkoloniale studies en de moderne geschiedenis van Noord-Afrika.

'Dood op krediet' geeft van binnenuit inzicht in de mentaliteit van de kleine middenstand, die in de jaren 30 en 40 tot de bekende gevolgen heeft geleid: sociale rancune, massahysterie tegen een willekeurige zondebok, ondergangs-mystiek en gefascineerd-zijn door geweld. Frans van Woerden drukt het zo uit: 'Elke zin is een geladen revolver'.

17de druk. Paperback, in-8, 560 pp.

17de druk. Paperback, in-8, 560 pp.Deze inktzwarte roman, geschreven in een radicaal nieuwe en beklijvende stijl, verhaalt in geromantiseerde vorm Célines wederwaardigheden vanaf het begin van de Eerste Wereldoorlog tot aan het moment van publicatie van de roman. Opbouw: WO I, kolonie, New York, Detroit (Ford-fabrieken), Parijs (dokter in achterbuurt). De invloed van Céline op de literatuur kan nauwelijks overschat worden (Sartre, de romans en de filosofie van Camus en meer recent Philippe Claudel). De voortdurende afwisseling tussen een gedurfde introspectie en een beschrijving van de absurditeit van de omgeving en de handelingen van anderen, maken deze roman tot een unicum. Het leven als een nachtmerrie zonder uitweg. Bekroond met de Prix Renaudot. Louis-Ferdinand Céline (Courbevoie, 27 mei 1894 - Meudon, 1 juli 1961) was het pseudoniem van de Franse schrijver Louis Ferdinand Destouches.

Céline beëindigt het manuscript op 30 juni 1961 en overlijdt de dag nadien. Als geen ander schakelt hij midden in zijn verhaal plots over naar de actualiteit: "Geëerde lezer, vergeef mij, de Kongolese zaken trekken weer wat bij, de winsten in de zak gestoken, de verliezen bejammerd, de verneukte hazen ziek op bed ... (...)" (96) C. verwijst naar het débâcle van het kolonialisme in Belgisch Congo en de perfide rol van de journalisten: "berijden alle oude paradepaarden, zwepen ze op om de grootste nonsens te komen uitkramen, leven in de brouwerij te brengen, die slapende bars wakker te schudden, (...)"

In zijn nawoord komt Van Woerden uit bij het racisme van Céline: "Het is of zijn racisme zijn uiterste consequentie heeft bereikt: de veroordeling van het menselijk ras."(243) Als het van C. afhing dan werd de reproductie van deze mislukking definitief stopgezet. Het is een idee waarmee u een tijd bezig bent, of u dat nu wilt of niet.

Céline décrit - deux ans après la parution de 'Voyage au bout de la nuit (1932) - l'abattoir international en folie: 'J'ai attrapé la guerre dans ma tête.'

![Book cover 19910169: CELINE Louis-Ferdinand [Louis-Ferndinand DESTOUCHES] | Je vriend met alle stekels uit. Briefwisseling met zijn uitgever. (selectieve vertaling van Lettres à la NRF 1931-1961)](https://www.mers.be/COVERS_MERS/19910169.jpg)

Hardcover, relié, 4to, 380 pp., illustrations de Tardi.

Hardcover, relié, 4to, 380 pp., illustrations de Tardi.Voyage au bout de la nuit est un récit à la première personne dans lequel le personnage principal raconte son expérience de la Première Guerre mondiale, du colonialisme en Afrique, des États-Unis de l'entre-deux guerres et de la condition sociale en général.

Ferdinand Bardamu a vécu la Grande Guerre et vu de près l'ineptie meurtrière de ses supérieurs dans les tranchées. C'est la fin de son innocence. C'est aussi le point de départ de sa descente aux enfers sans retour. Ce long récit est d'abord une dénonciation des horreurs de la guerre, dont le pessimisme imprègne toute l'œuvre. Il part ensuite pour l'Afrique, où le colonialisme est le purgatoire des Européens sans destinée. Pour lui c'est même l'Enfer, et il s'enfuit vers l'Amérique de Nord, du dieu Dollar et des bordels. Bardamu n'aime pas les États-Unis, mais c'est peut-être le seul lieu où il ait pu rencontrer un être (Molly) qu'il aima (et qui l'aima) jusqu'au bout de son voyage sans fond.

Mais la vocation de Bardamu n'est pas de travailler sur les machines des usines de Détroit; c'est de côtoyer la misère humaine, quotidienne et éternelle. Il retourne donc en France pour terminer ses études de médecine et devenir médecin des pauvres. Il exerce alors dans la banlieue parisienne, où il rencontre la même détresse qu'en Afrique ou dans les tranchées de la Première Guerre mondiale.

Quelques adjectifs peuvent qualifier le roman :

antinationaliste/antipatriotique: le patriotisme (ou le nationalisme) est, selon Céline, l'une des nombreuses fausses valeurs dans lesquelles l'homme s'égare. Cette notion est visible notamment dans la partie consacrée à la Première Guerre mondiale, au front, puis à l'arrière, où Céline s'est fait hospitaliser;

anticolonialiste: clairement visible lors du voyage de Bardamu en Afrique, c'est le deuxième aspect idéologique important de l'œuvre. Il qualifie ainsi le colonialisme de « mal de la même sorte que la Guerre » et en condamne le principe et l'exploitation des colons occidentaux, dont il brosse un portrait très peu flatteur et caricatural ;

anticapitaliste: sa critique du capitalisme transparaît nettement dans la partie consacrée aux États-Unis, lors du voyage à New York, puis à Détroit, principalement au siège des usines automobiles Ford. Il condamne le taylorisme, système qui « broie les individus, les réduit à la misère, et nie même leur humanité », en reprenant sur ce point quelques éléments de Scènes de la vie future (1930) de George Duhamel, qu'il a lu au moment de l'écriture du Voyage. Le regard qu'il porte sur le capitalisme est étroitement lié à celui qu'il accorde au colonialisme ;

anarchiste: à plusieurs reprises, l'absurdité d'un système hiérarchique est mise en évidence. Sur le front durant la guerre, aux colonies, à l'asile psychiatrique... l'obéissance est décrite comme une forme de refus de vivre, d'assumer les risques de la vie. Lorsque Céline défend son envie de déserter face à l'humanité entière, résolument décidée à approuver la boucherie collective, il affirme la primauté de son choix et de sa lâcheté assumée devant toute autorité, même morale. Cette vision teintée de désespérance se rapproche de la pensée nihiliste.

src: wiki

Additional images

Magazine, 143 pp., illustrations, carte des abbayes cisterciennes en France.

Magazine, 143 pp., illustrations, carte des abbayes cisterciennes en France.We found 1139 news items

click on the images to download them in high res

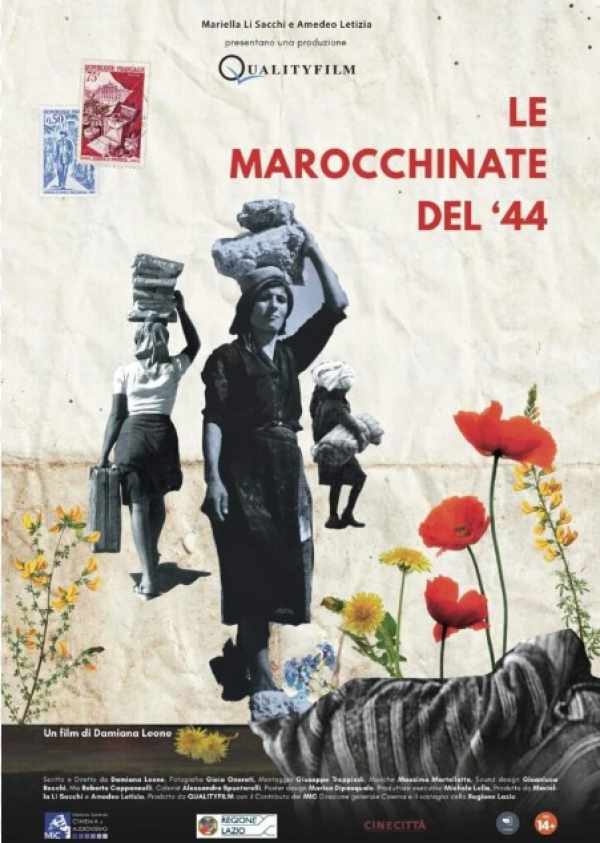

Le marocchinate del '44

original title:

Le marocchinate del '44

directed by:

Damiana Leone

cinematography:

Gioia Onorati

editing:

Giuseppe Treppiedi

music:

Massimo Martellotta

producer:

Mariella Li Sacchi, Amedeo Letizia

production:

Qualityfilm

country:

Italy

year:

2023

film run:

81'

format:

colour

status:

Ready (01/05/2023)

More than 75 years have passed since that series of frightening events that go by the name of Marocchinate: a sliver of the horror of colonialism that arrived in Italy by the will of the French army and still not recognized as War Rape and therefore as a crime against humanity. The theme is very current even if in no conflict even more recent and in even remote places we have reached figures like those of our documentary: 20,000 women victims of violence and an unspecified number of men and children.

Today that dormant memory seems to have been rediscovered and there are numerous events that try to give it life and voice, both locally, nationally and internationally.

The decision to make a documentary on “Marocchinate” (Morocconized, could be a translation in English) women starts primarily from the author's personal need to conclude a long journey of research. But even more the project stems from a historical necessity, given the incompleteness or inaccuracy of many aspects, of the few existing documentaries on the subject. In fact, the point of view is always very masculine, sometimes very military, and in any case never internal, on the part of those who know those facts by family. A constant mistake that is made is on the figures (who says 50,000, who 3,000), or even to identify the Marocchinate women with "the Ciociara", in particular the film, when Moravia himself declared that it was not a novel about the Moroccan ones. The historical facts in fact diverge greatly from the film story.

