Search

Search our 8.352 News Items

CATEGORIES

We found 1051 books in our category 'LITERATURE'

We found 38 news items

We found 1051 books

NCOS

Brussel

1994

BEL

condition: Very Good

book number: 202503241418

Doodgraver Deernis en andere dromen

Paperback, in-8, 183 pp., illustraties, bibliografische noten, bibliografie, index/register.

"Doodgraver Deernis en andere dromen" is een verzameling van korte verhalen geschreven door Biyi Bandele-Thomas en Ellis van Midden. De verhalen zijn een mix van realiteit en fantasie, waarbij de auteurs de lezer meenemen op een reis door verschillende culturen en tijden. De verhalen zijn zowel ontroerend als humoristisch en bieden een uniek inzicht in de menselijke ervaring. De personages zijn levendig en complex, en hun verhalen zijn doordrenkt met thema's van liefde, verlies en hoop. Dit boek is een must voor iedereen die houdt van literatuur die zowel de verbeelding prikkelt als diepe emoties oproept.

"Doodgraver Deernis en andere dromen" is een verzameling van korte verhalen geschreven door Biyi Bandele-Thomas en Ellis van Midden. De verhalen zijn een mix van realiteit en fantasie, waarbij de auteurs de lezer meenemen op een reis door verschillende culturen en tijden. De verhalen zijn zowel ontroerend als humoristisch en bieden een uniek inzicht in de menselijke ervaring. De personages zijn levendig en complex, en hun verhalen zijn doordrenkt met thema's van liefde, verlies en hoop. Dit boek is een must voor iedereen die houdt van literatuur die zowel de verbeelding prikkelt als diepe emoties oproept.

'Biyi Bandele-Thomas, Ellis van Midden@ wikipedia

€ 10.00

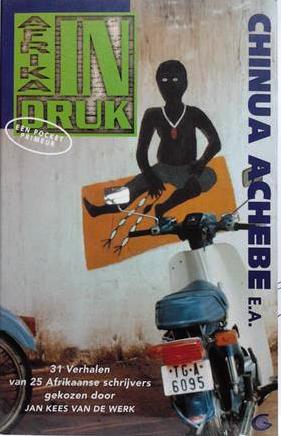

Afrika indruk. Afrikaanse verhalen samengesteld en ingeleid door Jan Kees Van de Werk

Pocket, 317 pp., met bibliografie

ACHEBE Chinua, e.a.@ wikipedia

€ 15.00

Breda

De Geus

2006

NLD

condition: Very Good

book number: 202504021531

Requiem voor een vis

Paperback, in-8, 414 pp.

Een jonge vrouw erft van haar vader wetenschappelijke onderzoeksgegevens over een prehistorische vis die de 'missing link' zou zijn tussen water- en landdieren en raakt verwikkeld in een wetenschappelijk conflict op leven en dood.

Een jonge vrouw erft van haar vader wetenschappelijke onderzoeksgegevens over een prehistorische vis die de 'missing link' zou zijn tussen water- en landdieren en raakt verwikkeld in een wetenschappelijk conflict op leven en dood.

ADAMO Christine@ wikipedia

€ 10.00

Les désirs impudiques de Lady Béatrice.

Hardcover, jaquette, relié, 8vo, 201 pp.

Le livre explore les désirs et les fantasmes de Lady Béatrice, une femme de la haute société victorienne. L'auteur nous plonge dans un univers sensuel et interdit, où les conventions sociales sont bravées et les passions secrètes sont dévoilées. Le style d'écriture est raffiné et élégant, avec des descriptions détaillées qui stimulent l'imagination du lecteur. Les personnages sont bien développés et leur complexité ajoute une profondeur à l'histoire. Ce livre est idéal pour ceux qui apprécient la littérature érotique avec une touche de sophistication.

Le livre explore les désirs et les fantasmes de Lady Béatrice, une femme de la haute société victorienne. L'auteur nous plonge dans un univers sensuel et interdit, où les conventions sociales sont bravées et les passions secrètes sont dévoilées. Le style d'écriture est raffiné et élégant, avec des descriptions détaillées qui stimulent l'imagination du lecteur. Les personnages sont bien développés et leur complexité ajoute une profondeur à l'histoire. Ce livre est idéal pour ceux qui apprécient la littérature érotique avec une touche de sophistication.

Adaptation française de Paul BRAUCA@ wikipedia

€ 10.00

Gouda

G.B. Van Goor Zonen

1878

DEU

condition: Good, cover licht beschadigd, roestvlekjes

book number: 39601

Licht en Donker in een Meisjesleven naar het Hoogduitsch van Clare Crom.

Hardcover, leder, goudopdruk op cover en rug, gebonden, 8vo,161 pp, geïllustreerd

AGATHA@ wikipedia

€ 15.00

Baarn

Ambo

1992

EGY

condition: As new/comme neuf/wie neu/als nieuw

book number: 19750117

Oorlog in het land Egypte (vertaling van Al-harb fi barr Misr - 1975)

Pb, in-8, 155 pp. Uit het Arabisch vertaald door Heleen Koesen. Dit boek, geschreven in 1975, werd in Egypte tot 1985 verboden en werd daarom eerst in Beiroet uitgegeven. Al-ka'ied (°al-Dahrieja 1944). Thema: Oktober-oorlog 1973 met Israël. Zoon van een lokale machthebber laat zich vervangen tijdens zijn legerdienst. De vader van de vervanger kan alzo zijn lapje grond behouden.

AL-KA'IED Joesef@ wikipedia

€ 7.50

Amsterdam

De bezige bij

2014

INT

condition: Very good/Très bel état/Sehr gut/Zeer goed

book number: 202408091414

Caravantis

Paperback, in-8, 304 pp.

In een fictieve Europese dwergstaat wordt tevergeefs de schijn van utopie opgehouden.

Caravantis is een spannend boek geschreven door Frank Albers. Het verhaal speelt zich af in een post-apocalyptische wereld waarin de hoofdpersoon, Caravantis, moet overleven. Het boek is een mix van sciencefiction, avontuur en politieke satire. Het boek is zeer gedetailleerd en bevat veel verrassende plotwendingen. Het is een boeiend verhaal dat de lezer van begin tot eind in zijn greep houdt.

In een fictieve Europese dwergstaat wordt tevergeefs de schijn van utopie opgehouden.

Caravantis is een spannend boek geschreven door Frank Albers. Het verhaal speelt zich af in een post-apocalyptische wereld waarin de hoofdpersoon, Caravantis, moet overleven. Het boek is een mix van sciencefiction, avontuur en politieke satire. Het boek is zeer gedetailleerd en bevat veel verrassende plotwendingen. Het is een boeiend verhaal dat de lezer van begin tot eind in zijn greep houdt.

