Search

Search our 7.940 News Items

CATEGORIES

We found 157 books in our category 'RELIGION'

We found 26 news items

We found 157 books

London

Zed Books

2002

INT

condition: Very good/Très bel état/Sehr gut/Zeer goed

book number: 202404121519

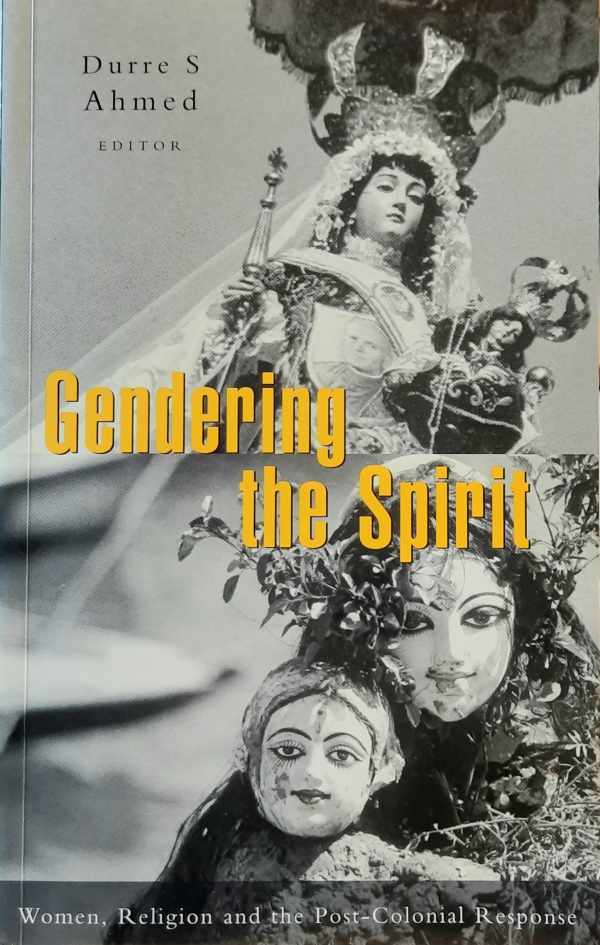

Gendering the Spirit - Women, Religion and the Post-Colonial Response

Paperback, in-8, 264 pp.

Religion remains a powerful reality for countless human beings across a range of cultures and systems of beliefs. This text is about the devotional subcultures created by women. Its authors draw their evidence and inspiration from Hindu, Buddhist, Islamist and Christian traditions. Here we find women as healers, goddesses, saints, gurus, nuns and heretics - all sharing a defiance of orthodoxy and fundamentalist oppressions of women

Religion remains a powerful reality for countless human beings across a range of cultures and systems of beliefs. This text is about the devotional subcultures created by women. Its authors draw their evidence and inspiration from Hindu, Buddhist, Islamist and Christian traditions. Here we find women as healers, goddesses, saints, gurus, nuns and heretics - all sharing a defiance of orthodoxy and fundamentalist oppressions of women

AHMED Durre@ wikipedia

€ 15.0

De Koran

Pb, xx + 879 pp., register. Ingeleid door Dr J.J.G. Jansen. Deze vertaling is bedoeld voor niet-moslims. In de noten worden parallellen getrokken met de Bijbel (OT).

Allah@ wikipedia

€ 15.0

De tombe van God. Het lichaam van Jezus en de ontknoping van een 2000 jaar oud mysterie

4de druk. Paperback, in-8, 463 pp., illustraties, bibliografische noten, bibliografie, index/register.

ANDREWS Richard, SCHELLENBERGER Paul@ wikipedia

€ 15.0

Amsterdam

Bezige Bij

2015

INT

condition: Very good/Très bel état/Sehr gut/Zeer goed

book number: 202202191804

In naam van God - Religie en geweld (vert. van Fields of Blood: Religion and the History of Violence - 2014)

Dikke pb met flappen, grote in-8, 639 pp., bibliografische noten, bibliografie, index.

Breed historisch overzicht van de relatie tussen religie en geweld, vanaf de prehistorie tot heden.

KA (1944)

Noot LT: KA schrijft op p. 412 over Atatürk: 'Maar hij was in feite een dictator die een grote haat koesterde tegen de islam.' En verder: 'Toen Atatürk aan de macht kwam, voltooide hij deze etnische zuivering.'

Die stellingen lijken ons te ongenuanceerd.

De paragrafen over het ontstaan van het Moslimbroederschap (416-417) door Hassan Banna (1906-1949) zijn lezenswaardig. Het Moslimbroederschap was anti-intellectualistisch, autoritair en had een zwart kantje: 'het moordgenootschap', o.l.v. Answar Sadat.

Breed historisch overzicht van de relatie tussen religie en geweld, vanaf de prehistorie tot heden.

KA (1944)

Noot LT: KA schrijft op p. 412 over Atatürk: 'Maar hij was in feite een dictator die een grote haat koesterde tegen de islam.' En verder: 'Toen Atatürk aan de macht kwam, voltooide hij deze etnische zuivering.'

Die stellingen lijken ons te ongenuanceerd.

De paragrafen over het ontstaan van het Moslimbroederschap (416-417) door Hassan Banna (1906-1949) zijn lezenswaardig. Het Moslimbroederschap was anti-intellectualistisch, autoritair en had een zwart kantje: 'het moordgenootschap', o.l.v. Answar Sadat.

ARMSTRONG Karen@ wikipedia

€ 15.0

Amsterdam

Flamingo

2000

INT

condition: Good

book number: 201405221532

Een geschiedenis van God. Vierduizend jaar jodendom, christendom en islam (vert. van A history of God)

17de druk. Paperback 511 pp. Vertaald door Ronald Cohen. Historische kaartjes, verklarende woordenlijst, bibliografische noten, bibliografie, register/index. 16de druk. Dit is de geschiedenis van God zoals de mens in hem geloofd heeft. Een controversieel en geniaal boek.

ARMSTRONG Karen@ wikipedia

€ 15.0

Amsterdam

Anthos

1996

INT

condition: Very good/Très bel état/Sehr gut/Zeer goed

book number: 201602122145

Mohammed - Een westerse poging tot begrip van de islam (vertaling van Muhammad

Paperback, in-8, 319 pp., geen illustraties, bibliografische noten, bibliografie, index/register.

Paperback, in-8, 319 pp., geen illustraties, bibliografische noten, bibliografie, index/register. Armstrong is de auteur van de bestseller 'Een geschiedenis van God' .

ARMSTRONG Karen@ wikipedia

€ 15.0

De strijd om God. Een geschiedenis van het fundamentalisme.

Thick pb, in-8, 493 pp., met verklarende woordenlijst, bibliografie, index.

ARMSTRONG Karen@ wikipedia

€ 10.0

Baarn

Tirion

1991

ISR

condition: Good, stofwikkel ontbreekt

book number: 34513

De Dode-Zeerollen en de verzwegen waarheid

Hardcover, linnen, gebonden, 8vo, 256 pp., index, bibliografie, geïllustreerd

BAIGENT Michael, LEIGH Richard@ wikipedia

€ 10.0

Utrecht/Antwerpen

Het Spectrum

1967

INT

condition: Very good/Très bel état/Sehr gut/Zeer goed

book number: 99990107

Het veldwerk van Teilhard de Chardin

Gebrocheerd, 198 pp. uit de Bibliotheek Teilhard de Chardin. Met ZW-illustraties en enkele foto's. Citaat uit de slotbeschouwingen: "In deze oneindig grote en ogenschijnlijk zinloze wereld is de moderne mens eenzaam en geestelijk ontredderd.Voor hem betekenen Teilhards ideeën over de evolutie een vleugje hoop en een antwoord op de behoeften van onze tijd." (p. 198) In de optimistische filosofie staat de evolutie naar 'het PUNT OMEGA' centraal, een collectiviteit die tot eenstemmigheid komt, een soort bovenbewustzijn.

BARBOUR George B. @ wikipedia

€ 10.0

Paris

Hachette

1978

FRA

condition: good, bon état

book number: 202403051631

Priez pour nous à Compostelle

Broché, in-8, 348 pp.

BARRET, GURGAND@ wikipedia

€ 10.0

Doetinchem

Stichting Rapportage

1990

INT

condition: Ex-library. Usual stamps. Very good

book number: 201705271739

Geschiedenis van het protestantisme (vert. van Histoire du Protestantisme - 1990)

Pb, in-8, 140 pp., chronologie, bibliografie, index. Voorwoord Prof. Boendermaker. Vertaald uit het Frans.

Baubérot, prof aan de Sorbonne en directeur van de sectie religieuze wetenschappen.

In 2017 is het 500 jaar geleden dat Luther zijn 95 stellingen lanceerde.

Baubérot, prof aan de Sorbonne en directeur van de sectie religieuze wetenschappen.