The documentary therefore tells this story from the inside, from the point of view of the victims and from the point of view of the executioners (the French colonial military, always omitted in previous narratives).

Details about the victims emerge: how they lived before the war, how they experienced the violence, and what their life was like as Marocchinate, if they received the war pension, how the children of those raped women lived, if there were . The effects of mass rape on the population also emerge after more than 70 years, demonstrating that that violence remains silent and yet always present. The story of the Marocchinate women is also an opportunity for generations and nations to meet, through the female gaze. It is also the story of an encounter and integration through historical research. It is also an opportunity to talk about contemporary war rape, of a legislation still lacking at the international level.

Une fois n’est pas coutume, je vais lire comme je le faisais dans les Assemblées lorsque le temps était minuté. Je le ferai d’autant plus que j’ai appris très récemment que je parlerais le dernier. Je demande à chacun d’entre vous ce que ça lui ferait de savoir qu’il parle après Abdourahman Waberi et Annie Ernaux. Il faut donc que l’émotion reste contenue dans la stabilité de l’écrit.

Car parler après vous tous, est une mission singulière.

Comme vous tous, je crois à la force de l’esprit humain, à la gloire de ses expressions, à la continuité de ses efforts d’émancipation.

Je le sais comme vous, que quand l’humanité, comme c’est le cas aujourd’hui, cherche son chemin à tâtons, les consciences librement insoumises par l’effet de l’art et des sciences, marchent sur nos premiers rangs.

Voilà pourquoi un homme politique peut se sentir dérisoire au moment de parler après vous tous, après Abdourahman Waberi, après Annie Ernaux.

Mais les lieux eux-mêmes aussi, pour peu qu’on soit capables de ressentir l’Histoire, et pas seulement de l’étudier et de la connaitre, ces lieux ajoutent au sentiment étrange qui m’a pris en préparant ce texte.

Ce réfectoire a reçu, à partir d’avril 1790, « la Société des Droits de l’Homme »…. et du Citoyen » sans lesquels ces droits ne sont rien. Cette société que l’on a surnommée ensuite le « Club des Cordeliers ».

Ici ont parlé avant nous George Danton, Camille Desmoulins, Jean-Paul Marat, Hebert, Chaumette. Des noms qui pour beaucoup d’entre nous, dans l’ensemble de la Révolution, claquent comme des drapeaux.

Cela vous le saviez.

Mais combien savent ici que s’exprima aussi le seul mouvement politique, féminin et féministe, de toute la Révolution. Celui qui s’assemblait dans la « Société des citoyennes républicaines révolutionnaires » de Paris. Non seulement Théroigne de Méricourt, mais Pauline Léon, chocolatière et Claire Lacombe, actrice.

Elles animaient ce groupe révolutionnaire, non mixte. Elles réclamaient le statut de citoyennes et le droit…. au port d’armes pour former des brigades féminines de défense de la révolution.

Encore une fois, le nom des femmes du peuple et leur radicalité a été effacé et souvent remplacé par celui des femmes de la haute société, toujours mieux recommandées, à leur époque comme à la nôtre.

Certes ces clubs furent ensuite indignement interdits. Mais, les femmes révolutionnaires, du temps de leur action, ont donné son sens complet à la grande révolution de 1789 !

Leur silence aurait relativisé, amoindri l’onde de choc qui travaille encore ce peuple et une partie du monde, et qui a jailli de la grande révolution de 1789.

Dans cette salle, on a voté avant l’Assemblée et avant toute autre organisation, la déchéance du roi après sa fuite à Varennes. Ici on a lancé la première pétition pour la proclamation de la République en France.

Ainsi, les voix entendues avant moi et les lieux qui nous reçoivent ont ouvert un chemin. Et nous venons assumer la continuité de son fil conducteur sous l’égide d’Etienne de la Boétie.

II

Le jeune insoumis du seizième siècle, écœuré par la barbarie de la répression des « pitaux », les piteux, pauvres gens s’insoumettant à la taxe sur le sel, rédigea à 18 ans le discours montrant comment les tyrans et les monarques de toutes sortes sont d’abord forts de notre soumission.

Il montre comment cette soumission devient volontaire quand nous choisissons de faire taire l’instinct de liberté qui nous anime tous comme tout être vivant, humains et bêtes.

Lui, puis Marie de Gournay plaidant à la même époque « l’égalité des hommes et des femmes » devant la reine Médicis, c’étaient parmi d’autres, en pleine nuit des guerres de religions, la petite cohorte fondatrice de ce qui deviendra le siècle des Lumières, puis de la grande Révolution qui a eu un de ses nids dans ce lieu.

Eux, affrontait alors un obscurantisme alors hégémonique qui combinait, de la naissance à la mort, un pouvoir religieux avec un pouvoir politique.

Eux, affirmaient et argumentaient la thèse d’une idée radicale que nous continuons de faire vivre. Celle du manifeste de Pic de la Mirandole « sur la dignité de l’Homme ». Il voulait dire de l’être humain. L’idée qui travailla les consciences dans le siècle des Lumières puis culmina avec la Déclaration des droits et enfin avec la Commune de 1871 : l’être humain est son propre auteur.

Rien d’autres que sa liberté ne fera jamais son Histoire. Il lui revient donc de savoir librement et rationnellement s’il doit se soumettre ou bien s’insurger.

Il a ses repères : les droits fondamentaux de la personne humaine sont inaliénables ! Ils forment la seule base légitime qui doit tenir lieu de règle à tout pouvoir politique. Il doit les servir et les satisfaire.

Liberté, savoir, raison : les trois convergent dans la revendication d’égalité des droits sociaux pour y accéder. Cette feuille de route reste la nôtre.

III

Car à notre tour, nous affrontons un obscurantisme. C’est la doctrine néolibérale. Elle exige de nous une soumission complète à un ordre économique destructeur de l‘humain et de la nature au nom d’une pure superstition.

C’est la foi dans l’existence d’une « main invisible », celle du marché, seule capable, en tous points et sur tous les sujets, de répondre aux besoins humains. Bien sûr, il s’agit d’une idéologie dominante, venant après d’autres. Bien sûr elle est au service de la classe dominante. Mais elle est peut-être l’obscurantisme le plus prégnant qu’on ait jamais connu.

Car si les idées professées sont comme à l’accoutumée une justification de l’ordre existant, celles-ci s’incrustent dans notre corps, jusque dans nos manières d’agir nos gouts et nos comportements.

Nombre d’entre nous ici pensons que la phase ascendante de cette idéologie est achevée. L’impasse sur laquelle elle débouche à la vue de tous gagne les consciences.

Mais l’ampleur des dégâts dans le saccage de la nature comme dans la destruction des sociétés est considérable. Son effet est maintes fois irréversible, qu’il s’agisse du dérèglement climatique ou de l’extinction de la biodiversité.

De la baisse de la fertilité, le recul de l’espérance de vie en bonne santé, de la multiplication des zoonoses, et l’obscénité des fortunes face aux masses de dénués de tout, quand une personne dans ce pays possède autant que 20 millions d’autres, nous font voir l’amorce d’une crise de la civilisation humaine. Au moins une aussi fondamentale que connut celle de l’Ancien Régime.

Et cela au moment où le blocage des relations internationales par la logique de compétition pour l’appropriation des matières premières et la domination politique, mettent de nouveau à l’ordre du jour la possibilité d’une guerre totale et mondiale.

Absurde, ce système est capable de se nourrir de ses propres dévastations. Il est donc incapable d’assumer l’intérêt général. Il doit être remplacé au nom de cet intérêt général humain. Les conditions pour le faire sont dans l’émergence d’une volonté politique écologique et sociale majoritaire.

Elle ne peut se construire sans la contribution décisive d’une pensée critique globale alternative. Notre ambition, dans cette Fondation, est là.

IV

La doctrine néolibérale est un obscurantisme au sens littéral et radical du terme. Elle l’est dans tous les cas où le mot peut s’appliquer. Par exemple quand elle voudrait faire croire que l’histoire accomplit un destin déterministe.

Le terminus, la « fin de l’histoire », ce serait l’instauration du marché dans tous les domaines. Ennemi des règlements et des lois, la doctrine néolibérale est alors d’abord l’ennemie du pouvoir citoyen qui les formule. Le néolibéralisme a une vocation autoritaire du fait même de ses prémices. Mais il avance masqué.

Le plus grave vient quand on mesure, et dans ce moment d’esprit je le souligne, quelle inversion du sens de l’histoire de la pensée il met en œuvre. Ainsi quand l’idéologie néolibérale domine le champ de la production des savoirs.

Le néolibéralisme agit alors en ennemi du savoir scientifique quand il paralyse ou interdit la libre circulation des connaissances en les privatisant. Et quand il entrave de cette façon l’effet de culture cumulative pourtant à l’origine de la civilisation humaine !

Telle est la situation dans laquelle nous vivons avec la généralisation des brevets à la suite des accords de l’OMC en 1994. Ce droit de propriété sur les connaissances et les découvertes a été multiplié par trois.

Alors a explosé le nombre des domaines du savoir soumis au régime de la propriété privée exclusive des détenteurs de brevets.

Les questions les plus sensibles sont impliqués.

Ainsi depuis 2001 plus de 50 000 demandes de brevets ont été déposées sur les séquences génétiques ! L’office européen des brevets a déjà accepté en 2015 un brevet sur une tomate et une variété de brocoli. C’est un début. De nombreuses autres demandes existent. Elles reviennent à vouloir créer un droit de propriété privée sur des espèces entières de nombreux organismes vivant.

Il s’agit là d’une tendance de fond. Elle accompagne le développement d’un capitalisme tributaire vivant davantage de propriété intellectuelle abusive que de prouesses dans la production et l’investissement.