ALBERS Frank@ wikipedia

€ 15.00

Amsterdam

Arbeiderspers

1995

USA

condition: Very good

book number: 18660009

Fatale liefdesjacht (vert. van A Long Fatal Love Chase - 1866)

Pb, in-8, 230 pp. Uit het Amerikaans vertaald door Tinke Davids. Het manuscript bleef ongepubliceerd tot 1995. Het werd in 1866 door de uitgever afgewezen als 'te vrijmoedig'. Alcott (1832-1888)

ALCOTT Louisa May@ wikipedia

€ 7.50

Amsterdam

Bert Bakker

1991

ESP

condition: Very good

book number: 19360067

Locos. Een gebarenkomedie.

Pb, in-8, 201 pp.

ALFAU Felipe@ wikipedia

€ 15.00

Spaanse Letterkunde.

Pocket, 526 pp, index

ALONSO HERNANDEZ J.L., HERMANS H.L.M., METZELIN M., OOSTENDORP H.T.@ wikipedia

€ 10.00

Berlin

Deutsche Buch-Gemeinschaft

1967

DEU

condition: Very fine

book number: 33418

Novellen und Erzählungen

Hardcover, leinen, gebunden, 8vo, 418 pp.

ANDRES Stefan@ wikipedia

€ 10.00

Antwerpen

Continental Publishing

1998

BEL

condition: Very good

book number: 38215

De Poolse Connectie.

Softcover, pb, 8vo, 127 pp.

ANDRIES Marc@ wikipedia

€ 10.00

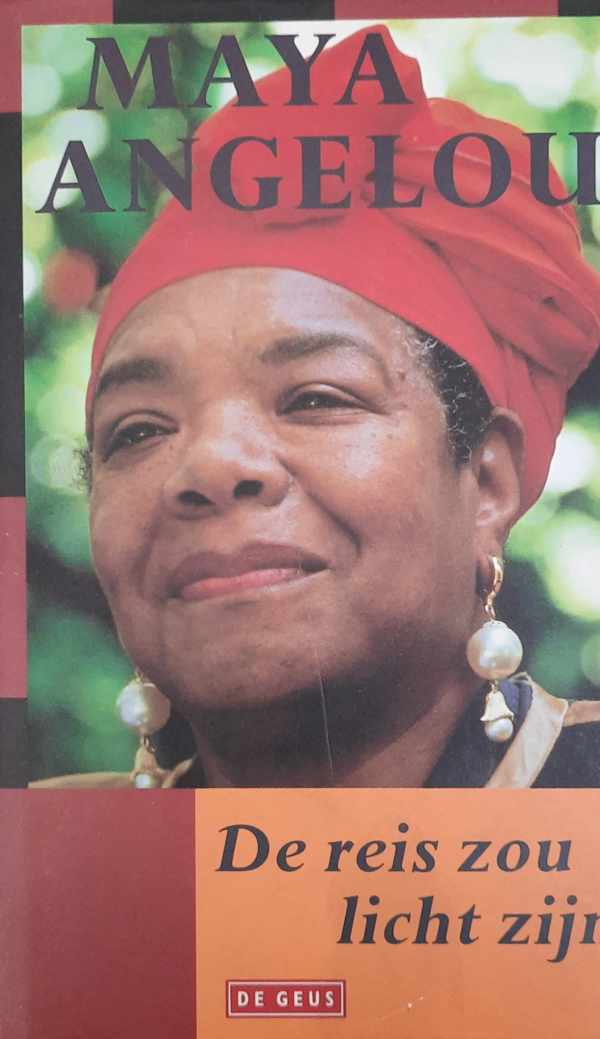

Breda

De Geus

1994

USA

condition: Very good/Très bel état/Sehr gut/Zeer goed

book number: 202209191626

De reis zou licht zijn

Hardcover, stofwikkel, in-8, 126 pp., vertaald uit het Amerikaans.

Verzameling 'levensopvattingen' over diverse onderwerpen als de voordelen van een geplande zwangerschap en confrontaties met de dood.

Maya Angelou, eigenlijk Margueritte Johnson (Saint Louis, Missouri, 4 april 1928 – Winston-Salem, 28 mei 2014), was een Amerikaans schrijver, dichter, zangeres, danseres, burgerrechtenactivist en hoogleraar amerikanistiek.

Verzameling 'levensopvattingen' over diverse onderwerpen als de voordelen van een geplande zwangerschap en confrontaties met de dood.

Maya Angelou, eigenlijk Margueritte Johnson (Saint Louis, Missouri, 4 april 1928 – Winston-Salem, 28 mei 2014), was een Amerikaans schrijver, dichter, zangeres, danseres, burgerrechtenactivist en hoogleraar amerikanistiek.

ANGELOU Maya@ wikipedia

€ 10.00

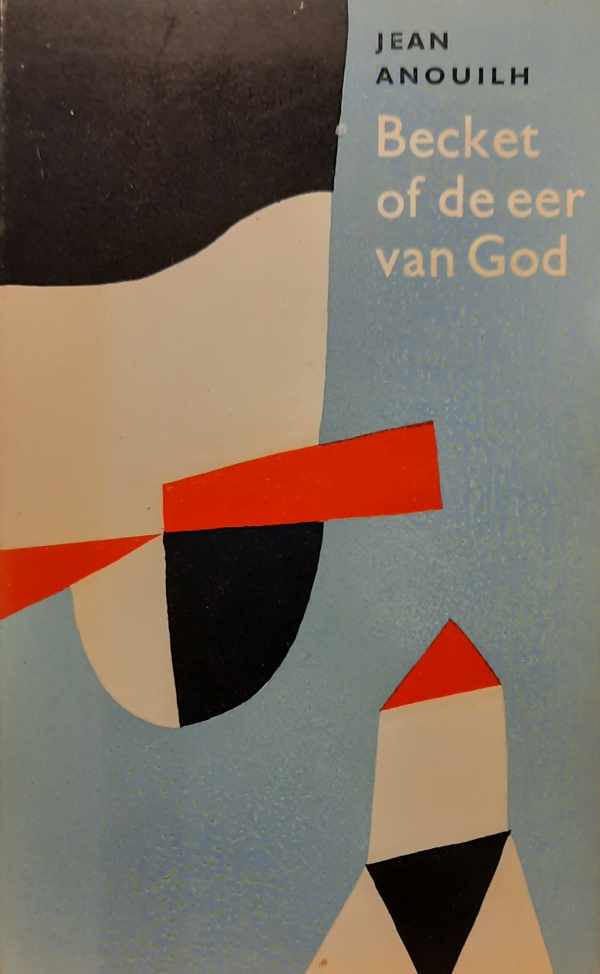

Amsterdam

De bezige bij

1960

BEL

condition: good, bon état

book number: 202403051627

Becket of de eer van God

Paperback, in-8, 171 pp.