In 2017 is het 500 jaar geleden dat Luther zijn 95 stellingen lanceerde.

BAUBÉROT Jean@ wikipedia

€ 15.0

Paris

Lauzeray

1978

FRA

condition: couverture défraîchie, sinon en bon état

book number: 19780171

Symbolisme maçonique traditionnel (3ième édition remaniée et augmentée)

Broché, in-8, 466 pp., illustrations en NB, chronologie de la maçonnerie française 1275-1964, bibliographie. Bayard (1920-2008) est un docteur ès lettres, ingénieur, historien et auteur français.

BAYARD Jean-Pierre@ wikipedia

€ 25.0

London

Modern Library

1988

GBR

condition: Very good/Très bel état/Sehr gut/Zeer goed

book number: 202404121523

A modern library BBC Audiobook (12 cassettes). The New Testament. The Revised Version

Box with 12 cassettes

U moet wel over een cassettespeler beschikken.

U moet wel over een cassettespeler beschikken.

BBC@ wikipedia

€ 10.0

Utrecht

Spectrum i.s.m. de St. Willibrordvereniging en de Katholieke Actie.

1954

VAT

condition: Goed/Bon état/Good/Gut

book number: 19540002

Pius XII. Bewaker van de vrede

1954, 2de druk. Vertaald door E. Herkes.

BEIEREN Prins Constantijn van @ wikipedia

€ 10.0

Amsterdam

Wereldbibliotheek

1990

ITA

condition: Cover unfresh, inside good.

book number: 19850234

Sancta Anorexia. Vrouwelijke wegen naar heiligheid. Italië 1200-1800.

Pb, in-8, 300 pp., illustaties in ZW, index. Volgens deze studie zou anorexia te maken hebben met een zeer sterke hang naar identiteit en zelfbewustzijn.

BELL Rudolph M. @ wikipedia

€ 20.0

Paris

Centurion

1991

GTM

condition: Very good

book number: 201711181651

Les rendez-vous de Saint-Domingue (1492-1992)

Paperback, in-8, 365 pp. Livre en préparation de la réunion à Saint-Domingue en 1992 de l'assemblée des évêques latino-américains, autour du pape Jean-Paul II.

Sur l'Amerique Latine: "Il n'est donc pas étonnant que les pays qui montrent les indices les plus élevés de concentration du revenu (indice de Gini) présentent aussi les indices les plus élevés de pauvreté et d'indigence. C'est le cas du Guatemala (67,1 % de la population est pauvre), du Pérou (51 %) et du Brésil (40,1 %)." (247)

A relire: Evangile et idéologies (268 s.)

Sur l'Amerique Latine: "Il n'est donc pas étonnant que les pays qui montrent les indices les plus élevés de concentration du revenu (indice de Gini) présentent aussi les indices les plus élevés de pauvreté et d'indigence. C'est le cas du Guatemala (67,1 % de la population est pauvre), du Pérou (51 %) et du Brésil (40,1 %)." (247)

A relire: Evangile et idéologies (268 s.)

BERTEN Ignace, LUNEAU René (sous la direction de -)@ wikipedia

€ 15.0

Amsterdam

Prometheus

1995

INT

condition: Very good/Très bel état/Sehr gut/Zeer goed

book number: 202311291829

Het Kerkelijk Jaar. Christelijke feestdagen vroeger en nu (vertaling van Das Kirchenjahr - 1987)

Paperback, in-8, 279 pp., bibliografie, index/register.

Uit het Duits vertaald door Maarten van der Marel.

Vele betekenissen zijn verloren gegaan en dat is jammer. Want de structuur van onze westerse maatschappij wordt door het christelijke kalenderjaar bepaald.

Uit het Duits vertaald door Maarten van der Marel.

Vele betekenissen zijn verloren gegaan en dat is jammer. Want de structuur van onze westerse maatschappij wordt door het christelijke kalenderjaar bepaald.

BIERITZ Karl-Heinrich@ wikipedia

€ 10.0

London

BBC

1987

ISR

condition: Very Good/No Jacket.

book number: 19870018

The Cross and the Crescent : A History of the Crusades

Paperback, 8vo, Black pictorial wraps with white and red lettering on front and spine.

BILLINGS Malcolm@ wikipedia

€ 20.0

Averbode

Altiora

1986

BRA

condition: Very good

book number: 201712161710

Wat is theologie van de bevrijding?

Pb, in-8, 120 pp.

BOFF Leonardo, BOFF Clodovis@ wikipedia

€ 15.0

Paris

Nouveau Monde Editions/Fondation Napoléon

2002

FRA, BEL

condition: As new/comme neuf/wie neu/als nieuw.

book number: 202102061741

Les élites religieuses à l'époque de Napoléon - Dictionnaire des évêques et vicaires généraux du Premier Empire

Broché, in-8, 313 pp., illustrations, notes bibliographiques, bibliographie, index.

BOUDON Jacques-Olivier@ wikipedia

€ 15.0

We found 26 news items

Statement to the media by the United Nations Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent, on the conclusion of its official visit to Belgium, 4-11 February 2019

ID: 201902111471

Brussels, 11 February 2019

The Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent thanks the Government of Belgium for its invitation to visit the country from 4 to 11 February 2019, and for its cooperation. In particular, we thank the Federal Public Service Foreign Affairs, Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation. We also thank the OHCHR Regional Office for Europe for their support to the visit.

The views expressed in this statement are of a preliminary nature and our final findings and recommendations will be presented in our mission report to the United Nations Human Rights Council in September 2019.

During the visit, the Working Group assessed the human rights situation of people of African descent living in Belgium, and gathered information on the forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, Afrophobia and related intolerance they face. The Working Group studied the official measures taken and mechanisms to prevent systemic racial discrimination and to protect victims of racism, as well as responses to multiple forms of discrimination.

As part of its fact-finding mission, the Working Group visited Brussels, Antwerp, Liege, Namur and Charleroi. It met with senior officials of the Belgian Government at the federal, regional, community and local levels, the legislature, law enforcement, national human rights institutions, OHCHR Regional Office, non-governmental organizations, as well as communities and individuals working to promote the rights of people of African descent in Belgium. The Working Group toured the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA). It also visited the St. Gilles prison in Brussels.

We thank the many people of African descent and others, representing civil society organizations, human rights defenders, women’s organizations, lawyers, and academics whom we met during the visit. The contributions of those working to promote and protect the rights of people of African descent, creating initiatives, and proposing strategies to address structural racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, Afrophobia and related intolerance are invaluable.

The protection of human rights and the prohibition of racial discrimination is enshrined in Articles 10-11 in the Belgian Constitution. Belgium’s national anti-racism legislation is the 1981 anti-discrimination law, updated in 2007. Regions and communities also have anti-discrimination legislation.

We welcome the initiatives undertaken by Government at the federal, regional and community levels to combat racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance. We encourage efforts to raise awareness and support civil society including through the provision of funding.

The Working Group recognizes the important work of the Inter-Federal Centre for Equal Opportunities (Unia) in the protection and promotion of human rights, and in documenting racism and inequality at the federal and regional levels. Unia also provides recommendations on participation, tolerance, discrimination and diversity as well as their implementation in Belgium. Its diversity barometers provide important information on the human rights situation of people of African descent.

Throughout our visit we appreciated the willingness of public officials to discuss how public and private institutions may sustain racial disparities. We welcome the national network of expertise on crime against people, a robust infrastructure for combatting hate crime. In Brussels, Antwerp, Liege, Namur and Charleroi, the Working Group received information about social integration and intercultural efforts for new arrivals, including referral to language tuition. In Liege, we welcome the commitment enshrined in the Charter, Liege Against Racism.

The Working Group also welcomes the civil society initiatives to promote the International Decade for people of African descent in Belgium.

One of the ways the African diaspora in Belgium is expressing its voice is through cultural events such as the Congolisation festival to highlight the contribution of Congolese artists to the Belgian cultural landscape and make people begin to appreciate and reflect on the diaspora’s artistic heritage.

Despite the positive measures referred to above, the Working Group is concerned about the human rights situation of people of African descent in Belgium who experience racism and racial discrimination.

There is clear evidence that racial discrimination is endemic in institutions in Belgium. Civil society reported common manifestations of racial discrimination, xenophobia, Afrophobia and related intolerance faced by people of African descent. The root causes of present day human rights violations lie in the lack of recognition of the true scope of violence and injustice of colonisation. As a result, public discourse does not reflect a nuanced understanding of how institutions may drive systemic exclusion from education, employment, and opportunity. The Working Group concludes that inequalities are deeply entrenched because of structural barriers that intersect and reinforce each other. Credible efforts to counter racism require first overcoming these hurdles.

We note with concern the public monuments and memorials that are dedicated to King Leopold II and Force Publique officers, given their complicity in atrocities in Africa. The Working Group is of the view that closing the dark chapter in history, and reconciliation and healing, requires that Belgians should finally confront, and acknowledge, King Leopold II’s and Belgium’s role in colonization and its long-term impact on Belgium and Africa.