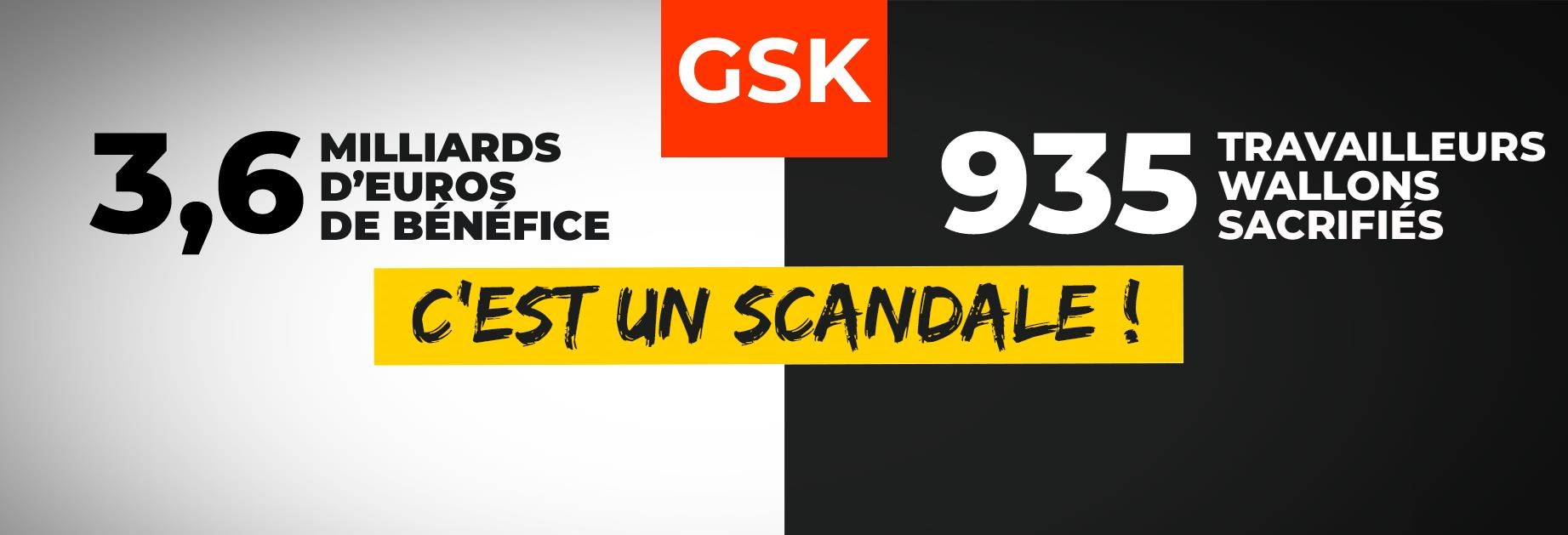

La conséquence de cet obscurantisme s’est constatée à propos des vaccins pendant la pandémie de covid19. Ici rappelons d’abord comment le partage gratuit par les chercheurs du monde entier des connaissances sur le virus est à l’origine ensuite de l’activité des laboratoires privés.

Ces derniers se sont pourtant approprié le bénéfice de la mise au point et de l’exclusivité de la vente des vaccins !

Cette vente limitée aux pays riches a permis mille dollars de bénéfices par seconde sans aucun retour sur la recherche publique qui l’a rendue possible ! Mais doit-on oublier comment, jusqu’en 1959, il était interdit en France de déposer un brevet sur un médicament ? À L’époque le savoir scientifique se partageait gratuitement et universellement.

Dans ce registre du poids du « marché » sur l’avancée du savoir, doit-on aussi oublier comment les recherches sur cette famille de virus furent abandonnée en France parce qu’elles n’offraient pas de perspective rapide d’entrée sur le « marché » ?

Ou bien, à l’inverse comment l’entreprise MG en déposant deux brevets sur deux gènes associés au cancer du sein a obtenu le droit d’interdire ainsi toutes les recherches sur ces deux gènes par les laboratoires hospitaliers et universitaires ? L’usage des tests ainsi produits par MG sont facturés entre 3 et 4000 dollars.

Le caractère criminel contre l’Humanité de la rétention des savoirs est avéré quand on apprend comment des compagnies pétrolières ont caché pendant quarante ans leurs connaissances scientifiquement établies sur les conséquences climatique désastreuse du recours aux énergies carbonées.

Obscurantisme ! Quand la précarité des chercheurs bride leur liberté, quand les appels à projets minent les financements pérennes de leurs travaux. Quand ils donnent le pouvoir au temps court de la rentabilité sur le temps long du savoir fondamental. Oui, le temps long. On n’a pas inventé l’électricité en essayant d’améliorer la bougie. Quand le crédit d’impôt recherche a pour premiers bénéficiaires la grande distribution du commerce et la banque.

Freiner la connaissance, empêcher la circulation des savoirs, rentabiliser l’ignorance, tel est la verité de cet obscurantisme néo libéral.

V

Le néolibéralisme est un obscurantisme quand il professe la nécessité d’une croissance productiviste sans fin dans un monde aux ressources finies

Et encore quand il prône l’attribution d’un prix à la nature. Mais ! Ni la composition de celle-ci, ni les conditions de sa pérennité ne peuvent se dissocier. Ils ne peuvent donc en aucun cas s’évaluer au détail !

Ne faudrait-il pas aussi qualifier cet obscurantisme de « criminel » quand il suscite des consommations qui rendent malades d’obésité et de diabète des millions de personnes, pour ne rien dire des cancers. Et cela en consacrant des sommes considérables à injecter des besoins artificiels par l’envoutement publicitaire.

N’est-ce pas un obscurantisme de prêcher le contraire de ce que montrent les faits concrètement observables ? Ainsi quand il prétend organiser toute l’activité de la société par le système des prix et de l’échange marchand ? Ou quand il intime à l’État de se retirer pour « favoriser l’entreprise privée » et sa folle « énergie ».

Non, l’activité humaine ne correspond que bien rarement à des critères de marché. Et sans doute l’activité humaine n’est-elle réellement humaine que quand elle est absolument gratuite, c’est-à-dire sans attente d’un retour sur investissement.

Et les domaines où il s’instaure désormais sont aussitôt en proie au chaos ! On le voit pour l’énergie ou les transports, l’éducation ou la santé. Autant de domaines ou l’économie de marché provoque des pertes de savoirs et de savoir-faire. Au prix d’un recul net de l’efficacité du service.

Non, l’État n’a jamais été aussi présent qu’aujourd’hui dans le financement, à perte, de l’économie de marché. Aujourd’hui il y injecte en France davantage d’argent dans les entreprises sans aucune contrepartie qu’au temps où il finançait la planification économique.

Aujourd’hui l’État donne davantage aux entreprises qu’aux ménages. Mais sa ponction est plus grande sur les ménages que sur les entreprises.

Le discours néolibéral est donc une négation du réel, un rideau de fumée pour masquer un détournement massif de fond public au service de la cupidité qui accumule sans aucun retour sur la société.

Voilà ce qui pourrait se définir aussi comme une forme particulière du parasitisme.

La légitimation des inégalités et de la prédation cupide sous couleur de loi de la nature économique et leur donner la figure d’une discrimination naturelle par le racisme, par le sexisme. N’est-ce pas ce que nous entendons par un obscurantisme social ?

VI

J’ai répété le mot « obscurantisme » parce que j’ai voulu dans ce moment où nous installons solennellement la fondation La Boétie, lieu d’esprit critique, souligner l’inconciliable qui sépare notre travail du néolibéralisme et de l’idéologie du marché capitaliste par tout et pour tous.

Notre sujet est la plénitude de l’être humain. Son accès à l’harmonie avec ses semblables et avec la nature. L’idéologie néo libérale et le marché réduit l’humain à la marchandise qu’il contient : sa force de travail. Il cherche à l’utiliser sans limite tout en la dépréciant sans cesse.

Nous en avons l’exemple sous les yeux avec la réforme des retraites. Elle prétend que le seul temps socialement utile serait le temps contraint de la production. Sans discuter aucun des aspects de cette réforme, je veux pointer comment il y a pour eux une légitimité évidente à vouloir davantage au temps libre et aux fonctions sociales et culturelles qu’il accomplit dans la vie. Une décision à rebours du progrès historique qu’a représenté la diminution par deux du temps de travail depuis un siècle et la multiplication par 50 de la valeur produite.

C’est un obscurantisme de demander de travailler plus pour produire plus. Non, il faut travailler moins pour travailler tous et mieux et réduire la part incroyable du gâchis dans la production, la distribution et la consommation. Gâchis masqué, nié parce qu’il est compté comme un « plus » dans le PIB. Un Français consomme 26 kilos d’équipement électrique et électronique par an et doit en jeter 21 kilos la même année.

35% des dix millions de tonnes de déchets alimentaires par an sont perdus dans la production des industries agro-alimentaires et dans la distribution commerciale.

L’idéologie néolibérale est un système d’idée au service d’un régime politico-économique qui réduit les êtres humains à une seule fonction : consommer, et à un seul statut socialement utile : être un client et bien sur un client actif.

Quel monde alors ! Un monde où règne une seule valeur, une seule norme, une seule beauté à contempler, un seul désir légitime à exprimer sans limite. C’est la marchandise !

La marchandise est devenue un absolu, un idéal. Toujours disponible, toujours légitimement exigible, sécable, transportable, évaluable en monnaie, provisoire mais répétitive comme le désir qui en est la source, jetable aussi, comme tout ce qui encombre le besoin déjà satisfait.

La marchandise n’est pas un « en dehors de nous » mais un rapport social et intime qui peut tout englober tout reformuler l’être humain s’il n’y prend garde et n’allume pas les lumières de la raison face à l’obscurité des pulsions de la consommation.

Les modes d’emplois y sont une culture, une façon de se comporter, un signal de conformité sous le regard des autres. Les possessions y sont une sculpture de soi. Dans ce monde, l’être humain, ses contradictions, ses fantaisies, ses raisons et ses déraisons, dans cette complétude que je viens de nommer, dans ce désordre fécond qui est simplement la vie est une espèce en voie de disparition.