"Becket of de eer van God" is een toneelstuk geschreven door Jean Anouilh. Het verhaal speelt zich af in de 12e eeuw en draait om de complexe relatie tussen Thomas Becket, de aartsbisschop van Canterbury, en koning Henry II van Engeland. Het stuk onderzoekt thema's als macht, vriendschap, verraad en de spanning tussen kerk en staat. Het is een diepgaande historische analyse die de aandacht van historici zou trekken, vooral degenen die geïnteresseerd zijn in de middeleeuwse geschiedenis van Engeland en de kerkstaat conflicten.

"Becket of de eer van God" is een toneelstuk geschreven door Jean Anouilh. Het verhaal speelt zich af in de 12e eeuw en draait om de complexe relatie tussen Thomas Becket, de aartsbisschop van Canterbury, en koning Henry II van Engeland. Het stuk onderzoekt thema's als macht, vriendschap, verraad en de spanning tussen kerk en staat. Het is een diepgaande historische analyse die de aandacht van historici zou trekken, vooral degenen die geïnteresseerd zijn in de middeleeuwse geschiedenis van Engeland en de kerkstaat conflicten.

ANOUILH Jean@ wikipedia

€ 7.50

Paris

Albin Michel

1977

FRA

condition: good, bon état

book number: 202403051744

Monsieur le president

Broché, in-8, 340 pp.

"Monsieur le président" est un roman écrit par l'auteur guatémaltèque Miguel Angel Asturias. Le livre est une dénonciation poignante de la tyrannie et de la corruption qui ont ravagé l'Amérique latine au XXe siècle. L'histoire est centrée sur un dictateur sans nom qui règne avec une cruauté impitoyable, utilisant la peur, la manipulation et une série de meurtres et de disparitions pour maintenir son pouvoir. Le livre est écrit dans un style lyrique et imagé, avec une utilisation intensive de la métaphore et de l'allégorie pour représenter les horreurs de la dictature. Malgré son sujet sombre, le roman est également plein d'humanité et d'humour, offrant un portrait complexe et nuancé de la vie sous un régime oppressif.

"Monsieur le président" est un roman écrit par l'auteur guatémaltèque Miguel Angel Asturias. Le livre est une dénonciation poignante de la tyrannie et de la corruption qui ont ravagé l'Amérique latine au XXe siècle. L'histoire est centrée sur un dictateur sans nom qui règne avec une cruauté impitoyable, utilisant la peur, la manipulation et une série de meurtres et de disparitions pour maintenir son pouvoir. Le livre est écrit dans un style lyrique et imagé, avec une utilisation intensive de la métaphore et de l'allégorie pour représenter les horreurs de la dictature. Malgré son sujet sombre, le roman est également plein d'humanité et d'humour, offrant un portrait complexe et nuancé de la vie sous un régime oppressif.

ASTURIAS Miguel Angel@ wikipedia

€ 10.00

Hilversum

Just Publishers

2006

GRB

condition: Very Good

book number: 202505141541

Northanger Abbey (Catherine) - DVD + boek

DVD + het boek (in-8, 301 pp.)

"Northanger Abbey" is a classic novel by Jane Austen, originally published posthumously in 1817. The story revolves around the protagonist, Catherine Morland, a young, naive woman who is fond of Gothic novels. The novel is a satirical commentary on the popular Gothic novels of the time and the misconceptions they fostered. Austen uses her sharp wit and keen observations to explore themes of love, friendship, societal expectations, and the power of imagination. The novel is set in Bath and the fictitious Northanger Abbey, where Catherine's wild imagination leads her to misconstrue ordinary events as supernatural occurrences. Austen's clever storytelling and her ability to create complex, relatable characters make "Northanger Abbey" an engaging read.

"Northanger Abbey" is a classic novel by Jane Austen, originally published posthumously in 1817. The story revolves around the protagonist, Catherine Morland, a young, naive woman who is fond of Gothic novels. The novel is a satirical commentary on the popular Gothic novels of the time and the misconceptions they fostered. Austen uses her sharp wit and keen observations to explore themes of love, friendship, societal expectations, and the power of imagination. The novel is set in Bath and the fictitious Northanger Abbey, where Catherine's wild imagination leads her to misconstrue ordinary events as supernatural occurrences. Austen's clever storytelling and her ability to create complex, relatable characters make "Northanger Abbey" an engaging read.

AUSTEN Jane@ wikipedia

€ 0.00

Hilversum

Just Publishers/BBC

2006

GBR

condition: As new/comme neuf/wie neu/als nieuw

book number: 18180004

Catherine (boek + DVD) (vertaling van Northanger Abbey - 1818)

Boek en DVD in originele slipcase. Pb, in-8, 301 pp. DVD met speelduur van 90'; formaat 4:3; Nederlandse ondertiteling. Verfilmd door BBC (1986) met Katherine Schlesinger en Peter Firth in de hoofdrollen. Peter Firth speelde eerder in 'Tess' van Polanski. GBR LITERATURE Harry 20110413 7 12,5

AUSTEN Jane@ wikipedia

€ 15.00

Amsterdam

Bezige Bij

2009

BEL

condition: Very good/Très bel état/Sehr gut/Zeer goed

book number: 202402072039

Kentucky, mijn land - roman

Pb, in-8, 157 pp.

"Kentucky, mijn land" is een roman geschreven door Paul Baeten Gronda. Het verhaal draait om een man genaamd Bobby, die na een lange tijd terugkeert naar zijn geboorteland, Kentucky. Hij wordt geconfronteerd met zijn verleden en de mensen die hij heeft achtergelaten. De roman is een diepgaande verkenning van identiteit, familiebanden en de invloed van het verleden op het heden.

"Kentucky, mijn land" is een roman geschreven door Paul Baeten Gronda. Het verhaal draait om een man genaamd Bobby, die na een lange tijd terugkeert naar zijn geboorteland, Kentucky. Hij wordt geconfronteerd met zijn verleden en de mensen die hij heeft achtergelaten. De roman is een diepgaande verkenning van identiteit, familiebanden en de invloed van het verleden op het heden.

BAETEN GRONDA Paul@ wikipedia

€ 10.00

Het mooie leven en de oorlogen van anderen. Of de avonturen van Mr. Pyle, gentleman en spion in Europa. Historische roman.

Softcover, pb, 8vo, 517 pp.

Het boek vertelt het verhaal van Mr. Pyle, een gentleman en spion, die zich in het Europa van de 19e eeuw bevindt. Tegen de achtergrond van politieke intriges, oorlogen en de veranderende sociale orde, leidt Mr. Pyle een avontuurlijk en opwindend leven. Het boek biedt een fascinerend inzicht in de geschiedenis van Europa, gezien door de ogen van een spion.