The most visible postcolonial discourse in a Belgian public institution takes place within the recently reopened Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA), which is both a research and a cultural institution. RMCA has sought to review its approach to include critical, postcolonial analysis- a marked shift for an institution originally charged with promulgating colonial propaganda. The Working Group is of the view that the reorganization of the museum has not gone far enough. For those communities that do engage in vibrant postcolonial discourse, i.e., civil society and activists, the reorganization falls short of its goal of providing adequate context and critical analysis. The Working Group notes the importance of removing all colonial propaganda and accurately presenting the atrocities of Belgium’s colonial past. The RMCA admits that decolonization is a process and reports its intention to evolve towards sharing power with people and institutions of African descent.

The Working Group welcomes this process of decolonization, as even recent cultural production in Belgium reflects enduring legacies of the colonial past. For example, a 2002 exhibit of eight Africans in a private zoo in Belgium (Cameroonians brought to Belgium without visas) recalls Belgium’s notorious “human zoos” between 1897 and 1958.

Reportedly, between 1959 and 1962, thousands of children born to white fathers and African mothers in Belgian-ruled Congo, Rwanda and Burundi were abducted and sent to Belgium for adoption. The Working Group notes with approval that the 2016 appeal by Metis de Belgique for state recognition was met with an apology from the Catholic Church the following year and a 2018 parliamentary resolution on la ségrégation subie par les métis issus de la colonisation belge en Afrique. The Working Group commends the provision of funding for data gathering, research and accountability within this framework.

Belgium often refers to intercultural, rather than multicultural, goals with the idea of preserving individual cultural heritage and practices while coexisting in peace and prosperity with respect and regard for the intersection and interaction of diverse cultures. This diversity includes citizens, migrants, people of first, second, and third generation residency, highly educated people, and groups that have contributed enormously to the modern Belgian state. Interculturality requires reciprocity, rejection of harmful cultural stereotype, and valuing of all cultures, including those of people of African descent.

The Working Group notes with concern the absence of disaggregated data based on ethnicity or race. Disaggregated data is required for ensuring the recognition of people of African descent and overcoming historical “social invisibility”. Without such data, it is impossible to ensure that Belgium’s reported commitments to equality are actually realized. Some anti-discrimination bodies have found proxy data (relating to parental origin) that have informed equality and anti-racism analyses; additional data relating to regroupement famille (and other data) may also extend these analyses to Belgian citizens of African descent.

Belgium has a complex political system. This must not impede fulfilment of its obligations to combat racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance. The lack of an A-Status National Human Rights Institution and a National Action Plan to combat racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, Afrophobia and related intolerance must be addressed. Belgium should engage actively in partnership with people of African descent, particularly experts in navigating these complexities, to promote equality and to diminish entrenched racial disparity.

The Working Group notes both civil society and law enforcement acknowledge the prevalence of racial profiling in policing. Reportedly, counter-terrorism policies have contributed to an increase in racial profiling by law enforcement. The federal police recognized the concern with racial profiling and offered additional information about a pilot study in Mechelen to document all stops and searches (including a narrative basis for the stop) over a two-year period. However, it is unclear how this may effectively target racial profiling as the race of the community members stopped by the police are not included among the data captured by the stop report.

The Working Group visited St. Gilles Prison in Brussels. The Working Group found the prison dilapidated and overcrowded. It is scheduled for relocation in 2022. Frequent strikes by prison personnel dramatically impact the conditions of confinement for incarcerated people housed there, including suspensions of visitation, showers, phone access, recreation, and prolonged lockdowns. Another concern raised by the detainees was the lack of attention to their requests for medical attention. There were also individual reports of racist behaviour by some of the guards, and the administration committed to individually counselling perpetrators and zero-tolerance for racism.

The Working Group notes with deep concern, the lack of representation of people of African descent in the judiciary, law enforcement, government service, correctional service, municipal councils, regional and federal parliaments. These institutions do not reflect the diversity of the Belgian population. When the Working Group visited Belgium in 2005, the federal police reported the existence of a robust recruitment program to promote diversity. While this program was again presented as a serious commitment, no data are currently available to establish what improvements, if any, had been made in the past fourteen years and whether the program has been successful.

Civil society and community members commented on the lack of positive role models in the news media, on billboards, and in Belgian television and film. The French Community referenced best practices involving a barometer of print media aimed at measuring equality and diversity among journalists and in news content, and creating of an expert panel to broaden representation.

The Working Group noted deficiencies in the enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights, among people of African descent in Belgium. According to research, sixty percent of Afro-Belgians are educated to degree level, but they are four times more likely to be unemployed than the national average. Eighty percent say they have been victims of discrimination from a very young age. Public officials consistently rationalized systematic exclusion of people of African descent with references to language and culture, even in cases involving second generation Belgians.

The Working Group repeatedly heard from civil society that Belgians of African descent faced “downgrading” and other employment challenges. People with university and graduate degrees reported working well-below their educational levels, including in manual labor despite possessing university certificates from Belgian universities. They also highlighted the difficulty in obtaining recognition of foreign diplomas. They also reported systematic exclusion from job assistance as job centers declined to refer people of African descent to employment opportunities at their educational levels. UNIA has also documented pervasive downgrading of employment and the prevalence of people of African descent working well below their education levels, despite the fact that they are among the most educated in the Belgian society.

The Working Group is concerned that primary and secondary school curricula do not adequately reflect the history of colonization as well as history and contributions of people of African descent in Belgium. Whether colonial history of Belgium is mentioned is largely dependent on interest and initiative of individual teachers. Where curriculum exists, it appears to recapitulate colonial propaganda including the suggestion that economic development came to Africa as a result of colonization while omitting references to key historical figures of African descent such as Patrice Lumumba. Reportedly, one-fourth of the high school graduates are unaware that Congo was a former Belgian colony.

At every interaction with civil society, the Working Group heard testimonies of the systematic practice of diverting children of African descent to vocational or manual training and out of the general education trajectory. This severely impacts the right to education and the right to childhood. Parents reported struggling to keep their children from being diverted, resisting transfers to vocational education, fighting to avoid having their children classified with behavioural or learning disorders and being threatened with the involvement of child protective services. A few parents discussed creative strategies to navigate these systems and secure their children’s education, including using the home school testing process and enrolling their children in boarding school. University students also reported being discouraged from continuing their educations or progressing.

Several community members discussed severe impact to their mental health due to racial discrimination. This included individualized racial slurs and hostile treatment, and several members of civil society in different locations mentioned the dramatic impact of daily racism on their lives – including depression and becoming withdrawn – and the fact that no one in authority in their schools ever noticed or intervened.

Civil society reported frequent discrimination in housing and rental markets. They would be immediately rejected by landlords who could detect an African accent over the phone or who recognized their names as African or informed the apartment was unavailable once they met the landlord face-to-face. Government informed of the use of “mystery calls,” a process involving the use of testers where landlords were identified as potentially discriminating unlawfully. The program was only recently commenced, pursuant to the Unia report and in conjunction with them, and few cases had been completed at the time of our visit.

The Working Group heard considerable testimony from civil society and community members on intersectionality, that people who meet the criteria for multiple marginalized groups may be particularly vulnerable, face extreme violence and harassment, and yet often remain invisible or deprioritized even within communities of African descent. This is particularly true for undocumented people of African descent whose lives are particularly precarious and who lack regularisation for years. In addition, women of African descent, particularly recent migrants, faced challenges pursuing justice, social support, or even shelter for domestic violence.

People of African descent and Muslim religious identity questioned why law enforcement authorities assumed they had terrorist ties. Some public officials implicitly acknowledged their role in this, including defending the use of racial profiling as a counter terrorism tactic and suggesting a false equivalence between anti-radicalism efforts and anti-racism programs, i.e., failing to understand that race-based assumptions regarding radicalism are inaccurate, grounded in bias, and divert key resources from protecting Belgian society from actual threats.

The Working Group is concerned about the rise of populist nationalism, racist hate speech and xenophobic discourse as a political tool. We reiterate the concerns raised by the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination in 2015 that the government has yet to adopt legislation declaring organizations which promote and incite racial discrimination illegal, in conformity with Article 4 of the Convention.

The use of blackface, racialized caricatures, and racist representations of people of African descent is offensive, dehumanizing and contemptuous. Regrettably, the re-publication of Tintin in the Congo unedited and without contextualization perpetuates negative stereotypes and either should be withdrawn or contextualized with an addendum reflecting current commitments to anti-racism.

The Working Group found little awareness about the International Decade for people of African descent. Civil society stands ready to support implementation of the Programme of Activities of the International Decade.