Quand l’avoir devient la seule manière d’être, le consommateur absorbe l’humain, le client efface le citoyen, la pulsion remplace la raison. Triple néant de sens humain. Triple disparition de l’humain.

A côté du transhumanisme qui prêche une hypothétique perfection individuelle là où nous, depuis Pic de la Mirandole et La Boétie mais surtout depuis Rousseau croyons à la perfectibilité collective permanente, voici surgir l’inhumanisme néolibéral. Il n’y a plus d’êtres, il n’y a plus d’échanges, il n’y a que le marché.

C’est le monde ou l’humain organise sa disparition comme sujet de son Histoire. C’est le monde qui s’évalue dans le niveau du PIB ou ne compte aucune des choses importantes : ni le niveau d’éducation, ni l’état de l’environnement, ni la santé des populations, ni le bonheur de vivre.

C’est la doctrine qui fait de ses pulsions et de ses désirs préfabriqués le tapis roulant de l’accumulation capitaliste.

VII

En face de quoi l’esprit critique que nous construisons et que nous voulons construire, chacun à notre manière, dans la liberté absolue de notre diversité, chacun part le chemin de ses propres savoirs, formule un Nouvel Humanisme.

La vie de l’esprit est notre front de lutte.

Notre fondation assume le projet d’être entièrement au service de la pensée critique du système dans lequel nous vivons.

Sans les outils sérieusement élaborés de cette pensée critique on ne peut comprendre ce qui se passe et encore moins sortir de l’impasse dans laquelle le système a enfermé l’humanité.

Ainsi que l’a formulé Kant : le pratique sans la théorie est aveugle, la théorie sans la pratique est absurde.

Et de cette manière, nous pensons formuler, au fil du travail de pensée, un « nouvel humanisme ».

Celui de notre temps. Bien sûr il dit de nouveau que les êtres humains sont les seuls auteurs de leur histoire et de leurs êtres. « les humains sont tels que les a fait leur culture » dit La Boetie Mais il le fait en assumant l’implication complète de l’humain avec tout le vivant dans un destin commun qui ne sépare pas les humains des animaux, ni d’une forme quelconque de la vie.

Et il doit le faire en documentant sans trêve l’absurdité dévastatrice du système. En produisant dans tous les domaines les éléments de compréhension alternative capables de nourrir l’action citoyenne et de reformuler la décision politique.

La pensée critique que nous travaillons est notre arme de démystification massive contre un système idéologique et un système économique basé sur le mensonge et l’abus de bien social et naturel.

Et c’est à la Boétie qu’il me faut emprunter pour un slogan de fin de discours dans le contexte de la grève générale de mardi prochain qui sera un grand moment d’esprit populaire. Et du grand rassemblement samedi prochain 11. Car personne ne s’y trompe, le refus de la retraite à 64 ans, c’est le refus d’un monde Nous qui ne voulons ni de la retraite à 64 ans ni de son monde, de cœur, de corps d’esprit, cessons de servir et alors nous seront bientôt libres.

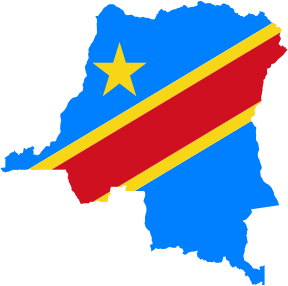

Noot Lucas Tessens: In werkelijkheid gaat het over één tand van Lumumba. Die had de schimmige opruimer Gerard Soete bijgehouden toen hij het lichaam van Lumumba in zuur oploste. De moord op Lumumba kan niet losgekoppeld worden van de secessie van Katanga, waar de Société Générale via de Union Minière de lakens uitdeelde. Maar daarover spreekt de liberaal De Croo natuurlijk niet.

Monsieur le Premier ministre de la République démocratique du Congo,

Excellences,

Chers membres de la famille de Son Excellence Monsieur Patrice Emery Lumumba,

et de Messieurs Maurice Mpolo et Joseph Okito,

Mesdames et Messieurs,

Permettez-moi de vous souhaiter, à toutes et à tous, la bienvenue à cette cérémonie. Une cérémonie de la plus haute importance pour les proches de feu Patrice Emery Lumumba, qui reçoivent aujourd'hui enfin la dépouille de leur père et grand-père.

Une cérémonie de la plus haute importance aussi pour le peuple congolais, qui aujourd'hui enfin prend réception de la dépouille du 1er Premier ministre de son pays.

Enfin, une cérémonie de la plus haute importance pour les relations entre nos deux pays, la République démocratique du Congo et le Royaume de Belgique, et entre nos deux peuples. Deux pays et deux populations qui peuvent, finalement, tourner une page de leur Histoire et entamer un nouveau chapitre.

Enfin : ce mot est sur toutes les lèvres ce matin. Et par enfin nous entendons « trop tard ». En réalité, beaucoup trop tard.

Car, non, il n'est pas normal que la dépouille de l'un des Pères fondateurs de la nation congolaise ait été conservée six décennies durant par les Belges.

Il n'est pas normal que la dépouille de l'un des Pères fondateurs de la nation congolaise ait été conservée durant six décennies dans des circonstances obscures, jamais vraiment élucidées, mais qui à la lumière de ce qui est connu ne font pas notre fierté.

Eindelijk: dat is het woord dat vanochtend op ieders lippen ligt. En met eindelijk bedoelen we "te laat". Veel te laat, eigenlijk.

Want nee, het is niet normaal dat het stoffelijk overschot van een van de grondleggers van de Congolese natie zes decennia lang door Belgen werd bewaard.

Het is niet normaal dat het stoffelijk overschot van een van de grondleggers van de Congolese natie zes decennia lang werd bewaard onder duistere omstandigheden, die nooit echt zijn opgehelderd, maar waar we in het licht van wat nu bekend is, niet trots op zijn.

At last: this word is on everyone's lips this morning. And by at last we mean "too late". In fact, much too late.

Because, no, it is not normal that Belgians held onto the remains of one of the Founding Fathers of the Congolese nation for six decades.

It is not normal that, for six decades, the remains of one of the Founding Fathers of the Congolese nation were kept in obscure circumstances, which were never really elucidated, but which in light of what is known do not make us proud.

La dépouille de Patrice Emery Lumumba n’est entrée en possession des autorités judiciaires de notre pays qu’en 2016. Et il a fallu attendre longtemps avant que cette dépouille ne soit remise à qui de droit : c’est à dire sa famille et son peuple. Pour enfin entamer un ultime voyage vers sa juste destination, Kinshasa, fière capitale de la République démocratique du Congo.

Non, il n'est pas normal qu’en l'an 2000 seulement, près de quarante ans après les terribles événements du 17 janvier 1961, une commission d'enquête parlementaire en Belgique se soit finalement penchée sur les circonstances précises dans lesquelles Patrice Emery Lumumba a été assassiné et sur l'éventuelle implication morale de militaires, fonctionnaires et politiciens belges dans cette affaire.

Ces dernières semaines, nous nous sommes entretenus avec le président de cette commission d'enquête parlementaire. Et j'ai lu, personnellement, les conclusions de cette enquête. Pour le transfert de Patrice Emery Lumumba au Katanga, les autorités congolaises de l'époque ont reçu l’aide de diplomates, de fonctionnaires et de militaires belges. La commission d'enquête parlementaire a donc conclu que le gouvernement belge faisait manifestement peu de cas de l'intégrité physique de Patrice Lumumba et qu'après son assassinat, ce même gouvernement a délibérément répandu des mensonges sur les circonstances de son décès. Plusieurs ministres du gouvernement belge de l'époque portent, en conséquence, une responsabilité morale quant aux circonstances qui ont conduit à ce meurtre. C'est une vérité douloureuse et désagréable. Mais elle doit être dite.

Les ministres, diplomates, fonctionnaires ou militaires belges n'avaient peut-être pas l'intention de faire assassiner Patrice Lumumba, aucune preuve n’a été trouvée pour l’attester. Mais ils auraient dû percevoir que son transfert au Katanga mettrait sa vie en péril. Ils auraient dû prévenir, ils auraient dû refuser toute aide pour le transfert de Patrice Lumumba vers le lieu où il a été exécuté. Ils ont choisi de ne pas voir. Ils ont choisi de ne pas agir.

Un homme a été assassiné pour ses convictions politiques, ses propos, son idéal. Pour le démocrate qui je suis c'est indéfendable, pour le libéral que je suis c’est inacceptable. Et pour l’humain que je suis c’est odieux.

Je tiens aussi à rendre un hommage appuyé aux deux autres personnes exécutées en même temps que Patrice Emery Lumumba : Maurice Mpolo et Joseph Okito.

Cette responsabilité morale du gouvernement belge, nous l’avons reconnue et je la répète à nouveau en ce jour officiel d’adieu de la Belgique à Patrice Emery Lumumba. Je souhaiterais ici, en présence de sa famille, présenter à mon tour les excuses du gouvernement belge pour la manière dont il a pesé )à l’époque sur la décision de mettre fin aux jours du 1er Premier ministre du pays.

Il y a vingt ans, le ministre des Affaires étrangères Louis Michel avait exprimé ses profonds regrets à la famille et au peuple congolais.

Des profonds regrets, le Roi Philippe en a lui aussi formulés, il y a deux ans, dans une lettre adressée au Président congolais Félix Tshisekedi. Et il les a réitérés en personne lors de sa visite officielle au Congo il y a quelques jours. De profonds regrets qui avaient cette fois pour objet, de manière plus globale, les actes de violence et de cruauté commis à l'époque de l'État indépendant du Congo. De profonds regrets pour les souffrances et les humiliations infligées pendant la période coloniale.

Une lettre courageuse et généreuse, comme l'a également reconnu le Président Tshisekedi. Une lettre nécessaire aussi. Car pour envisager notre futur ensemble, nous devons qualifier sans ambiguïté les passages sombres de notre passé commun. Il le faut si nous voulons tourner une page et entamer un nouveau chapitre de notre Histoire. Les jeunes, congolais comme belges, y aspirent.