Het boek vertelt het verhaal van Mr. Pyle, een gentleman en spion, die zich in het Europa van de 19e eeuw bevindt. Tegen de achtergrond van politieke intriges, oorlogen en de veranderende sociale orde, leidt Mr. Pyle een avontuurlijk en opwindend leven. Het boek biedt een fascinerend inzicht in de geschiedenis van Europa, gezien door de ogen van een spion.

BARBERO Alessandro@ wikipedia

€ 10.00

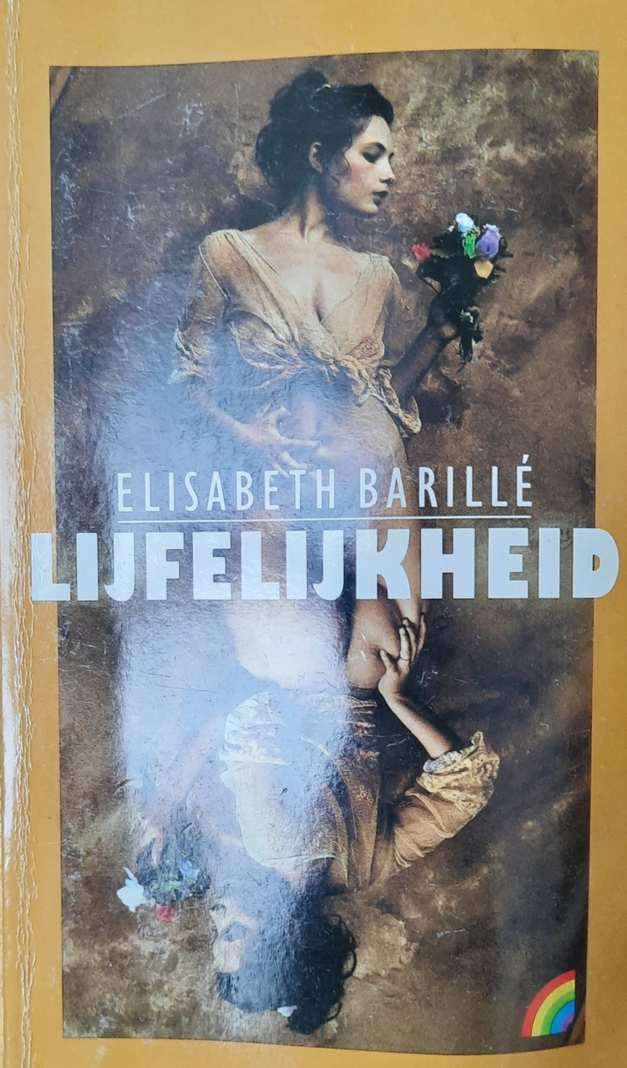

Lijfelijkheid

Pocket, 184 pp.

BARILLE Elisabeth@ wikipedia

€ 10.00

We found 38 news items

13 april 2025: Mario Vargas Llosa (1936-2025) overleden. R.I.P.

ID: 202504134242

Nobelprijs 2010

Dictionnaire amoureux de l'Amérique latine

zie zijn autobiografie, De vis in het water

Dictionnaire amoureux de l'Amérique latine

zie zijn autobiografie, De vis in het water

Land: PER

nieuw boek van Dimitri Verhulst: Bechamel Mucho

ID: 202406081151

SAMENVATTING

SAMENVATTINGZe hoefden heel even nergens in uit te blinken, niet in hun job, niet in hun sport, niet eens zoveel in het ouderschap zelfs. Het veel te kleine cadeautje van het kapitalisme was dit verlof, een doekje voor het leegbloeden, de grote schijnvertoning van de welvaart. En dus dienden ze te worden verwend.

Bechamel Mucho begint als een zonnige diavoorstelling van een zorgeloze zomer, waarbij allerhande gasten van een Spaans clubhotel de revue passeren. Maar schijn bedriegt, want al snel ontvouwt zich een scherpe en meeslepende schets van de consumptiemaatschappij. De kersverse weduwe, de alleenstaande moeder met kind, de vrouwelijke helft van een uitgeblust echtpaar, de jonge stewardess op zoek naar ontspanning, de fitte fietser, iedere gast heeft haar eigen verhaal. En allemaal willen ze, al dan niet voor een nacht, Alex, de animator van het hotel. En het is Alex die aan het einde van het seizoen moet beslissen wat hij gaat doen. Of eigenlijk: wie hij wil zijn.

Land: BEL

Jean-Baptiste Andrea wint prix Goncourt met zijn roman 'Veiller sur elle'

ID: 202311071312

Land: FRA

11 juli 2023: Milan Kundera overleden. R.I.P.

ID: 202307110082

Land: CZE

Italiaanse oorlogsromans als punten in de geschiedenis - La Storia

ID: 202304072246

•1978: Lewis (1908-2003), Naples '44

•1974: Morante (1912-1985), La Storia

•1958: Levi (1919-1987), Se questo è un uomo

•1957: Moravia (1907-1990), La Ciociara

•1952: Ginzburg (1916-1991), Tutti i nostre ieri

•1949: Malaparte (1898-1957), La Pelle

•1949: Vigano (1900-1976), L'Agnese va a morire

•1948: Pavese (1908-1950), La casa in collina

•8 mei 1945: VE-day

•1944: Malaparte (1898-1957), Kaputt

18802030

Nog voor het einde van de oorlog in Europa (VE-day) kwam de roman van Malaparta, Kaputt, op de markt. Een Italiaanse roman met een Duitse titel. Het was een niet mis te verstane boodschap aan nazi-Duitsland en aan Hitler. Malaparte wist heel goed wat een wereldoorlog betekende; hij had er twee meegemaakt; één keer aan de 'goede' kant en één keer aan de 'slechte', de 'verkeerde' kant. En die tweede keer voor de helft van de duur ervan aan de 'slechte' kant, voor de tweede helft weer aan de 'goede' kant. Genoeg redenen voor zijn cynisme en de bijtende humor.

Het Italiaans fascisme is niet ontstaan uit een 'revanche'-idee, wat in Duitsland wél het geval was.

Wie het na-oorlogse klimaat in Italië wil vatten, kan niet voorbij aan de Italiaanse cinema. Literatuur en film zijn er werelden die in elkaar overvloeien. Niemand kan voorbij aan de grote Vittorio de Sica (1894-1974) en zijn scenarist Cesare Zavattini (1902-1989). Hij had zelfs geen decors nodig. De kapotgebombardeerde wijken van Rome leverden die in al hun desolate treurnis. Het neorealisme bracht puike films met de gewone man als hoofdvertolker.