The following recommendations are intended to assist Belgium in its efforts to combat all forms of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, Afrophobia and related intolerance:

The Government of Belgium should adopt a comprehensive inter-federal National Action Plan against racism, upholding the commitments it made 2002, following the World Conference Against Racism. The National Action Plan against racism should be developed in partnership with people of African descent.

Adopt a National Strategy for the inclusion of people of African descent in Belgium, including migrants, and create a National Platform for people of African descent.

Establish an independent National Human Rights Institution, in conformity with the Paris Principles, and in partnership with people of African descent.

The Government should consider ratifying the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families.

The Working Group urges the Government to comply with the recommendations made by the Unia, including those relating to combating racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance.

The Working Group urges the government to fund creative projects by people of African descent such as the House of African Culture, among others, with the view of raising the visibility of all forms of African expression and preserving the history and memory of the African Diaspora.

We urge universities throughout Belgium to endow chairs in African Studies, and prioritize the hiring of faculty of African descent, with the view to foster research and the dissemination of knowledge in this area, as well as to diversify the academy.

The Government should ensure funding for anti-racism associations run by people of African descent to enable them to be partners in combatting racism. The Working Group also recommends inclusive financing mechanisms for entrepreneurs of African Descent.

We welcome the renaming of the former Square du Bastion to Patrice Lumumba Square in June 2018 as well as an exhibit commemorating Congolese soldiers who fought in World War I, and encourage further, durable commemoration of contributions of people of African descent and the removal of markers of the colonial period.

We urge the government to give recognition and visibility to those who were killed during the period of colonization, to Congolese soldiers who fought during the two World Wars, and to acknowledge the cultural, economic, political and scientific contributions of people of African descent to the development of Belgian society through the establishment of monuments, memorial sites, street names, schools, municipal, regional and federal buildings. This should be done in consultation with civil society.

The Working Group recommends reparatory justice, with a view to closing the dark chapter in history and as a means of reconciliation and healing. We urge the government to issue an apology for the atrocities committed during colonization. The right to reparations for past atrocities is not subject to any statute of limitations. The Working Group recommends the CARICOM 10-point action plan for reparatory justice as a guiding framework.

The Working Group supports the establishment of a truth commission, and supports the draft bill before Parliament entitled “A memorial work plan to establish facts and the implication of Belgian institutions in Congo, Rwanda and Burundi”, dated 14 February 2017.

The authorities should ensure full access to archives relevant for research on Belgian colonialism.

The Working Group urges the relevant authorities to ensure that the RMCA be entrusted with tasks and responsibilities in the context of the International Decade for people of African Descent. In this context, the Working Group recommends that the RMCA be provided with appropriate financial and human resources, which would allow it to fully exercise the potential of this institution and engage in further improving and enriching its narrative, thus contributing to a better awareness and understanding of the tragic legacies of Belgian colonialism as well as past and contemporary human rights challenges of people of African descent.

The Working Group encourages the RMCA, in collaboration with historians from Africa and the diaspora, to remove all offensive racist exhibits and ensure detailed explanations and context to inform and educate visitors accurately about Belgium’s colonial history and its exploitation of Africa.

The Working Group urges the Government to provide specific, directed funding to the RMCA to enrich its postcolonial analysis. This funding should allow for innovations like QR codes on museum placards to provide more context and enrich intersectional analyses, including the historical and current interplay of race, gender, sexuality, migration status, religion and other relevant criteria.

The Working Group urges the Government to financially support a public education campaign in partnership with people of African descent, to learn and better understand the legacies of Belgian colonialism.

The Working Group strongly recommends that the Government collects, compiles, analyses, disseminates and publishes reliable statistical data disaggregated by race and on the basis of voluntary self-identification, and undertakes all necessary measures to assess regularly the situation of individuals and groups of individuals who are victims of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance.

The Working Group calls on the Government to address racial profiling and institute a policy of documenting and analyzing stops and searches nationwide, including race and skin color, in order to promote and ensure equality and fairness on policing; mitigate selective enforcement of the law; address enduring bias, stereotype, and beliefs about the need to surveil and control people of African descent.

Ensure that the robust framework set up for the prosecution of hate crimes is used more in practice.

Review diversity initiatives within justice institutions as well as other sectors including education and media, to develop clear benchmarks to increase diversity measurably and overcome structural discrimination and unconscious bias through positive measures, in accordance with the provisions of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination.

Clarify and simplify jurisdiction of anti-discrimination authorities, creating one point of entry to ease reporting for victims and to coordinate and enhance accountability for perpetrators of racist harassment and violence, including accelerated judicial procedures.

The Government should review and ensure that textbooks and educational materials accurately reflect historical facts as they relate to past tragedies and atrocities such as enslavement, the trade in enslaved Africans and colonialism. Belgium should use UNESCO’s General History of Africa to inform its educational curriculum, among similarly oriented authoritative texts. We urge the government to promote greater knowledge and recognition of and respect for the culture, history and heritage of people of African descent living in Belgium. This should include the mandatory teaching of Belgium’s colonial history at all levels of the education system.

The Ministries of Education and the local Communities must determine whether there is a statistically significant difference in diversion of children of African descent from mainstream education into vocational or technical education streams, as compared to white Belgian children.

All teachers should complete anti-racism training, including training on implicit bias and specific manifestations in the context of their work. The training should involve testing to evaluate the understanding of diversity among teachers.

All public officials charged with education responsibilities must develop clear, objective, and transparent processes and criteria that govern when a child should be diverted from mainstream education, the need to guard against implicit bias and race-based outcomes in decision-making, and the right of parents to resist or overrule the recommendations of teachers without harassment.

The Government should take all necessary measures to combat racial discrimination and ensure full implementation of the right to adequate standard of living, including the right to adequate housing, access to affordable health care, employment and education for people of African descent.

Invest in integrated trust-building measures between the police, judicial institutions, the Unia, social integration institutions, anti-racist associations, and victims of racial discrimination and race and gender based violence, to ensure that racist acts, violence or crimes are systematically reported, prosecuted and compensated.

Belgium should conduct a racial equity audit within its public institutions and incentivize private employers and institutions to do the same. The purpose of the audit is to look for systemic bias and discrimination within the regular and routine operation of business. Belgium should commit to a public release of the findings and to implementing recommendations developed in the audit process.

Belgium should examine existing statistics and proxy data to determine whether people of African descent in Belgium, including Belgian citizens of African descent, experience and exercise their human rights consistently with the averages for all Belgians. This includes data on citizenship, parents’ place of birth, and regroupement famille (family reunification) data for reunification from countries of African descent.

Belgium should adopt clear, objective, and transparent protocols for job centers to ensure they do not perpetuate stereotype and bias, including requiring referrals to be based on level of education or experience, and recognizing that language should not be a disqualifying factor once a measurable competence is determined.

The Working Group recommends the Government support and facilitate an open debate on the use of blackface, racialized caricatures and racist representation of people of African descent. The republication of Tintin in the Congo should be withdrawn or contextualized with an addendum reflecting current commitments to anti-racism.

The Working Group calls on politicians at all levels of society to avoid instrumentalzing racism, xenophobia and hate speech in the pursuit of political office and to encourages them to promote inclusion, solidarity, non-discrimination and meaningful commitments to equality. Media is also reminded of its important role in this regard.

The Working Group reminds media of their important role as a public watchdog with special responsibilities for ensuring that factual and reliable information about people of African descent is reported.

The Working Group urges the Government to involve civil society organisations representing people of African descent when framing important legislations concerning them and providing those organizations with adequate funding.

The International Decade on People of African Descent should be officially launched in Belgium at the federal level.

The Working Group also encourages the Government to further implement the 2030 Sustainable Development Agenda within Belgium, with focus on indicators relevant for people of African descent, in partnership with civil society. In view of Statbel’s 2018 report on poverty, the Working Group calls on the government to eradicate structural racism to attain the Sustainable Development Goals.

The Working Group would like to reiterate its satisfaction at the Government’s willingness to engage in dialogue, cooperation and action to combat racial discrimination. We hope that our report will support the Government in this process and we express our willingness to assist in this important endeavour.

****

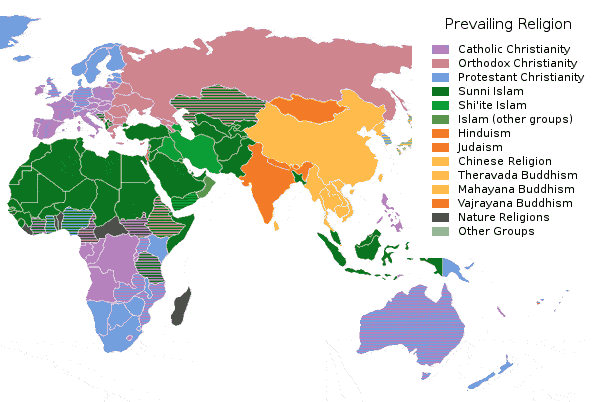

Kaart der overheersende religies

ID: 201604122149

According to a recent study (based on the 2010 world population of 6.9 billion) by The Pew Forum, there are:

2,173,180,000 Christians (31% of world population), of which 50% are Catholic, 37% Protestant, 12% Orthodox, and 1% other.