La période coloniale, comme toute époque de l’Histoire, est soumise à interprétation et réinterprétation. Néanmoins, déjà à l’époque de l’État indépendant du Congo, de nombreuses voix se sont élevées pour dénoncer les abus et les violences. Ces voix ne se sont plus jamais tues.

Le Roi des Belges s’est exprimé en ces termes il y a quelques jours à Kinshasa devant le peuple congolais : Bien que de nombreux Belges se soient sincèrement investis, aimant profondément le Congo et ses habitants, le régime colonial comme tel était basé sur l’exploitation et la domination.

Ce régime était celui d’une relation inégale, en soi injustifiable, marqué par le paternalisme, les discriminations et le racisme. Il a donné lieu à des exactions et des humiliations.

Bien sûr, tout n'était pas mauvais. Bien sûr, il y a eu de bonnes choses. Bien sûr, de nombreux Belges se sont investis dans les colonies avec de nobles intentions. Mais ils ont, souvent inconsciemment mais parfois aussi sciemment, participé à l'asservissement d'un peuple, à l'occupation d'un pays, à l'exploitation de ressources naturelles et à la spoliation d’œuvres d’art. Il est grand temps, maintenant de remettre enfin la dépouille du premier Premier ministre du Congo à sa famille et à son peuple, d’expliquer clairement ce qu'a été la période coloniale et de restituer ce qui a été dérobé. Je me réjouis donc de l’adoption prochaine par le Parlement d’une loi permettant la restitution du patrimoine culturel, comme le propose ce gouvernement. Et je considérerai avec grand intérêt les conclusions de la commission parlementaire spéciale chargée d'examiner le passé colonial de la Belgique. Je ne veux pas préjuger de ces conclusions aujourd'hui. Mais je les attends avec impatience.

Comme l'esclavage, le modèle colonial était un système pernicieux en soi. Il s’agissait bien d’un modèle et d’un système et il ternit honteusement l’histoire de notre pays. Il nous faudra l’admettre sans ambages ni détour si nous voulons vivre une relation sincère et vraie avec les pays que nous avons occupés. Le Congo, le Rwanda, le Burundi.

Le gouvernement belge dénonce sans équivoque la colonisation en tant que système de gouvernance et d’idéologie, tant au Congo qu’au Burundi, au Rwanda et ailleurs. Ce système a mené à de graves violations des droits humains, des discriminations en tous genres, et une perception des Africains par certains Belges totalement inadéquate.

La perception inappropriée que certains ont développé à l’époque vis-à-vis des Africainsa laissé des traces jusqu’à ce jour, et se manifeste par les actes de racisme qui sont encore observés dans de trop nombreuses circonstances de la vie en Belgique. Je condamne vivement ce racisme. Il est plus que temps d’y mettre un terme définitif. Comme toutes les formes de discrimination, le racisme est non seulement dommageable à celui qui en est l’objet, mais également à celui qui en est l’auteur. Une société inclusive est une société plus riche, où chacun peut contribuer positivement au vivre ensemble et être reconnu pour sa contribution.

La communauté d’origine africaine en Belgique apporte une richesse inégalable à notre pays. Cet apport est parfois bien connu grâce à des secteurs très visibles, comme le sport et la culture, mais notre reconnaissance va également à toutes les Congolaises et Congolais, Africaines et Africains, devenus Belges ou non, qui apportent au quotidien leur pierre à l’édifice dans tellement d’autres domaines, souvent sans bénéficier d’une quelconque visibilité, comme tout autre citoyen dans notre pays. Nous pensons aussi que les Belges actifs en RDC ont cette même approche.

Ces Belges, ces Congolais et ces Congolaises, contribuent toutes et tous à ce lien indéfinissable et si étroit entre nos deux pays. Un lien qui va au-delà de l’amitié, et qui s’inscrit dans une approche à long terme, tournée vers l’avenir. Je me réjouis de cette nouvelle dynamique qui nous permet de nous regarder avec un respect et une franchise renouvelés, au bénéfice commun de nos populations.

Monsieur le Premier ministre,

Mesdames et Messieurs,

Nous commémorons aujourd'hui le terrible assassinat de Patrice Emery Lumumba. Nous nous inclinons devant sa mémoire. Le poids historique de cet homme pour son pays et son continent. Sa contribution majeure à la renaissance panafricaine.

Malgré la solennité de l’événement dont nous honorons aujourd’hui la mémoire, c’est aussi avec un message empreint d’espoir et de confiance en l’avenir que je souhaite clôturer cette cérémonie. Les jeunesses belge et congolaise sont pleines de ressources, de talent, et sont ouvertes aux autres. Elles continueront à porter ce lien qui unit nos deux peuples, dans les moments difficiles comme dans les moments de réjouissance.

Notre engagement pour les années à venir vis-à-vis de la RDC reste guidé par la ferme volonté de soutenir le processus de stabilisation et de démocratisation du pays, et l’attachement profond aux principes demandés par la population congolaise, comme le respect de l’État de droit et des principes démocratiques, l’avancement des droits humains, en particulier des femmes et des enfants, et la bonne gouvernance.

Vandaag herdenken we de gruwelijke moord op Patrice Emery Lumumba. We buigen het hoofd te zijner nagedachtenis. Voor het historische gewicht van deze man voor zijn land en zijn continent. Voor zijn enorme bijdrage aan de pan-Afrikaanse wedergeboorte.

Ondanks het plechtige karakter van het eerbetoon dat we hier vandaag brengen, wil ik deze plechtigheid ook graag afsluiten met een boodschap van hoop en vertrouwen voor de toekomst. De Belgische en Congolese jeugd loopt over van ideeën en talent, staat open voor anderen en zal deze band tussen onze twee volkeren blijven uitdragen, zowel in moeilijke tijden als in momenten van vreugde.

Ons engagement ten aanzien van de DRC in de komende jaren blijft ingegeven door onze vastbeslotenheid om het stabilisatie- en democratiseringsproces van het land te ondersteunen, en door onze sterke verbondenheid met de beginselen die het Congelese volk vraagt, zoals de eerbiediging van de rechtsstaat en de democratische beginselen, de bevordering van de mensenrechten, in het bijzonder die van vrouwen en kinderen, en een goed bestuur.

Today, we commemorate the terrible assassination of Patrice Emery Lumumba. We bow before his memory. The historical weight of this man who meant so much for his country and his continent. His major contribution to the pan-African renaissance.

Despite the solemnity of today’s event, I wish to close this ceremony with a message of hope and confidence in the future. Belgian and Congolese young people are resourceful, talented, and open. They will continue to carry this bond that unites our two peoples, in difficult times as well as in moments of joy.

Our commitment to the DRC for the coming years remains guided by the firm will to support the country's stabilization and democratization process, and a deep attachment to the desires of the Congolese people, such as respect for the rule of law and democratic principles, the advancement of human rights, especially of women and children, and good governance.

Nous posons aujourd’hui un acte de commémoration. Mais ce lundi, nous posons aussi un acte de renouvellement fort, de partenariat, entre Belges et Congolais.

Puisse ce jour nous projeter dans un avenir commun radieux.

Vandaag herdenken we. Maar we stellen ook een daad van sterke vernieuwing, van partnerschap, tussen de Belgen en de Congolezen.

Moge deze dag het begin zijn van een mooie gemeenschappelijke toekomst.

Today is a day of commemoration. But this Monday will also be a day of strong renewal and of partnership, between the Belgian and Congolese people.

May this day project us into a bright common future.

Avec la conquête de l'Algérie, qui débute en 1830, commence pour la France un siècle d'expansion sans précédent, qui va permettre au pays de se constituer un empire colonial couvrant une partie de l'Afrique et de l'Asie. Une expansion menée au nom du "progrès" et sous couvert de "missions civilisatrice". Mais en réalité, ces conquêtes territoriales ont été le résultat de campagnes militaires particulièrement violentes. Car, là où la France a tenté de planter son drapeau, elle a dû faire face à une résistance acharnée, de l'Algérie à l'Afrique noire, puis de l'Indochine au Maroc.

Partie 2 : Fragile apogée (1918-1931)

L'empire français, le deuxième au monde après celui des Britanniques, atteint en 1920 son apogée territorial. Avec le Liban, la Syrie, le Cameroun et le Togo, jamais le domaine colonial français n'avait été si vaste. Cependant, cet empire repose sur des bases fragiles. Au Maroc, comme en Syrie, plusieurs rebellions éclatent. La France entreprend des réformes pour associer les peuples colonisés aux destinées de leurs pays. Mais il est trop tard. Le lobby colonial sape les efforts des gouvernements de gauche, finalement incapables de changer le système.

Partie 3 : Prémices d'un effondrement (1931-1945)

Le 6 mai 1931, le président de la République, Gaston Doumergue, inaugure à Paris l'exposition coloniale. Le bois de Vincennes devient pour l'occasion une réplique miniature de l'empire colonial français, présentant ses richesses et ses curiosités. Tout à été fait pour donner l'image d'un monde parfait. Les millions de visiteurs sont loin d'imaginer que l'empire est en train de se diriger vers sa chute. D'Alger à Hanoï, les millions de sujets qui le composent remettent en cause la tutelle française. L'effondrement sera précipité par la Seconde Guerre mondiale.