Ladri di Biciclette - 1948

Land: ITA

Dictators, ideologieën, Italiaanse schrijvers en de oorlogen

ID: 202304020348

RANGE 1880-2030

Antonio PENNACCHI

WW2

NAZISM

FASCISM

Primo LEVI

COMMUNISM

WW1

Elsa MORANTE

Cesare PAVESE

Alberto MORAVIA

Curzio MALAPARTE

FRANCO

SALAZAR

HITLER

MUSSOLINI

STALIN

RANGE 1880-2030

Land: ITA

Annie Ernaux wint de Nobelprijs literatuur

ID: 202210070121

Land: FRA

Moravia over oorlog

ID: 202204130037

Moravia over oorlog

"Ik bedacht dat oorlog (...) nu eenmaal oorlog was en dat in een oorlog altijd de besten verloren gaan omdat zij het moedigst, het onzelfzuchtigst en het eerlijkst zijn; sommigen werden vermoord (...) en anderen voor de rest van hun leven in het ongeluk gestort (...). De slechtste mensen daarentegen, zij die geen moed hebben, geen geloof, geen idealen, geen trots, zij die moorden en stelen en slechts aan zichzelf denken en alleen eigenbelang op het oog hebben, zij zijn degenen die er veilig doorheen komen, wie het voor de wind gaat en ze worden zelfs nog brutaler en verdorvener dan voorheen."

Moravia, La Ciociara, 1957, p. 304

"Ik bedacht dat oorlog (...) nu eenmaal oorlog was en dat in een oorlog altijd de besten verloren gaan omdat zij het moedigst, het onzelfzuchtigst en het eerlijkst zijn; sommigen werden vermoord (...) en anderen voor de rest van hun leven in het ongeluk gestort (...). De slechtste mensen daarentegen, zij die geen moed hebben, geen geloof, geen idealen, geen trots, zij die moorden en stelen en slechts aan zichzelf denken en alleen eigenbelang op het oog hebben, zij zijn degenen die er veilig doorheen komen, wie het voor de wind gaat en ze worden zelfs nog brutaler en verdorvener dan voorheen."

Moravia, La Ciociara, 1957, p. 304

Land: ITA

Colonial Impotence. Virtue and Violence in a Congolese Concession (1911–1940)

ID: 202109161519

•

Verschenen bij De Gruyter

About this book

In Colonial Impotence, Benoît Henriet studies the violent contradictions of colonial rule from the standpoint of the Leverville concession, Belgian Congo’s largest palm oil exploitation. Leverville was imagined as a benevolent tropical utopia, whose Congolese workers would be "civilized" through a paternalist machinery. However, the concession was marred by inefficiency, endemic corruption and intrinsic brutality. Colonial agents in the field could be seen as impotent, for they were both unable and unwilling to perform as expected. This book offers a new take on the joint experience of colonialism and capitalism in Southwest Congo, and sheds light on their impact on local environments, bodies, societies and cosmogonies.

Author information

Benoît Henriet, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium.

Reviews

"This is a major contribution to the historiography of colonial central Africa and the growing literature on the concessionary model used in many different colonial contexts." – Jeremy Rich, Professor of History, Marywood University

"This compelling book unveils the importance of hubris and self-deception in the deployment of colonial capitalism. Henriet recreates Leverville as a capitalistic site and a matrix of emotions and affects, of virtuous excesses and moral failures. His concept of 'impotence,' broadly conceptualized as a sexual, social, political, and economic formation, is an important addition to our knowledge of relations of power in the colony." – Florence Bernault, Centre d'histoire, Sciences Po (Paris)

Verschenen bij De Gruyter

About this book

In Colonial Impotence, Benoît Henriet studies the violent contradictions of colonial rule from the standpoint of the Leverville concession, Belgian Congo’s largest palm oil exploitation. Leverville was imagined as a benevolent tropical utopia, whose Congolese workers would be "civilized" through a paternalist machinery. However, the concession was marred by inefficiency, endemic corruption and intrinsic brutality. Colonial agents in the field could be seen as impotent, for they were both unable and unwilling to perform as expected. This book offers a new take on the joint experience of colonialism and capitalism in Southwest Congo, and sheds light on their impact on local environments, bodies, societies and cosmogonies.

Author information

Benoît Henriet, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Belgium.

Reviews

"This is a major contribution to the historiography of colonial central Africa and the growing literature on the concessionary model used in many different colonial contexts." – Jeremy Rich, Professor of History, Marywood University

"This compelling book unveils the importance of hubris and self-deception in the deployment of colonial capitalism. Henriet recreates Leverville as a capitalistic site and a matrix of emotions and affects, of virtuous excesses and moral failures. His concept of 'impotence,' broadly conceptualized as a sexual, social, political, and economic formation, is an important addition to our knowledge of relations of power in the colony." – Florence Bernault, Centre d'histoire, Sciences Po (Paris)

Elsa Morante in other languages in: New Italian Books

ID: 202107125529

12 July 2021

Author: Monica Zanardo, University of Padova

Elsa Morante in other languages in: New Italian Books

The international success of the books of Elsa Morante (1912-1985) more or less mirrors her publishing success and popularity in Italy. After the lukewarm reception of Menzogna e sortilegio (1948), L’isola di Arturo (1957) was immediately successful, thanks also to its being awarded the prestigious Strega Prize, which also gave her greater visibility abroad. Her standing abroad was further enhanced after the publication of La Storia (1974), which was successful in terms of both popularity and sales, paving the way for her penetration of the European book market with her last novel, Aracoeli (1982). This success also contributed (though to a lesser extent) towards the rediscovery of her debut novel, which remains, however, Morante’s least translated book.