1,598,510,000 Muslims (23%), of which 87-90% are Sunnis, 10-13% Shia.

1,126,500,000 No Religion affiliation (16%): atheists, agnostics and people who do not identify with any particular religion. One-in-five people (20%) in the United States are religiously unaffiliated.

1,033,080,000 Hindus (15%), the overwhelming majority (94%) of which live in India.

487,540,000 Buddhists (7%), of which half live in China.

405,120,000 Folk Religionists (6%): faiths that are closely associated with a particular group of people, ethnicity or tribe.

58,110,000 Other Religions (1%): Baha’i faith, Taoism, Jainism, Shintoism, Sikhism, Tenrikyo, Wicca, Zoroastrianism and many others.

13,850,000 Jews (0.2%), four-fifths of which live in two countries: United States (41%) and Israel (41%).

bron: http://www.worldometers.info/world-population/#table-historical

Islamization and Demographic Denialism in France

ID: 201603141661

by Michel Gurfinkiel

PJ Media

March 14, 2016

Excerpt of an article originally published under the title "Latest Survey Finds 25% of French Teenagers Are Muslims."

One of the most striking cases of reality denial in contemporary France is demography: issues like birthrate, life expectancy, immigration, and emigration. On the face of it, you can hardly ignore such things, since they constantly reshape your environment and your way of life. Even without resorting to statistics, you are bound to perceive, out of day-to-day experience, what the current balance is between younger and older people, how many kids are to be found at an average home, and the ethnicity or religion of your neighbors, or the people you relate to at work or in business.

The French elites, both on the right and left, managed for five decades at least to dismiss the drastic demographic changes that had been taking place in their country, including the rise of Islam, since they clashed with too many political concepts – or fantasies – they had been brainwashed into accepting: the superiority of the "French social model;" the unique assimilative capacity of French society; equality for equality's sake; the primacy of individual values over family values; secularism; francophonie, or the assumption that all French-speaking nations in the world were a mere extension of France, and that all nations that defined themselves as "Francophone" did speak French or were subdued by French culture; and finally la politique arabe et islamique de la France, a supposed political and strategic affinity with the Arab and Muslim world.

Until 2004, compilation of ethnic, racial, and religious statistics was prohibited under French law.

One way for the elites to deny demographics was to reject ethnic-related investigation on legal or ethical grounds. Until 2004, ethnic, racial, and religious statistics were not allowed under French law – ostensibly to prevent a return of Vichy State-style racial persecutions. Even as the law was somehow relaxed, first in 2004 and again in 2007, many statisticians or demographers insisted on retaining a de facto ban on such investigations.

The issue turned into a nasty civil war among demographers, and especially within INED (the French National Institute for Demographic Studies) between a "classic" wing led by older demographers like Henri Léridon and Gérard Calot and then by the younger Michèle Tribalat, and a liberal or radical wing led by Hervé Le Bras.

Michèle Tribalat

In a recent interview with the French weekly Le Point, Tribalat dryly observed that the "well-connected" Le Bras described her as "the National Front Darling," an assertion that "destroyed her professional reputation." The son of a prestigious Catholic historian, Le Bras is indeed a very powerful man in his own right, who managed throughout his own career to accumulate tenures, honors, and positions of influence both in France and abroad.

The irony about his accusation against Tribalat is that, while intent to discuss the issue of immigration, she is an extremely cautious and conservative expert when it comes to actual figures. She has always tended to play down, in particular, the size of the French Muslim community.

In 1997, I observed in an essay for Middle East Quarterly that figures about French Islam were simply chaotic: there was too much discrepancy between sources:

The Ministry of Interior and Ined routinely speak of a Muslim population in France of 3 million. Sheikh Abbas, head of the Great Mosque in Paris, in 1987 spoke of twice as many – 6 million. Journalists usually adopt an estimate somewhere in the middle: for example, Philippe Bernard of Le Monde uses the figure of 3 to 4 million. The Catholic Church, a reliable source of information on religious trends in France, also estimates 4 million. Arabies, a French-Arab journal published in Paris, provides the following breakdown: 3.1 million Muslims of North African origin, 400,000 from the Middle East, 300,000 from Africa, 50,000 Asians, 50,000 converts of ethnic French origin, and 300,000 illegal immigrants from unknown countries. This brings the total to 4.2 million. One can state with reasonable certainty that the Muslim population of France numbers over 3 million (about 5 percent of the total French population) and quite probably over 4 million (6.6 percent).

Nineteen years later, accuracy has hardly improved in this respect. All sources agree that France as a whole underwent a moderate demographic growth: from 57 to 67 million, a 15% increase. (Throughout the same period of time, the U.S. enjoyed a 22% population increase, and China, under a government-enforced one-child policy, a 27% increase.) All sources agree also that there was a much sharper increase in French Muslim demographics – and that, accordingly, the moderate national growth may in fact just reflect the Muslim growth.

For all that, however, there are still no coherent figures about the Muslim community. According to CSA, a pollster that specializes in religious surveys, 6% of the citizens and residents of France identified with Islam in 2012: about 4 million people out of 65 million. IFOP, a leading national pollster, settled for 7% in 2011: 4.5 million. Pew concluded in 2010 a figure of 7.5%: 4.8 million. The CIA World Factbook mentioned 7% to 9% in 2015: from 4.6 to almost 6 million out of 66 million. INED claimed as early as 2009 an 8% figure: 5.1 million. Later, INED and French government sources gave 9% in 2014: 5.8 million.

Over two decades, the French Muslim population is thus supposed to have increased by 25% according to the lowest estimations, by 50% according to median estimations, or even by 100% if one compares the INED and government figures of 1997 to those of 2014, from 3 million to almost 6 million.

This is respectively almost two times, three times, or six times the French average population growth.

An impressive leap forward, whatever the estimation. But even more impressive is, just as was the case in 1997, the discrepancy between the estimates. Clearly, one set of estimates, at least, must be entirely erroneous. And it stands to reason that the lowest estimates are the least reliable.

First, we have a long-term pattern according to which, even within the lowest estimates, the Muslim population increase is accelerating. One explanation is that the previous low estimates were inaccurate.

Second, low estimates tend to focus on the global French population on one hand and on the global French Muslim population on the other hand, and to bypass a generational factor. The younger the population cohorts, the higher the proportion of Muslims. This is reflected in colloquial French by the widespread metonymical substitution of the word "jeune" (youth) for "jeune issu de l'immigration" (immigrant youth), or "jeune issu de la diversité" (non-European or non-Caucasian youth).

According to the first ethnic-related surveys released in early 2010, fully a fifth of French citizens or residents under twenty-four were Muslims.

Proportions were even higher in some places: 50% of the youth were estimated to be Muslim in the département (county) of Seine-Saint-Denis in the northern suburbs of Paris, or in the Lille conurbation in Northern France. A more recent survey validates these numbers.

Once proven wrong, deniers do not make amends. They move straight from fantasy to surrender.

An investigation of the French youths' religious beliefs was conducted last spring by Ipsos. It surveyed nine thousand high school pupils in their teens on behalf of the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and Sciences Po Grenoble.

The data was released on February 4, 2016, by L'Obs, France's leading liberal newsmagazine. Here are its findings:

38.8% of French youths do not identify with a religion.

33.2% describe themselves as Christian.

25.5% call themselves Muslim.

1.6% identify as Jewish.

Only 40% of the young non-Muslim believers (and 22% of the Catholics) describe religion as "something important or very important."

But 83% of young Muslims agree with that statement.

Such figures should deal the death blow to demographic deniers. Except that once proven wrong, deniers do not make amends. Rather, they contend that since there is after all a demographic, ethnic, and religious revolution, it should be welcomed as a good and positive thing. Straight from fantasy to surrender.

Michel Gurfinkiel, a Shillman-Ginsburg Fellow at the Middle East Forum, is the founder and president of the Jean-Jacques Rousseau Institute, a conservative think tank in France.

PJ Media

March 14, 2016

Excerpt of an article originally published under the title "Latest Survey Finds 25% of French Teenagers Are Muslims."

One of the most striking cases of reality denial in contemporary France is demography: issues like birthrate, life expectancy, immigration, and emigration. On the face of it, you can hardly ignore such things, since they constantly reshape your environment and your way of life. Even without resorting to statistics, you are bound to perceive, out of day-to-day experience, what the current balance is between younger and older people, how many kids are to be found at an average home, and the ethnicity or religion of your neighbors, or the people you relate to at work or in business.