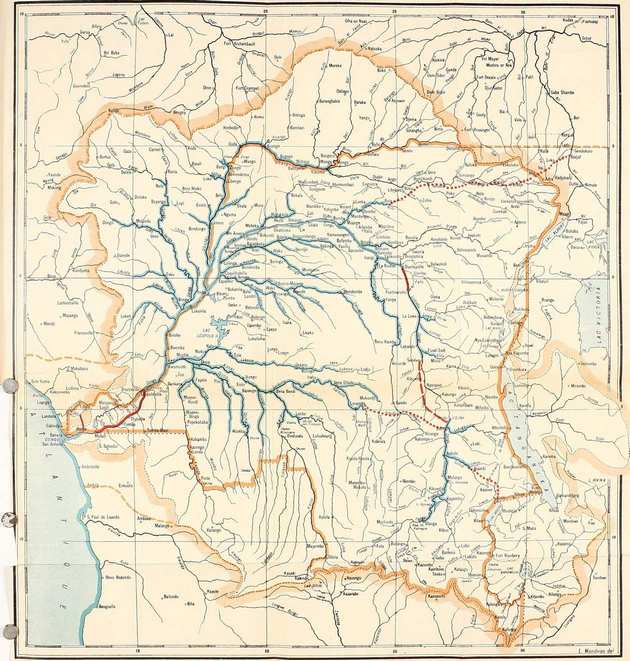

Chronologie des principaux événements historiques de la R.D.C.

Chronologie des principaux événements historiques de la R.D.C.Chronologie des principaux événements historiques de la R.D.C.

A. Les Royaumes (du 5è au 18è siècle)

Avant l’arrivée des Européens, la Région est occupée par des populations d’origine bantoue et des Pygmées.

Les bantous sont organisés en royaumes dont les principaux sont : le royaume Kongo (15è siècle), le Royaume Luba 15ème siècle, le royaume Lunda (16è siècle), Kazembe (18è), les royaumes Kuba, Yaka, Teke, et des chefferies indépendantes chez les Mangbetu, Azandé, Mongo…

B. Les Explorations (19è siècle)

Plusieurs siècles après la découverte de l'embouchure du Fleuve Congo en 1482 par Diego Cao, le 19è siècle a permis à d'autres explorateurs de révéler au monde extérieur certaines potentialités du bassin du Congo.

Il s'agit de l'Anglais Tuckey qui remonta en 1816 le fleuve Congo jusqu'aux chutes de Yelala et inaugura ainsi la période des explorations scientifiques du 19è siècle en Afrique Centrale. Ce fut ensuite le tour du journaliste et voyageur Anglo-américain Henry Morton Stanley qui retrouva à Ujiji sur la rive du Lac Tanganyika en Tanzanie, le missionnaire et voyageur Ecossais David Livingstone le 27 octobre 1871.

C'est ainsi que, attiré par les potentialités du Congo, le Roi des Belges Léopold II créa en octobre 1882, l'Association Internationale du Congo (AIC), avec laquelle il va lancer plusieurs expéditions d’exploration et finalement créer l’Etat Indépendant du Congo (EIC) ; qui fût consacré lors de la Conférence de Berlin, organisée en 1885, en tant que propriété personnelle du Roi Léopold II.

C. Période Coloniale (de 1908 au 29 juin 1960)

La période de la colonisation débute en 1908, avec l'annexion de l'EIC, à la Belgique, qui devient le Congo Belge, période qui dura jusqu’au 30 juin 1960.

La fin de la domination belge au Congo a été précipitée par plusieurs événements externes et internes, comme la participation des soldats de la Force publique aux conflits mondiaux de 14-18 et 40-45, l’alphabétisation de la population et l’avènement d’une classe moyenne congolaise, la création de nombreux partis politiques en 1958. Ensuite, l’éclatement de troubles et émeutes à caractère revendicatif en 1959,...), sans compter à l’extérieur l’influence de la Conférence panafricaine d'Accra en 1958, le discours de Brazzaville du Général de Gaulle, ...).

Sur le plan économique, la colonie a connu un essor certain, (création de plusieurs sociétés tant étatiques que privées dans les domaines du transport, de l'agriculture et des mines), période marquée aussi, par une crise de chômage à la veille de l’indépendance.

Sur le plan socioculturel, deux faits marquants méritent d'être signalés : la création en 1954 de l'Université Lovanium de Léopoldville, l'actuelle Université de Kinshasa, la première du Congo et de l'Afrique Centrale, ainsi que celle de l'Université Officielle du Congo à Elisabethville, l'actuelle Université de Lubumbashi.

Sur le plan religieux, les églises chrétiennes traditionnelles, à savoir l'Eglise Catholique et l'Eglise Protestante, rivalisent d'ardeur pour leur implantation maximale sur l'ensemble du Congo Belge.

Un autre événement mérite d'être signalé. Il s'agit de la naissance le 06 avril 1921 à Nkamba dans la Province du Bas-Congo du mouvement religieux de Simon Kimbangu, devenu en 1959 l'Eglise du Christ sur la Terre par le Prophète Simon Kimbangu (EJCSK).

D. Période Postcoloniale (du 30 juin 1960 à nos jours)

Cette période qui s'ouvre avec l'indépendance du Congo en 1960 se subdivise en trois sous-périodes :

• La Première République (de 1960 à 1965)

• La Deuxième République (de 1965 à 1997)

• La Troisième République (de 1997 à nos jours)

1. La Première République

L'indépendance du Congo a été obtenue le 30 juin 1960, après quatre années d'effervescence nationaliste. Le Congo belge accède à l'indépendance sous le nom de République du Congo, dite "Congo Kinshasa". Joseph Kasa-Vubu est le Premier Président de la République et Patrice Emery Lumumba le premier Premier Ministre.

Quelques temps après la proclamation de l'indépendance,le 30 juin 1960, le Katanga avec Moïse Tshombe fait sécession. Entre 1961 et 1965, plusieurs troubles éclatent, marqués notamment par l'assassinat de Patrice Emery Lumumba en 1961, l'intervention des Casques bleus de l'ONU (1961-1963), qui réduisent la sécession du Katanga, et celle des parachutistes belges (1964), pour mâter une rébellion d'obédience Lumumbiste.

2. La Deuxième République

Quelques dates méritent d'être retenues au cours de cette longue période de 32 ans.

Le 24 novembre 1965 : Accession de Mobutu Sese Seko à la Présidence de la République, à la suite d'un coup d'Etat.

En 1970: L'autoritarisme se renforce, avec l'instauration d'un régime de parti unique (Mouvement Populaire de la Révolution, M.P.R.).

En 1971 : La République du Congo prend le nom de Zaïre. De 1977 à 1978 : Mobutu fait appel à la France et au Maroc pour contenir de nouvelles rébellions (Kolwezi).

A partir de 1990 : Confronté à une opposition croissante et farouche, Mobutu est acculé à certaines concessions (ouverture au multipartisme, mise en place d'un pouvoir de transition) mais refuse la démocratisation complète des institutions.

En 1994 : La crise politique se double du problème de l'afflux massif des réfugiés rwandais.

3. La Troisième République

Cette période commence avec la fin de la guerre de Libération menée par Mzee Laurent Désiré KABILA.

En 1997: Les troupes rebelles, progressant d'Est à l'Ouest, prennent le contrôle du pays et contraignent Mobutu à abandonner le pouvoir.

Le 17 mai 1997: Laurent Désiré Kabila prend le pouvoir et rebaptise le Zaïre en République Démocratique du Congo.

Le 02 août 1998 : Début de l'agression de la République Démocratique du Congo par le Rwanda, l'Ouganda et le Burundi.

Le 16 janvier 2001 : Assassinat de Laurent Désiré Kabila.

Le 26 janvier 2001 : Avènement à la Magistrature Suprême de Joseph Kabila Kabange, qui devient Président de la République démocratique du Congo.

Le 02 avril 2003 : Adoption de l’Acte Final du Dialogue Inter-Congolais (DIC). Le Dialogue Inter-Congolais est une rencontre des protagonistes de la crise politique consécutive à la guerre qui a déchiré la RDC depuis 1998. Il constitue la matérialisation d’un des points clés de l’Accord de cessez-le -feu conclu à Lusaka, en Zambie, les 10 et 11 juillet 1999 entre les gouvernements de la RDC, de l’Ouganda et du Rwanda, et signé en août de la même année par les groupes des rebelles congolais soutenus par ces deux derniers pays.

En adoptant l’Acte Final, les parties au DIC acceptent comme exécutoires les instruments énumérés ci-dessous, convenus à l’issue des négociations politiques et devant régir la transition en RDC.

Il s’agit :

a) des trente-six résolutions sur le Programme d'action du gouvernement, dûment adoptées par la plénière du DIC;

b) de l’Accord Global et Inclusif sur la transition en RDC ainsi que du mémorandum additionnel sur l’armée et la sécurité, signés respectivement le 17 décembre 2002 et le 06 mars 2003 à Pretoria et endossés à Sun City le 1er avril 2003;

c) de la Constitution de la transition adoptée à Sun City en République Sud-africaine le 1er avril 2003.

Le 04 avril 2003 : Promulgation de la Constitution de la Transition par le Président Joseph Kabila.

Le 07 avril 2003 : Prestation de serment de Joseph Kabila, en qualité de Président de la République Démocratique du Congo pour la période de la transition.

Le 18 décembre 2005 : Référendum sur la nouvelle Constitution. Taux de participation: 84,31%.

Le 18 février 2006 : Promulgation de la Constitution de la 3ième République.

Le 31 juillet 2006 : premier tour des premières élections présidentielle et législative par suffrage universel.

Le 29 octobre 2006 : deuxième tour des élections présidentielle par chiffrage universelle.

Le 15 novembre 2006 : La Commission électorale indépendante proclame l'élection Joseph Kabila Kabange à la majorité absolue comme premier président de la 3ième République.

Le 06 décembre 2006 : prestation de serment du Président Joseph Kabila Kabange.

Le 29 octobre 2006 : installation du Parlement.

Le 29 octobre 2006 : installation du Sénat.

Le 29 octobre 2006 : installation de la Chambre Basse.

4. L’élection de Félix-Antoine Tshisekedi Tshilombo

A l’issue des élections présidentielles et législatives du 30 décembre 2018, Félix-Antoine Tshisekedi Tshilombo, fils de l’Ancien Premier ministre de la Transition et président de l’UDPS (Union pour la démocratie et le Progrès social), Etienne Tshisekedi wa Mulumba, est élu et devient le 5ème président de la République démocratique du Congo.