There were only two translations of Menzogna e sortilegio in the 1950s: the American edition published in 1951 and the German edition published in Zürich in 1952. This edition, translated by Hanneliese Hinderberger (who would later also translate La Storia in 1976), was subsequently published by the prestigious Suhrkamp Verlag (from 1981), with an afterword by Dominique Fernandez. There was a totally different reaction to her book in America, translated by Adrienne Foulke, with the editorial assistance of Andrew Chiappe, and published by Harcourt Brace following the intervention of William Weaver. Published under the title House of Liars, the book was a total failure. Morante was very unhappy with the translation, not just because of the many inaccuracies, but, above all, because of the major cuts imposed on her novel, which was abridged by almost 20%. After almost 70 years, a new translation is planned for The New York Review of Books. Menzogna e sortilegio is still today the least translated of Morante’s novels, even less translated than the collection of short stories Lo scialle andaluso. The novel was only rediscovered after L’isola di Arturo (the novel which brought her domestic fame and opened the door for her in many parts of Europe) was translated into French in 1967 (by Michel Arnaud, but with significant editing for Gallimard’s prestigious “Du monde entier” series) and Polish in 1968 (by Zofia Ernstowa, with the poetic inserts entrusted to Jerzy Kierst). Only after the author’s death was the book published in Danish (1988, translated by Jytte Lollesgaard), Hebrew (2000, translated by Miryam Shusṭ erman-Padovano) and Spanish (2012, translated by Ana Ciurans Ferrándiz, and republished in 2017 with a foreword by Juan Tallón). In 2019, the publishers Kastaniotis announced the imminent release of a translation into Greek, while translations are also underway into Dutch (as part of a larger publishing project to publish all of Morante’s novels being carried out by Wereldbibliotheek) and Macedonian. The reception of Morante’s works in the Balkans is rather different, however, as the first of her novels to be published in that region was, in fact, Menzogna e sortilegio (published in Yugoslavia, in 1972, in Serbo-Croatian, in its Cyrillic version by Miodrag Kujundzić and Ivanka Jovičić), with the rediscovery much later of Isola di Arturo and La Storia (both were published in 1987, in, respectively, Serbia, translated by Jasmina Livada, and Bosnia, translated by Razija Sarajilić), and, in 1989, of Lo Scialle andaluso (published by the Serbian publishing house Gradina and translated by Ana Srbinović and Elizabet Vasiljević).

The international success of L’isola di Arturo [Arturo’s Island] was more straightforward, with the book translated into fourteen languages within ten years of its publication in Italy. It was almost immediately available in Scandinavia, with the Finnish translation published in 1958 (Alli Holma) and the Swedish translation (Karin Alin) and Norwegian translation (Hans Braarving) in the following year. Between 1959 and 1960, the book was also translated into German (Susanne Hurni-Maehler, who, in 1985, also retranslated Lo scialle andaluso, the first German version of which, translated by Kurt Stoessel, was published in Switzerland in 1960), into English (by Isabel Quigly for Collins, with a new translation in 2019 by Ann Goldstein, the American translator of Elena Ferrante, who also has in the pipeline a new translation of La Storia [History: A Novel]), into Spanish (Eugenio Guasta in Argentina, with a version published in Catalan, translated by Joan Oliver, in 1965), into Polish (Barbara Sieroszewska) and Dutch (J.H. Klinkert-Pötters Vos). During the 1960s translations were also published in French (in 1963, Michel Arnaud, who subsequently also translated Menzogna e sortilegio in 1967 and La Storia in 1977, while her collection of short stories Lo scialle andaluso were translated by Mario Fusco), in Japanese (Teruo Ōkubo), in Hungarian (Éva Dankó), in Portuguese (Hermes Serrão in 1966, with a new translation by Loredana de Stauber Caprara and Regina Célia Silva published by the Brazilian publishing house Berlendis & Vertecchia in 2003), in Romanian (Constantin Ioncică – still Morante’s only book to be translated into Romanian, though there should soon be available a translation of La Storia), in Korean (1989), in Macedonian (2017, Nenad Trpovski), in Turkish (2007, Şadan Karadeniz, who ten years earlier had also translated Lo scialle andaluso) and in Albanian (2019, Shtëpia Botuese). Translations of L’isola di Arturo are currently underway into Georgian and Czech, while Morante’s first book to be published in Lithuanian will also be L’isola di Arturo (Alma Littera).

Morante’s first book to be published in Denmark was La Storia (1977), translated by Jytte Lollesgard, who went on to complete the translations of all Morante’s novels into Danish (L’isola di Arturo in 1984, and Menzogna e sortilegio and Aracoeli, both published in 1988), as well as her collection of short stories Le straordinarie avventure di Caterina (1989). In Slovenia, the international success of La Storia curiously led to L’Isola di Arturo being rediscovered (1976, translated by Cvetka Žužek-Granata), while Aracoeli (1993) and La Storia (2006), translated respectively by Srečko Fišer and Dean Rajčić, did not appear until after the author’s death.

Two translations of La Storia deserve a special mention: the American translation, because it was followed closely by Morante, and the Spanish translation, because of the controversy it caused. In America, the book was translated by William Weaver and published by the Franklin Library First Edition Society, with an invaluable preface by Morante, who negotiated with her literary agent Erich Linder for the punctuation in the book’s English title. The Spanish edition (1976, translated by Juan Moreno), on the other hand, was publicly criticised by the author, who accused the publishers Plaza y Janés of having censored her book, though an uncensored version of the book did not become available in Spanish (translated by Esther Benitez) until 1991. This translation was subsequently revised in 2008 by Flavia Cartoni, who also wrote a foreword to the novel.

Before the author’s death, La Storia was translated into twelve languages (in addition to the English and Spanish versions, there were also translations into French, German, Portuguese, Dutch, Finnish, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Japanese and Chinese), with the book translated into another five languages by the end of the 1990s (Serbian, Czech, Hebrew, Turkish and Greek). Other languages have been added during the last twenty years, including Russian, Hungarian and Macedonian, but also Persian and Slovak (with La Storia being Morante’s only work to be published in these two languages in, respectively, 2003 and 2010). Curiously, the book has not been translated into Polish, but it has been recently translated (or is being translated) into Albanian, Rumanian, and even Arabic and Georgian.

Despite Morante’s well-established international reputation, Aracoeli did not achieve the same international reach. In 1984, the novel was translated into English, Spanish, German, Norwegian and French (by Jean-Noël Schifano, with the novel awarded the prestigious Prix Médicis étrangers) and, in 1985, into Swedish. Not until after her death was the novel also published in Finnish (1987), Danish and Czech (1988, when the Czech translation of La Storia was also published) and Slovene (1993). Aracoeli was Morante’s first work to be translated into both Greek and Hebrew. In Israel the translation of Aracoeli (1989, Miryam Shusṭ erman-Padovano) was followed, in 1994, by Lo scialle andaluso (Orah Ayal) and, going backwards, Morante’s other novels (La Storia, translated in 1995 by ʻImanuʼel Beʼeri; L’isola di Arturo and Menzogna e sortilegio, both translated by Miryam Shusṭ erman-Padovano and published in, respectively, 1997 and 2000). In Greece, the translation of Aracoeli (1989) paved the way for a very positive reception of Morante’s work and, in addition to the translations of her major novels and collections of short stories, there is one of the very rare translations of Il mondo salvato dai ragazzini (1996) and of the even less translated Lettere ad Antonio (published posthumously in Italy, edited by Alba Andreini, with title Diario 1938), which, besides Greek, can only be read in German and French.