The French elites, both on the right and left, managed for five decades at least to dismiss the drastic demographic changes that had been taking place in their country, including the rise of Islam, since they clashed with too many political concepts – or fantasies – they had been brainwashed into accepting: the superiority of the "French social model;" the unique assimilative capacity of French society; equality for equality's sake; the primacy of individual values over family values; secularism; francophonie, or the assumption that all French-speaking nations in the world were a mere extension of France, and that all nations that defined themselves as "Francophone" did speak French or were subdued by French culture; and finally la politique arabe et islamique de la France, a supposed political and strategic affinity with the Arab and Muslim world.

Until 2004, compilation of ethnic, racial, and religious statistics was prohibited under French law.

One way for the elites to deny demographics was to reject ethnic-related investigation on legal or ethical grounds. Until 2004, ethnic, racial, and religious statistics were not allowed under French law – ostensibly to prevent a return of Vichy State-style racial persecutions. Even as the law was somehow relaxed, first in 2004 and again in 2007, many statisticians or demographers insisted on retaining a de facto ban on such investigations.

The issue turned into a nasty civil war among demographers, and especially within INED (the French National Institute for Demographic Studies) between a "classic" wing led by older demographers like Henri Léridon and Gérard Calot and then by the younger Michèle Tribalat, and a liberal or radical wing led by Hervé Le Bras.

Michèle Tribalat

In a recent interview with the French weekly Le Point, Tribalat dryly observed that the "well-connected" Le Bras described her as "the National Front Darling," an assertion that "destroyed her professional reputation." The son of a prestigious Catholic historian, Le Bras is indeed a very powerful man in his own right, who managed throughout his own career to accumulate tenures, honors, and positions of influence both in France and abroad.

The irony about his accusation against Tribalat is that, while intent to discuss the issue of immigration, she is an extremely cautious and conservative expert when it comes to actual figures. She has always tended to play down, in particular, the size of the French Muslim community.

In 1997, I observed in an essay for Middle East Quarterly that figures about French Islam were simply chaotic: there was too much discrepancy between sources:

The Ministry of Interior and Ined routinely speak of a Muslim population in France of 3 million. Sheikh Abbas, head of the Great Mosque in Paris, in 1987 spoke of twice as many – 6 million. Journalists usually adopt an estimate somewhere in the middle: for example, Philippe Bernard of Le Monde uses the figure of 3 to 4 million. The Catholic Church, a reliable source of information on religious trends in France, also estimates 4 million. Arabies, a French-Arab journal published in Paris, provides the following breakdown: 3.1 million Muslims of North African origin, 400,000 from the Middle East, 300,000 from Africa, 50,000 Asians, 50,000 converts of ethnic French origin, and 300,000 illegal immigrants from unknown countries. This brings the total to 4.2 million. One can state with reasonable certainty that the Muslim population of France numbers over 3 million (about 5 percent of the total French population) and quite probably over 4 million (6.6 percent).

Nineteen years later, accuracy has hardly improved in this respect. All sources agree that France as a whole underwent a moderate demographic growth: from 57 to 67 million, a 15% increase. (Throughout the same period of time, the U.S. enjoyed a 22% population increase, and China, under a government-enforced one-child policy, a 27% increase.) All sources agree also that there was a much sharper increase in French Muslim demographics – and that, accordingly, the moderate national growth may in fact just reflect the Muslim growth.

For all that, however, there are still no coherent figures about the Muslim community. According to CSA, a pollster that specializes in religious surveys, 6% of the citizens and residents of France identified with Islam in 2012: about 4 million people out of 65 million. IFOP, a leading national pollster, settled for 7% in 2011: 4.5 million. Pew concluded in 2010 a figure of 7.5%: 4.8 million. The CIA World Factbook mentioned 7% to 9% in 2015: from 4.6 to almost 6 million out of 66 million. INED claimed as early as 2009 an 8% figure: 5.1 million. Later, INED and French government sources gave 9% in 2014: 5.8 million.

Over two decades, the French Muslim population is thus supposed to have increased by 25% according to the lowest estimations, by 50% according to median estimations, or even by 100% if one compares the INED and government figures of 1997 to those of 2014, from 3 million to almost 6 million.

This is respectively almost two times, three times, or six times the French average population growth.

An impressive leap forward, whatever the estimation. But even more impressive is, just as was the case in 1997, the discrepancy between the estimates. Clearly, one set of estimates, at least, must be entirely erroneous. And it stands to reason that the lowest estimates are the least reliable.

First, we have a long-term pattern according to which, even within the lowest estimates, the Muslim population increase is accelerating. One explanation is that the previous low estimates were inaccurate.

Second, low estimates tend to focus on the global French population on one hand and on the global French Muslim population on the other hand, and to bypass a generational factor. The younger the population cohorts, the higher the proportion of Muslims. This is reflected in colloquial French by the widespread metonymical substitution of the word "jeune" (youth) for "jeune issu de l'immigration" (immigrant youth), or "jeune issu de la diversité" (non-European or non-Caucasian youth).

According to the first ethnic-related surveys released in early 2010, fully a fifth of French citizens or residents under twenty-four were Muslims.

Proportions were even higher in some places: 50% of the youth were estimated to be Muslim in the département (county) of Seine-Saint-Denis in the northern suburbs of Paris, or in the Lille conurbation in Northern France. A more recent survey validates these numbers.

Once proven wrong, deniers do not make amends. They move straight from fantasy to surrender.

An investigation of the French youths' religious beliefs was conducted last spring by Ipsos. It surveyed nine thousand high school pupils in their teens on behalf of the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and Sciences Po Grenoble.

The data was released on February 4, 2016, by L'Obs, France's leading liberal newsmagazine. Here are its findings:

38.8% of French youths do not identify with a religion.

33.2% describe themselves as Christian.

25.5% call themselves Muslim.

1.6% identify as Jewish.

Only 40% of the young non-Muslim believers (and 22% of the Catholics) describe religion as "something important or very important."

But 83% of young Muslims agree with that statement.

Such figures should deal the death blow to demographic deniers. Except that once proven wrong, deniers do not make amends. Rather, they contend that since there is after all a demographic, ethnic, and religious revolution, it should be welcomed as a good and positive thing. Straight from fantasy to surrender.

Michel Gurfinkiel, a Shillman-Ginsburg Fellow at the Middle East Forum, is the founder and president of the Jean-Jacques Rousseau Institute, a conservative think tank in France.

Politieke affiliatie en religie in de USA

ID: 201603031426

Surveys have often shows that religion is an important aspect of an American presidential race. The electorate frequently say that it's important to have a a president with strong religious beliefs in office. Pew Research recently pubslished some interesting data showing the political leanings of several major religious groups in the US. Mormons tend to be strongly Republican while Jews, Muslims and Buddhists identify more with the Democrats. Catholics are strongly divided with 37 percent leaning towards the Republicans and 44 percent towards the Democrats.

Surveys have often shows that religion is an important aspect of an American presidential race. The electorate frequently say that it's important to have a a president with strong religious beliefs in office. Pew Research recently pubslished some interesting data showing the political leanings of several major religious groups in the US. Mormons tend to be strongly Republican while Jews, Muslims and Buddhists identify more with the Democrats. Catholics are strongly divided with 37 percent leaning towards the Republicans and 44 percent towards the Democrats.This chart shows the political affiliation of selected US religious groups in 2014.

Land: USA

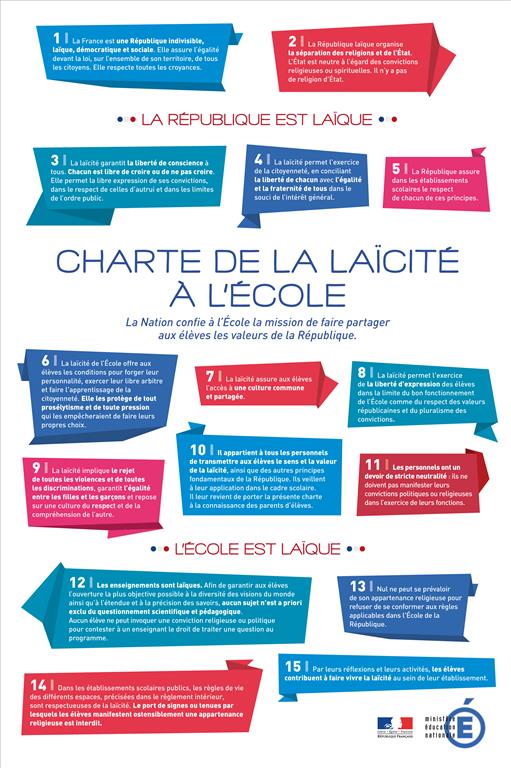

Charte de la laïcité à l’école.

ID: 201510090957

La Nation confie à l’école la mission de faire partager aux élèves les valeurs de la République. La République est laïque. L’école est laïque.

1) La France est une République indivisible, laïque, démocratique et sociale. Elle assure l’égalité devant la loi, sur l’ensemble de son territoire, de tous les citoyens. Elle respecte toutes les croyances.