Cette élection marque pour la première fois dans l’histoire de la République démocratique du Congo, l’avènement pacifique d’un nouveau chef de l’Etat à la tête du pays.

(consulté 20210904)

Author: Monica Zanardo, University of Padova

Elsa Morante in other languages in: New Italian Books

The international success of the books of Elsa Morante (1912-1985) more or less mirrors her publishing success and popularity in Italy. After the lukewarm reception of Menzogna e sortilegio (1948), L’isola di Arturo (1957) was immediately successful, thanks also to its being awarded the prestigious Strega Prize, which also gave her greater visibility abroad. Her standing abroad was further enhanced after the publication of La Storia (1974), which was successful in terms of both popularity and sales, paving the way for her penetration of the European book market with her last novel, Aracoeli (1982). This success also contributed (though to a lesser extent) towards the rediscovery of her debut novel, which remains, however, Morante’s least translated book.

There were only two translations of Menzogna e sortilegio in the 1950s: the American edition published in 1951 and the German edition published in Zürich in 1952. This edition, translated by Hanneliese Hinderberger (who would later also translate La Storia in 1976), was subsequently published by the prestigious Suhrkamp Verlag (from 1981), with an afterword by Dominique Fernandez. There was a totally different reaction to her book in America, translated by Adrienne Foulke, with the editorial assistance of Andrew Chiappe, and published by Harcourt Brace following the intervention of William Weaver. Published under the title House of Liars, the book was a total failure. Morante was very unhappy with the translation, not just because of the many inaccuracies, but, above all, because of the major cuts imposed on her novel, which was abridged by almost 20%. After almost 70 years, a new translation is planned for The New York Review of Books. Menzogna e sortilegio is still today the least translated of Morante’s novels, even less translated than the collection of short stories Lo scialle andaluso. The novel was only rediscovered after L’isola di Arturo (the novel which brought her domestic fame and opened the door for her in many parts of Europe) was translated into French in 1967 (by Michel Arnaud, but with significant editing for Gallimard’s prestigious “Du monde entier” series) and Polish in 1968 (by Zofia Ernstowa, with the poetic inserts entrusted to Jerzy Kierst). Only after the author’s death was the book published in Danish (1988, translated by Jytte Lollesgaard), Hebrew (2000, translated by Miryam Shusṭ erman-Padovano) and Spanish (2012, translated by Ana Ciurans Ferrándiz, and republished in 2017 with a foreword by Juan Tallón). In 2019, the publishers Kastaniotis announced the imminent release of a translation into Greek, while translations are also underway into Dutch (as part of a larger publishing project to publish all of Morante’s novels being carried out by Wereldbibliotheek) and Macedonian. The reception of Morante’s works in the Balkans is rather different, however, as the first of her novels to be published in that region was, in fact, Menzogna e sortilegio (published in Yugoslavia, in 1972, in Serbo-Croatian, in its Cyrillic version by Miodrag Kujundzić and Ivanka Jovičić), with the rediscovery much later of Isola di Arturo and La Storia (both were published in 1987, in, respectively, Serbia, translated by Jasmina Livada, and Bosnia, translated by Razija Sarajilić), and, in 1989, of Lo Scialle andaluso (published by the Serbian publishing house Gradina and translated by Ana Srbinović and Elizabet Vasiljević).

The international success of L’isola di Arturo [Arturo’s Island] was more straightforward, with the book translated into fourteen languages within ten years of its publication in Italy. It was almost immediately available in Scandinavia, with the Finnish translation published in 1958 (Alli Holma) and the Swedish translation (Karin Alin) and Norwegian translation (Hans Braarving) in the following year. Between 1959 and 1960, the book was also translated into German (Susanne Hurni-Maehler, who, in 1985, also retranslated Lo scialle andaluso, the first German version of which, translated by Kurt Stoessel, was published in Switzerland in 1960), into English (by Isabel Quigly for Collins, with a new translation in 2019 by Ann Goldstein, the American translator of Elena Ferrante, who also has in the pipeline a new translation of La Storia [History: A Novel]), into Spanish (Eugenio Guasta in Argentina, with a version published in Catalan, translated by Joan Oliver, in 1965), into Polish (Barbara Sieroszewska) and Dutch (J.H. Klinkert-Pötters Vos). During the 1960s translations were also published in French (in 1963, Michel Arnaud, who subsequently also translated Menzogna e sortilegio in 1967 and La Storia in 1977, while her collection of short stories Lo scialle andaluso were translated by Mario Fusco), in Japanese (Teruo Ōkubo), in Hungarian (Éva Dankó), in Portuguese (Hermes Serrão in 1966, with a new translation by Loredana de Stauber Caprara and Regina Célia Silva published by the Brazilian publishing house Berlendis & Vertecchia in 2003), in Romanian (Constantin Ioncică – still Morante’s only book to be translated into Romanian, though there should soon be available a translation of La Storia), in Korean (1989), in Macedonian (2017, Nenad Trpovski), in Turkish (2007, Şadan Karadeniz, who ten years earlier had also translated Lo scialle andaluso) and in Albanian (2019, Shtëpia Botuese). Translations of L’isola di Arturo are currently underway into Georgian and Czech, while Morante’s first book to be published in Lithuanian will also be L’isola di Arturo (Alma Littera).

Morante’s first book to be published in Denmark was La Storia (1977), translated by Jytte Lollesgard, who went on to complete the translations of all Morante’s novels into Danish (L’isola di Arturo in 1984, and Menzogna e sortilegio and Aracoeli, both published in 1988), as well as her collection of short stories Le straordinarie avventure di Caterina (1989). In Slovenia, the international success of La Storia curiously led to L’Isola di Arturo being rediscovered (1976, translated by Cvetka Žužek-Granata), while Aracoeli (1993) and La Storia (2006), translated respectively by Srečko Fišer and Dean Rajčić, did not appear until after the author’s death.

Two translations of La Storia deserve a special mention: the American translation, because it was followed closely by Morante, and the Spanish translation, because of the controversy it caused. In America, the book was translated by William Weaver and published by the Franklin Library First Edition Society, with an invaluable preface by Morante, who negotiated with her literary agent Erich Linder for the punctuation in the book’s English title. The Spanish edition (1976, translated by Juan Moreno), on the other hand, was publicly criticised by the author, who accused the publishers Plaza y Janés of having censored her book, though an uncensored version of the book did not become available in Spanish (translated by Esther Benitez) until 1991. This translation was subsequently revised in 2008 by Flavia Cartoni, who also wrote a foreword to the novel.

Before the author’s death, La Storia was translated into twelve languages (in addition to the English and Spanish versions, there were also translations into French, German, Portuguese, Dutch, Finnish, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Japanese and Chinese), with the book translated into another five languages by the end of the 1990s (Serbian, Czech, Hebrew, Turkish and Greek). Other languages have been added during the last twenty years, including Russian, Hungarian and Macedonian, but also Persian and Slovak (with La Storia being Morante’s only work to be published in these two languages in, respectively, 2003 and 2010). Curiously, the book has not been translated into Polish, but it has been recently translated (or is being translated) into Albanian, Rumanian, and even Arabic and Georgian.

Despite Morante’s well-established international reputation, Aracoeli did not achieve the same international reach. In 1984, the novel was translated into English, Spanish, German, Norwegian and French (by Jean-Noël Schifano, with the novel awarded the prestigious Prix Médicis étrangers) and, in 1985, into Swedish. Not until after her death was the novel also published in Finnish (1987), Danish and Czech (1988, when the Czech translation of La Storia was also published) and Slovene (1993). Aracoeli was Morante’s first work to be translated into both Greek and Hebrew. In Israel the translation of Aracoeli (1989, Miryam Shusṭ erman-Padovano) was followed, in 1994, by Lo scialle andaluso (Orah Ayal) and, going backwards, Morante’s other novels (La Storia, translated in 1995 by ʻImanuʼel Beʼeri; L’isola di Arturo and Menzogna e sortilegio, both translated by Miryam Shusṭ erman-Padovano and published in, respectively, 1997 and 2000). In Greece, the translation of Aracoeli (1989) paved the way for a very positive reception of Morante’s work and, in addition to the translations of her major novels and collections of short stories, there is one of the very rare translations of Il mondo salvato dai ragazzini (1996) and of the even less translated Lettere ad Antonio (published posthumously in Italy, edited by Alba Andreini, with title Diario 1938), which, besides Greek, can only be read in German and French.

Less successful, but nevertheless satisfactory, was the publication internationally of her collection of short stories Lo scialle andaluso (which have still not been translated into English), which were almost immediately translated into French and German, and then, during the 1980s, into Turkish, Estonian and Serbian. They can now also be read in Hebrew, Dutch, Spanish, Japanese, Albanian and Russian (the stories from Lo scialle andaluso and La Storia are Morante’s only works to be translated into Russian). They will soon be published in Portuguese, too. There are fewer translations of her short stories that were published posthumously. Racconti dimenticati have been translated into German, Greek, French and Dutch (in Dutch these short stories were published together with those from Lo scialle andaluso), with a Hebrew version currently underway; while Aneddoti infantili have only been translated into French (2015, Claire Pellissier). The collection of short stories for children, Straordinarie avventure di Caterina, have been fairly successful, however. They were translated almost immediately into Japanese and Hungarian, and, after the author’s death and during the 1990s, into French, Swedish, Danish, Spanish, Norwegian and German.

There are very few translations, however, of Alibi, the short collection of poems published by Longanesi in 1958. It was translated into French in 1999 (Jean-Noël Schifano, in a bilingual edition) and into Dutch in 2012 (Jan van der Haar, with the original and translation on opposite pages and a postword by Gandolfo Cascio, who was awarded the Morante Prize in 2016 for promoting Morante’s work in the Netherlands). Some individual poems have been translated, usually in magazines, as in the case of the poem that gives its name to the collection, which was translated into Polish in 1989 by Konstanty Jeleński, a friend of the author. Equally unsuccessful, partly because of the unusual form of the poems and their linguistic and conceptual complexity, and partly because they did not appeal to readers, is Il mondo salvato dai ragazzini (1968), which can only be read in French, Greek and English.