Less successful, but nevertheless satisfactory, was the publication internationally of her collection of short stories Lo scialle andaluso (which have still not been translated into English), which were almost immediately translated into French and German, and then, during the 1980s, into Turkish, Estonian and Serbian. They can now also be read in Hebrew, Dutch, Spanish, Japanese, Albanian and Russian (the stories from Lo scialle andaluso and La Storia are Morante’s only works to be translated into Russian). They will soon be published in Portuguese, too. There are fewer translations of her short stories that were published posthumously. Racconti dimenticati have been translated into German, Greek, French and Dutch (in Dutch these short stories were published together with those from Lo scialle andaluso), with a Hebrew version currently underway; while Aneddoti infantili have only been translated into French (2015, Claire Pellissier). The collection of short stories for children, Straordinarie avventure di Caterina, have been fairly successful, however. They were translated almost immediately into Japanese and Hungarian, and, after the author’s death and during the 1990s, into French, Swedish, Danish, Spanish, Norwegian and German.

There are very few translations, however, of Alibi, the short collection of poems published by Longanesi in 1958. It was translated into French in 1999 (Jean-Noël Schifano, in a bilingual edition) and into Dutch in 2012 (Jan van der Haar, with the original and translation on opposite pages and a postword by Gandolfo Cascio, who was awarded the Morante Prize in 2016 for promoting Morante’s work in the Netherlands). Some individual poems have been translated, usually in magazines, as in the case of the poem that gives its name to the collection, which was translated into Polish in 1989 by Konstanty Jeleński, a friend of the author. Equally unsuccessful, partly because of the unusual form of the poems and their linguistic and conceptual complexity, and partly because they did not appeal to readers, is Il mondo salvato dai ragazzini (1968), which can only be read in French, Greek and English.

As for her literary and political writings, scant attention has been paid to Piccolo manifesto dei Comunisti (translated solely into French) and her sundry writings collected by Cesare Garboli in Pro o contro la bomba atomica e altri scritti, which can be read in German, French, Swedish, Spanish and Polish, and are currently being translated in Brazil. Her essay Sul Romanzo has been translated into Swedish, while her writings on Beato Angelico had already been translated in the 1970s.

While Elsa Morante’s minor works and poetry have a limited audience internationally, her novels, after she was awarded the prestigious Strega Prize and thanks also to the hard work of her literary agent Erich Linder, have received the attention they deserve (above all in France, Germany and Scandinavia, where they continue to be of interest). Moreover, following the author’s death, there have been publication projects in countries such as Israel, Greece and the Netherlands, to publish her complete works, some of which are nearing completion. The translation licences, some of which have been granted quite recently, confirm the continuing popularity of one of the most representative – and most represented – voices of twentieth-century Italian literature, with at least one of her works being translated into more than thirty language and whose books are distributed in all five continents.

Author: Monica Zanardo, University of Padova

Elsa Morante in other languages in: New Italian Books

The international success of the books of Elsa Morante (1912-1985) more or less mirrors her publishing success and popularity in Italy. After the lukewarm reception of Menzogna e sortilegio (1948), L’isola di Arturo (1957) was immediately successful, thanks also to its being awarded the prestigious Strega Prize, which also gave her greater visibility abroad. Her standing abroad was further enhanced after the publication of La Storia (1974), which was successful in terms of both popularity and sales, paving the way for her penetration of the European book market with her last novel, Aracoeli (1982). This success also contributed (though to a lesser extent) towards the rediscovery of her debut novel, which remains, however, Morante’s least translated book.

There were only two translations of Menzogna e sortilegio in the 1950s: the American edition published in 1951 and the German edition published in Zürich in 1952. This edition, translated by Hanneliese Hinderberger (who would later also translate La Storia in 1976), was subsequently published by the prestigious Suhrkamp Verlag (from 1981), with an afterword by Dominique Fernandez. There was a totally different reaction to her book in America, translated by Adrienne Foulke, with the editorial assistance of Andrew Chiappe, and published by Harcourt Brace following the intervention of William Weaver. Published under the title House of Liars, the book was a total failure. Morante was very unhappy with the translation, not just because of the many inaccuracies, but, above all, because of the major cuts imposed on her novel, which was abridged by almost 20%. After almost 70 years, a new translation is planned for The New York Review of Books. Menzogna e sortilegio is still today the least translated of Morante’s novels, even less translated than the collection of short stories Lo scialle andaluso. The novel was only rediscovered after L’isola di Arturo (the novel which brought her domestic fame and opened the door for her in many parts of Europe) was translated into French in 1967 (by Michel Arnaud, but with significant editing for Gallimard’s prestigious “Du monde entier” series) and Polish in 1968 (by Zofia Ernstowa, with the poetic inserts entrusted to Jerzy Kierst). Only after the author’s death was the book published in Danish (1988, translated by Jytte Lollesgaard), Hebrew (2000, translated by Miryam Shusṭ erman-Padovano) and Spanish (2012, translated by Ana Ciurans Ferrándiz, and republished in 2017 with a foreword by Juan Tallón). In 2019, the publishers Kastaniotis announced the imminent release of a translation into Greek, while translations are also underway into Dutch (as part of a larger publishing project to publish all of Morante’s novels being carried out by Wereldbibliotheek) and Macedonian. The reception of Morante’s works in the Balkans is rather different, however, as the first of her novels to be published in that region was, in fact, Menzogna e sortilegio (published in Yugoslavia, in 1972, in Serbo-Croatian, in its Cyrillic version by Miodrag Kujundzić and Ivanka Jovičić), with the rediscovery much later of Isola di Arturo and La Storia (both were published in 1987, in, respectively, Serbia, translated by Jasmina Livada, and Bosnia, translated by Razija Sarajilić), and, in 1989, of Lo Scialle andaluso (published by the Serbian publishing house Gradina and translated by Ana Srbinović and Elizabet Vasiljević).

The international success of L’isola di Arturo [Arturo’s Island] was more straightforward, with the book translated into fourteen languages within ten years of its publication in Italy. It was almost immediately available in Scandinavia, with the Finnish translation published in 1958 (Alli Holma) and the Swedish translation (Karin Alin) and Norwegian translation (Hans Braarving) in the following year. Between 1959 and 1960, the book was also translated into German (Susanne Hurni-Maehler, who, in 1985, also retranslated Lo scialle andaluso, the first German version of which, translated by Kurt Stoessel, was published in Switzerland in 1960), into English (by Isabel Quigly for Collins, with a new translation in 2019 by Ann Goldstein, the American translator of Elena Ferrante, who also has in the pipeline a new translation of La Storia [History: A Novel]), into Spanish (Eugenio Guasta in Argentina, with a version published in Catalan, translated by Joan Oliver, in 1965), into Polish (Barbara Sieroszewska) and Dutch (J.H. Klinkert-Pötters Vos). During the 1960s translations were also published in French (in 1963, Michel Arnaud, who subsequently also translated Menzogna e sortilegio in 1967 and La Storia in 1977, while her collection of short stories Lo scialle andaluso were translated by Mario Fusco), in Japanese (Teruo Ōkubo), in Hungarian (Éva Dankó), in Portuguese (Hermes Serrão in 1966, with a new translation by Loredana de Stauber Caprara and Regina Célia Silva published by the Brazilian publishing house Berlendis & Vertecchia in 2003), in Romanian (Constantin Ioncică – still Morante’s only book to be translated into Romanian, though there should soon be available a translation of La Storia), in Korean (1989), in Macedonian (2017, Nenad Trpovski), in Turkish (2007, Şadan Karadeniz, who ten years earlier had also translated Lo scialle andaluso) and in Albanian (2019, Shtëpia Botuese). Translations of L’isola di Arturo are currently underway into Georgian and Czech, while Morante’s first book to be published in Lithuanian will also be L’isola di Arturo (Alma Littera).