2) La République laïque organise la séparation des religions et de l’État. L’État est neutre à l’égard des convictions religieuses ou spirituelles. Il n’y a pas de religion d’État.

3) La laïcité garantit la liberté de conscience à tous. Chacun est libre de croire ou de ne pas croire. Elle permet la libre expression de ses convictions, dans le respect de celles d’autrui et dans les limites de l’ordre public.

4) La laïcité permet l’exercice de la citoyenneté, en conciliant la liberté de chacun avec l’égalité et la fraternité de tous dans le souci de l’intérêt général.

5) La République assure dans les établissements scolaires le respect de chacun de ces principes.

6) La laïcité de l’École offre aux élèves les conditions pour forger leur personnalité, exercer leur libre arbitre et faire l’apprentissage de la citoyenneté. Elle les protège de tout prosélytisme et de toute pression qui les empêcheraient de faire leurs propres choix.

7) La laïcité assure aux élèves l’accès à une culture commune et partagée.

8) La laïcité permet l’exercice de la liberté d’expression des élèves dans la limite du bon fonctionnement de l’École comme du respect des valeurs républicaines et du pluralisme des convictions.

9) La laïcité implique le rejet de toutes les violences et de toutes les discriminations, garantit l’égalité entre les filles et les garçons et repose sur une culture du respect et de la compréhension de l’autre.

10) Il appartient à tous les personnels de transmettre aux élèves le sens et la valeur de la laïcité, ainsi que des autres principes fondamentaux de la République. Ils veillent à leur application dans le cadre scolaire. Il leur revient de porter la présente charte à la connaissance des parents d’élèves.

11) Les personnels ont le devoir de stricte neutralité : ils ne doivent pas manifester leurs convictions politiques ou religieuses dans l’exercice de leurs fonctions.

12) Les enseignements sont laïques. Afin de garantir aux élèves l’ouverture la plus objective possible à la diversité des visions du monde ainsi qu’à l’étendue et à la précision des savoirs, aucun sujet n’est a priori exclu du questionnement scientifique et pédagogique. Aucun élève ne peut invoquer une conviction religieuse ou politique pour contester à un enseignant le droit de traiter une question au programme.

13) Nul ne peut se prévaloir de son appartenance religieuse pour refuser de se conformer aux règles applicables dans l’École de la République.

14) Dans les établissements scolaires publics, les règles de vie des différents espaces, précisées dans le règlement intérieur, sont respectueuses de la laïcité. Le port de signes ou tenues par lesquels les élèves manifestent ostensiblement une appartenance religieuse est interdit.

15) Par leurs réflexions et leurs activités, les élèves contribuent à faire vivre la laïcité au sein de leur établissement.

1) La France est une République indivisible, laïque, démocratique et sociale. Elle assure l’égalité devant la loi, sur l’ensemble de son territoire, de tous les citoyens. Elle respecte toutes les croyances.

2) La République laïque organise la séparation des religions et de l’État. L’État est neutre à l’égard des convictions religieuses ou spirituelles. Il n’y a pas de religion d’État.

3) La laïcité garantit la liberté de conscience à tous. Chacun est libre de croire ou de ne pas croire. Elle permet la libre expression de ses convictions, dans le respect de celles d’autrui et dans les limites de l’ordre public.

4) La laïcité permet l’exercice de la citoyenneté, en conciliant la liberté de chacun avec l’égalité et la fraternité de tous dans le souci de l’intérêt général.

5) La République assure dans les établissements scolaires le respect de chacun de ces principes.

6) La laïcité de l’École offre aux élèves les conditions pour forger leur personnalité, exercer leur libre arbitre et faire l’apprentissage de la citoyenneté. Elle les protège de tout prosélytisme et de toute pression qui les empêcheraient de faire leurs propres choix.

7) La laïcité assure aux élèves l’accès à une culture commune et partagée.

8) La laïcité permet l’exercice de la liberté d’expression des élèves dans la limite du bon fonctionnement de l’École comme du respect des valeurs républicaines et du pluralisme des convictions.

9) La laïcité implique le rejet de toutes les violences et de toutes les discriminations, garantit l’égalité entre les filles et les garçons et repose sur une culture du respect et de la compréhension de l’autre.

10) Il appartient à tous les personnels de transmettre aux élèves le sens et la valeur de la laïcité, ainsi que des autres principes fondamentaux de la République. Ils veillent à leur application dans le cadre scolaire. Il leur revient de porter la présente charte à la connaissance des parents d’élèves.

11) Les personnels ont le devoir de stricte neutralité : ils ne doivent pas manifester leurs convictions politiques ou religieuses dans l’exercice de leurs fonctions.

12) Les enseignements sont laïques. Afin de garantir aux élèves l’ouverture la plus objective possible à la diversité des visions du monde ainsi qu’à l’étendue et à la précision des savoirs, aucun sujet n’est a priori exclu du questionnement scientifique et pédagogique. Aucun élève ne peut invoquer une conviction religieuse ou politique pour contester à un enseignant le droit de traiter une question au programme.

13) Nul ne peut se prévaloir de son appartenance religieuse pour refuser de se conformer aux règles applicables dans l’École de la République.

14) Dans les établissements scolaires publics, les règles de vie des différents espaces, précisées dans le règlement intérieur, sont respectueuses de la laïcité. Le port de signes ou tenues par lesquels les élèves manifestent ostensiblement une appartenance religieuse est interdit.

15) Par leurs réflexions et leurs activités, les élèves contribuent à faire vivre la laïcité au sein de leur établissement.

ID: 201510060209

It's easy if you try

No hell below us

Above us only sky

Imagine all the people

Living for today

Imagine there's no countries,

It isn't hard to do

Nothing to kill or die for

And no religion too

Imagine all the people

Living life in peace

You may say I'm a dreamer

But I'm not the only one

I hope some day you'll join us

And the world will be as one

Imagine no possessions

I wonder if you can

No need for greed or hunger

A brotherhood of man

Imagine all the people

Sharing all the world

You may say I'm a dreamer

But I'm not the only one

I hope some day you'll join us

And the world will live as one

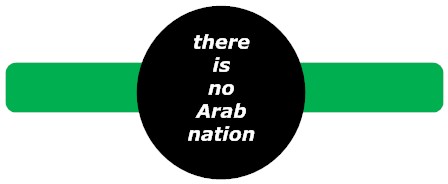

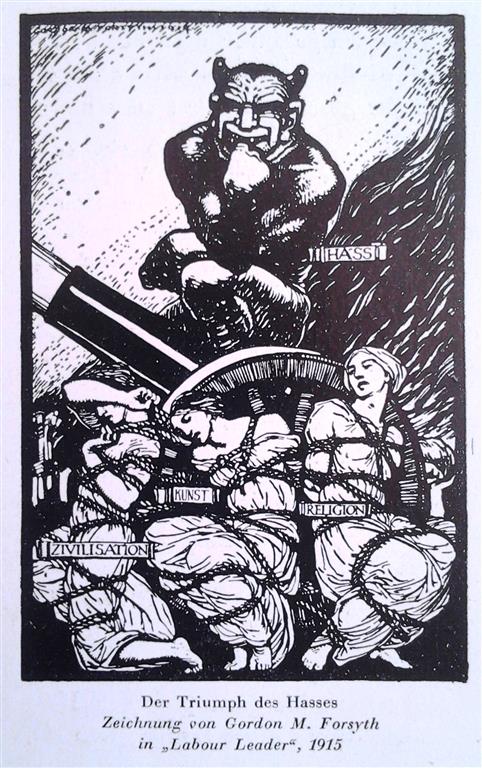

The Wrath of Nations - 1993

ID: 201509161527

'There is no Arab nation, as such. The historical experience and reference of the region is not to nation but to religion, commune, empire, caliphate. The states which exist there today do so because it is now considered appropriate that people live in nation-states, not in multiconfessional and multinational empires.' (111)

'The identification of religion with civilization in Islamic society blocks a solution to its contemporary problems.' (123)

link to website William Pfaff does not function anymore

William Pfaff (December 29, 1928 – April 30, 2015) was an American author, op-ed columnist for the International Herald Tribune and frequent contributor to The New York Review of Books. (wiki)

'The identification of religion with civilization in Islamic society blocks a solution to its contemporary problems.' (123)

link to website William Pfaff does not function anymore

William Pfaff (December 29, 1928 – April 30, 2015) was an American author, op-ed columnist for the International Herald Tribune and frequent contributor to The New York Review of Books. (wiki)

Le Pillage des biens nationaux. Une Famille française sous la Révolution

ID: 201504070912

L'extrait qui fait suite, est tiré de l'ouvrage de Paul de Pradel de Lamase (1849-1936), "Le Pillage des biens nationaux. Une Famille française sous la Révolution". Il illustre une bien courte partie de la vie du château d'allassac (mais pas que lui) sur lequel je faisais quelques recherches.