As for her literary and political writings, scant attention has been paid to Piccolo manifesto dei Comunisti (translated solely into French) and her sundry writings collected by Cesare Garboli in Pro o contro la bomba atomica e altri scritti, which can be read in German, French, Swedish, Spanish and Polish, and are currently being translated in Brazil. Her essay Sul Romanzo has been translated into Swedish, while her writings on Beato Angelico had already been translated in the 1970s.

While Elsa Morante’s minor works and poetry have a limited audience internationally, her novels, after she was awarded the prestigious Strega Prize and thanks also to the hard work of her literary agent Erich Linder, have received the attention they deserve (above all in France, Germany and Scandinavia, where they continue to be of interest). Moreover, following the author’s death, there have been publication projects in countries such as Israel, Greece and the Netherlands, to publish her complete works, some of which are nearing completion. The translation licences, some of which have been granted quite recently, confirm the continuing popularity of one of the most representative – and most represented – voices of twentieth-century Italian literature, with at least one of her works being translated into more than thirty language and whose books are distributed in all five continents.

Voor het hoogtepunt zorgde Amanda Gorman (22) die haar gedicht - 'The Hill We Climb' - voordroeg. Zij toonde Amerika van zijn beste kant. Natuurlijk kan een gedicht de wereld niet veranderen, het kan wel het begin zijn van een nieuw inzicht, 'a new dawn'. En wellicht wordt het beleid van Joe Biden later wel afgerekend op deze ritmische woorden.

Voor het hoogtepunt zorgde Amanda Gorman (22) die haar gedicht - 'The Hill We Climb' - voordroeg. Zij toonde Amerika van zijn beste kant. Natuurlijk kan een gedicht de wereld niet veranderen, het kan wel het begin zijn van een nieuw inzicht, 'a new dawn'. En wellicht wordt het beleid van Joe Biden later wel afgerekend op deze ritmische woorden.

When day comes, we ask ourselves where can we find light in this never-ending shade?

The loss we carry, a sea we must wade.

We’ve braved the belly of the beast.

We’ve learned that quiet isn’t always peace,

and the norms and notions of what “just” is isn’t always justice.

And yet, the dawn is ours before we knew it.

Somehow we do it.

Somehow we’ve weathered and witnessed a nation that isn’t broken,

but simply unfinished.

We, the successors of a country and a time where a skinny black girl descended from slaves and raised by a single mother can dream of becoming president, only to find herself reciting for one.

And yes, we are far from polished, far from pristine,

but that doesn’t mean we are striving to form a union that is perfect.

We are striving to forge our union with purpose.

To compose a country committed to all cultures, colors, characters, and conditions of man.

And so we lift our gazes not to what stands between us, but what stands before us.

We close the divide because we know, to put our future first, we must first put our differences aside.

We lay down our arms so we can reach out our arms to one another.

We seek harm to none and harmony for all.

Let the globe, if nothing else, say this is true:

That even as we grieved, we grew.

That even as we hurt, we hoped.

That even as we tired, we tried.

That we’ll forever be tied together, victorious.

Not because we will never again know defeat, but because we will never again sow division.

Scripture tells us to envision that everyone shall sit under their own vine and fig tree and no one shall make them afraid.

If we’re to live up to our own time, then victory won’t lie in the blade, but in all the bridges we’ve made.

That is the promise to glade, the hill we climb, if only we dare it.

It’s because being American is more than a pride we inherit.

It’s the past we step into and how we repair it.

We’ve seen a force that would shatter our nation rather than share it.

Would destroy our country if it meant delaying democracy.

This effort very nearly succeeded.

But while democracy can be periodically delayed,

it can never be permanently defeated.

In this truth, in this faith, we trust,

for while we have our eyes on the future, history has its eyes on us.

This is the era of just redemption.

We feared it at its inception.

We did not feel prepared to be the heirs of such a terrifying hour,

but within it, we found the power to author a new chapter, to offer hope and laughter to ourselves.

So while once we asked, ‘How could we possibly prevail over catastrophy?’ now we assert, ‘How could catastrophy possibly prevail over us?’

We will not march back to what was, but move to what shall be:

A country that is bruised but whole, benevolent but bold, fierce and free.

We will not be turned around or interrupted by intimidation because we know our inaction and inertia will be the inheritance of the next generation.

Our blunders become their burdens.

But one thing is certain:

If we merge mercy with might, and might with right, then love becomes our legacy and change, our children’s birthright.

So let us leave behind a country better than the one we were left.

With every breath from my bronze-pounded chest, we will raise this wounded world into a wondrous one.

We will rise from the golden hills of the west.

We will rise from the wind-swept north-east where our forefathers first realized revolution.

We will rise from the lake-rimmed cities of the midwestern states.

We will rise from the sun-baked south.

We will rebuild, reconcile, and recover.

In every known nook of our nation, in every corner called our country,

our people, diverse and beautiful, will emerge, battered and beautiful.

When day comes, we step out of the shade, aflame and unafraid.

The new dawn blooms as we free it.

For there is always light,

if only we’re brave enough to see it.

If only we’re brave enough to be it.

herlees de speech die Martin Luther King gaf op 28 augustus 1963: I have a dream

Persbericht 17 maart 2020

Persbericht 17 maart 2020Coronavirus: Versterkte maatregelen

Tijdens de Nationale Veiligheidsraad, uitgebreid met de ministers-presidenten, van dinsdag 17 maart is besloten tot aanvullende maatregelen. Enerzijds zijn deze maatregelen gebaseerd op de evolutie van de verspreiding van Covid-19 in België. Anderzijds vloeien ze voort uit de nieuwe conclusies en aanbevelingen van CELEVAL (Evaluatiecel) die gisteren en vanochtend zijn geformuleerd.

De genomen beslissingen zijn opnieuw het resultaat van een sterke samenwerking tussen de bevoegdheidsniveaus, die essentieel is voor het goede beheer van de huidige crisis. Iedereen aan tafel is zich ervan bewust hoe moeilijk de hieronder opgesomde maatregelen zijn en in welke mate ze een impact zullen hebben op het dagelijkse leven van iedereen. Maar de ernst van de situatie en de bescherming van de volksgezondheid maken deze opofferingen noodzakelijk.

De autoriteiten rekenen op het plichtsbesef van elke Belg en vertrouwen erop dat deze beslissingen, die genomen werden om hem, maar ook zijn naasten en dierbaren te beschermen, ten volle worden gerespecteerd. Alleen de persoonlijke inzet van iedereen zal ervoor zorgen dat deze maatregelen een reële impact hebben op de situatie.

De onderstaande maatregelen treden in werking op woensdag 18 maart op de middag en worden gehandhaafd tot en met 5 april. De situatie zal nog steeds dagelijks worden geëvalueerd en zal kunnen worden aangepast naargelang de evolutie ervan.

(1) Burgers zijn verplicht thuis te blijven om zoveel mogelijk contact buiten hun gezin te vermijden:

Behalve om naar het werk te gaan;

Behalve voor essentiële verplaatsingen (naar de dokter, voedingswinkels, het postkantoor, de bank, de apotheek, om te tanken of om mensen in nood te helpen);

Lichaamsbeweging in de buitenlucht is toegestaan en zelfs aanbevolen. Dit kan met gezinsleden die onder hetzelfde dak wonen en met een vriend. Uitstapjes met gezinsleden die onder hetzelfde dak wonen zijn toegestaan. Het is belangrijk om een redelijke afstand te bewaren.

Samenscholingen zijn niet toegestaan.

(2) Bedrijven zijn - ongeacht hun omvang - verplicht om telewerk te organiseren voor elke functie waar dit mogelijk is, zonder uitzondering.

Voor degenen voor wie deze organisatie niet mogelijk is, zal de social distancing strikt worden gerespecteerd. Deze regel geldt zowel voor de uitoefening van het werk als voor het door de werkgever georganiseerde vervoer. Als het voor bedrijven onmogelijk is om aan deze verplichtingen te voldoen, moeten zij hun deuren sluiten.

Indien de autoriteiten vaststellen dat de social distancing-maatregelen niet worden nageleefd, wordt de onderneming in eerste instantie een zware boete opgelegd; in geval van niet-naleving na de sanctie zal de onderneming moeten sluiten.

Deze bepalingen zijn niet van toepassing op de cruciale sectoren en essentiële diensten. Die zullen er echter voor moeten zorgen dat de regels inzake social distancing in de mate van het mogelijke in acht worden genomen.

(3) Niet-essentiële winkels en handelszaken blijven gesloten, met uitzondering van voedingswinkels, apotheken, dierenvoedingswinkels en krantenwinkels.

Daarnaast zal de toegang tot supermarkten worden gereguleerd, met een beperking tot een specifiek aantal klanten (1 persoon per 10m² en een maximale aanwezigheid van 30 minuten).

Cafés moeten hun terrasmeubilair verplicht binnenzetten.

Nachtwinkels mogen tot 22 uur open blijven, met inachtneming van de instructies op het vlak van social distancing.

Wat kappers betreft, wordt per kapsalon één klant tegelijk toegelaten.

(4) Het openbaar vervoer moet zodanig worden georganiseerd dat social distancing kan worden gegarandeerd.

(5) Reizen buiten België die niet als noodzakelijk worden beschouwd, worden tot en met 5 april verboden.

(6) Markten in de open lucht worden gesloten. Voedingskramen zijn alleen toegelaten op plaatsen waar ze onmisbaar zijn.

Tot slot, we kunnen het niet genoeg benadrukken, blijven de basishygiënemaatregelen van toepassing.