Malgré le caractère "conséquent" de la citation, j'ai tenu pourtant à garder ce chapitre intact et complet car sa richesse et son contenu donne un éclairage très particulier, que je n'ai pas souvent rencontré, de la révolution Française dans son ensemble et une vue précise de l'agonie du château d'allassac.

Il me semble évident qu'une certaine forme de partialité concernant la période révolutionnaire se dégage de ce texte, même si les faits exposés semblent avoir été vérifiés et prouvés, il n'en reste pas moins que les actions décrites mettent surtout l'accent sur le vandalisme de la révolution, et laissent plus largement sous silence les motivations souvent justifiées de certains de sortir d'un régime que nous n'avons toutefois jamais vraiment quitté. N'ayant pas souvent sous les yeux la vision qua pu avoir l'auteur il m'a semblé interessant de la partager.

A plusieurs reprises lors de la lecture, l'auteur se livre à des analyses qui semblent pertinentes et il sait mettre en avant les arguments que nous utiliserions encore aujourd'hui. De même, une fois passé le vocabulaire tranchant qu'il utilise pour qualifier certains groupes on découvre une personnes avisée et clairvoyante sur la nature humaine.

Pour le reste, la description des biens et de l'histoire de leur disparition est une pure merveille de rédaction et de précision qu'il m'est difficile de couper. Jugez en par vous même :

La curée

Le plus important est fait; la famille de Lamase est en exil; ses grands biens sont privés de l'oeil du maître ; il s'agit maintenant de les priver du maître lui même, de les nationaliser, en un mot. Pour cet objet, il n'y a plus qu'à laisser le plan révolutionnaire se développer dans toute sa beauté. Ce plan est simple : les propriétaires dont la fortune est adjugée d'avance aux affiliés sont d'abord contraints de sortir de France ; on les empêchera ensuite d'y rentrer; on les punira de la confiscation pour être sortis ou pour n'être pas rentrés, et le tour sera joué.

L'Assemblée Constituante accomplit en deux ans la première partie du programme. Elle provoque le désordre, elle encourage l'émeute, l'assassinat et le pillage; elle renverse les lois et coutumes établies depuis des siècles; elle anéantit les parlements et les anciennes juridictions indépendantes; elle les remplace par des tribunaux dont les juges sont à la nomination du pouvoir politique, par conséquent à sa dévotion. Toutes les institutions garantissant la vie et les propriétés des sujets du roi sont supprimées en théorie quand cette assemblée de malheur passe la main à la Législative, au mois d'octobre 1791. Les bons citoyens ne peuvent plus se faire aucune illusion. Le roi, avili et sans force, est incapable de les protéger; plus de cent mille familles vont chercher à l'étranger le minimum de protection auquel a droit tout homme civilisé.

Il ne faut qu'un an à la Législative pour exécuter la deuxième partie du programme, pour ouvrir l'ère des injustices les plus criantes, des scélératesses les plus effrontées.

Quand elle aura terminé son oeuvre, toutes les victimes désignées seront solidement ligotées; la Convention et le Directoire n'auront plus qu'à frapper dans le tas, les yeux fermés. Il ne sera même plus nécessaire de disposer de tribunaux dociles pour priver les citoyens de leur liberté, de leur fortune, au besoin de leur tête. Celle-ci sera parfois à la discrétion des geôliers qui s'amuseront à massacrer vingt-cinq ou trente mille prisonniers dans les premiers jours de septembre 1792; les survivants, on les laissera mourir de faim au fond des geôles puantes, ou on les guillotinera. Le résultat sera le même. Ni les uns ni les autres ne viendront réclamer leurs biens, et c'est le seul point essentiel.

J'ai dit que la Législative avait rétabli la loi de confiscation et aboli le droit naturel d'aller et de venir dont les Français avaient toujours joui.

L'acte d'émigration ayant passé « crime » digne de mort et de confiscation, l'heure avait sonné en Limousin de faire main basse sur le patrimoine du plus incontestablement riche et du plus bienfaisant seigneur de la contrée. Dès le mois de septembre 1792, mon bisaïeul fût inscrit sur la liste des émigrés. De quel droit ? Ses bourreaux ignoraient le lieu de sa retraite et ils ne firent aucune démarche pour la découvrir. M. de Lamase vivait à l'écart; dès que les jours devinrent très sombres, il avait pris un correspondant à Strasbourg, et toutes les lettres qu'il fit parvenir de sa retraite à ses compatriotes sont datées de cette ville alors française. Les prescripteurs devaient présumer qu'il n'avait pas franchi la frontière .

En l'inscrivant, sans plus ample informé, sur les tablettes de l'émigration, les administrateurs du district d'Uzerche, préjugeant le « crime » sans le constater, commettaient une première forfaiture. Je la signale ici pour mémoire, le chapitre suivant devant établir que le « coupable » ne fut jamais émigré, au sens que les lois homicides de l'époque attachaient à ce mot.

Les scellés furent apposés sur ses meubles et ses biens-fonds placés sous séquestre. C'était la première formalité de la dispersion aux quatre vents d'une fortune acquise par dix générations, au prix de mille efforts d'intelligence et d'économie.

Deux des frères de Jean de Lamase et un de ses fils, qui tous trois étaient restés dans leur province ou y étaient revenus, essayèrent d'obvier aux effets désastreux de cette mesure préparatoire en opposant à son exécution des moyens dilatoires, soit en revendiquant leur légitime sur les héritages, soit en se faisant nommer séquestres de quelques domaines, soit encore en rachetant aux enchères les meubles auxquels ils étaient particulièrement attachés.

Pauvres moyens ! Au jeu de l'intrigue les honnêtes gens en lutte avec les malfaiteurs ont toutes chances de succomber, car il est écrit depuis trois mille ans que « les enfants des ténèbres sont mieux avisés que les enfants de lumière dans la conduite des affaires temporelles ».

On le fit bien voir à ces infortunés. Les persécutions qu'ils endurèrent sur place furent parfois plus amères que celles de l'exil. Ils furent aussi bien et aussi complètement volés que le chef de famille... et bernés, par-dessus le marché ; ce qui est plus humiliant que d'être assassiné.

Quand on voulut mettre en vente les immeubles séquestrés, aucun acquéreur sérieux ne se présenta, tout d'abord.

C'était au commencement de 1793. Les fermiers seuls auraient eu l'audace de s'approprier les terres qu'ils avaient le cynisme de faire valoir, pour le compte de la nation; mais comme ils ne croyaient point à la durée de l'orgie; comme, d'autre part, ils ne payaient au département qu'un prix de fermage dérisoire, ils préféraient de beaucoup profiter de l'aubaine pour épuiser les champs et les vignes, en tirer le plus possible de revenus annuels et mettre ces revenus, convertis en numéraire, à l'abri des retours de la fortune.

Les paysans, les vrais, ceux qui mangent leur pain à la sueur de leur front, éprouvaient une horreur invincible à se souiller d'un vol perpétré à la face du soleil.

Leur conscience était restée et reste encore foncièrement respectueuse de la propriété d'autrui. Il existait, sur la question, un précédent qui leur fait trop d'honneur pour que je m'abstienne de le raconter ici où il trouve naturellement sa place.

Vers le commencement du seizième siècle, un Pérusse des Cars avait consumé sa fortune en fondations d'hôpitaux et d'autres bonne oeuvres. Afin de subvenir aux besoins de ses onéreuses créations, il avait hypothéqué la part de patrimoine que la loi lui interdisait formellement d'aliéner, sous n'importe quelle forme.

Ses dettes étaient donc nulles légalement ; mais le pieux seigneur n'entendait point rendre des créanciers confiants victimes de libéralités exagérées. En un testament admirable de piété et d'honneur il rendit compte à ses enfants de la situation, les suppliant, en vue du repos de son âme, de tenir pour bons et valables les engagements prohibés qu'il avait pris.

Ceux-ci cherchèrent à se conformer à ses désirs, mais ils rencontrèrent, pour l'exécution, une résistance opiniâtre dans la volonté des créanciers qui ne voulaient pas être payés et dans le refus des habitants d'acheter les terres qui servaient de gages aux créances. De guerre lasse, les des Cars abandonnèrent les domaines engagés, purement et simplement.

L'un de ceux-ci consistait en une vaste prairie attenant au fief de Roffignac. Pendant cent ans et plus cette prairie resta close comme lieu sacré, tabou. La cloture tomba enfin d'elle-même et l'enclos devint, par la force de l'habitude, bien communal où chacun menait, à son gré, paître son bétail ; c'était, plutôt qu'un bien communal, une prairie nullius. Elle a traversé même la révolution dans ces conditions, et ce n'est qu'après 1860 qu'elle a trouvé un acquéreur, lequel a déposé le prix d'achat dans la caisse municipale.