Morante’s first book to be published in Denmark was La Storia (1977), translated by Jytte Lollesgard, who went on to complete the translations of all Morante’s novels into Danish (L’isola di Arturo in 1984, and Menzogna e sortilegio and Aracoeli, both published in 1988), as well as her collection of short stories Le straordinarie avventure di Caterina (1989). In Slovenia, the international success of La Storia curiously led to L’Isola di Arturo being rediscovered (1976, translated by Cvetka Žužek-Granata), while Aracoeli (1993) and La Storia (2006), translated respectively by Srečko Fišer and Dean Rajčić, did not appear until after the author’s death.

Two translations of La Storia deserve a special mention: the American translation, because it was followed closely by Morante, and the Spanish translation, because of the controversy it caused. In America, the book was translated by William Weaver and published by the Franklin Library First Edition Society, with an invaluable preface by Morante, who negotiated with her literary agent Erich Linder for the punctuation in the book’s English title. The Spanish edition (1976, translated by Juan Moreno), on the other hand, was publicly criticised by the author, who accused the publishers Plaza y Janés of having censored her book, though an uncensored version of the book did not become available in Spanish (translated by Esther Benitez) until 1991. This translation was subsequently revised in 2008 by Flavia Cartoni, who also wrote a foreword to the novel.

Before the author’s death, La Storia was translated into twelve languages (in addition to the English and Spanish versions, there were also translations into French, German, Portuguese, Dutch, Finnish, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Japanese and Chinese), with the book translated into another five languages by the end of the 1990s (Serbian, Czech, Hebrew, Turkish and Greek). Other languages have been added during the last twenty years, including Russian, Hungarian and Macedonian, but also Persian and Slovak (with La Storia being Morante’s only work to be published in these two languages in, respectively, 2003 and 2010). Curiously, the book has not been translated into Polish, but it has been recently translated (or is being translated) into Albanian, Rumanian, and even Arabic and Georgian.

Despite Morante’s well-established international reputation, Aracoeli did not achieve the same international reach. In 1984, the novel was translated into English, Spanish, German, Norwegian and French (by Jean-Noël Schifano, with the novel awarded the prestigious Prix Médicis étrangers) and, in 1985, into Swedish. Not until after her death was the novel also published in Finnish (1987), Danish and Czech (1988, when the Czech translation of La Storia was also published) and Slovene (1993). Aracoeli was Morante’s first work to be translated into both Greek and Hebrew. In Israel the translation of Aracoeli (1989, Miryam Shusṭ erman-Padovano) was followed, in 1994, by Lo scialle andaluso (Orah Ayal) and, going backwards, Morante’s other novels (La Storia, translated in 1995 by ʻImanuʼel Beʼeri; L’isola di Arturo and Menzogna e sortilegio, both translated by Miryam Shusṭ erman-Padovano and published in, respectively, 1997 and 2000). In Greece, the translation of Aracoeli (1989) paved the way for a very positive reception of Morante’s work and, in addition to the translations of her major novels and collections of short stories, there is one of the very rare translations of Il mondo salvato dai ragazzini (1996) and of the even less translated Lettere ad Antonio (published posthumously in Italy, edited by Alba Andreini, with title Diario 1938), which, besides Greek, can only be read in German and French.

Less successful, but nevertheless satisfactory, was the publication internationally of her collection of short stories Lo scialle andaluso (which have still not been translated into English), which were almost immediately translated into French and German, and then, during the 1980s, into Turkish, Estonian and Serbian. They can now also be read in Hebrew, Dutch, Spanish, Japanese, Albanian and Russian (the stories from Lo scialle andaluso and La Storia are Morante’s only works to be translated into Russian). They will soon be published in Portuguese, too. There are fewer translations of her short stories that were published posthumously. Racconti dimenticati have been translated into German, Greek, French and Dutch (in Dutch these short stories were published together with those from Lo scialle andaluso), with a Hebrew version currently underway; while Aneddoti infantili have only been translated into French (2015, Claire Pellissier). The collection of short stories for children, Straordinarie avventure di Caterina, have been fairly successful, however. They were translated almost immediately into Japanese and Hungarian, and, after the author’s death and during the 1990s, into French, Swedish, Danish, Spanish, Norwegian and German.

There are very few translations, however, of Alibi, the short collection of poems published by Longanesi in 1958. It was translated into French in 1999 (Jean-Noël Schifano, in a bilingual edition) and into Dutch in 2012 (Jan van der Haar, with the original and translation on opposite pages and a postword by Gandolfo Cascio, who was awarded the Morante Prize in 2016 for promoting Morante’s work in the Netherlands). Some individual poems have been translated, usually in magazines, as in the case of the poem that gives its name to the collection, which was translated into Polish in 1989 by Konstanty Jeleński, a friend of the author. Equally unsuccessful, partly because of the unusual form of the poems and their linguistic and conceptual complexity, and partly because they did not appeal to readers, is Il mondo salvato dai ragazzini (1968), which can only be read in French, Greek and English.

As for her literary and political writings, scant attention has been paid to Piccolo manifesto dei Comunisti (translated solely into French) and her sundry writings collected by Cesare Garboli in Pro o contro la bomba atomica e altri scritti, which can be read in German, French, Swedish, Spanish and Polish, and are currently being translated in Brazil. Her essay Sul Romanzo has been translated into Swedish, while her writings on Beato Angelico had already been translated in the 1970s.

While Elsa Morante’s minor works and poetry have a limited audience internationally, her novels, after she was awarded the prestigious Strega Prize and thanks also to the hard work of her literary agent Erich Linder, have received the attention they deserve (above all in France, Germany and Scandinavia, where they continue to be of interest). Moreover, following the author’s death, there have been publication projects in countries such as Israel, Greece and the Netherlands, to publish her complete works, some of which are nearing completion. The translation licences, some of which have been granted quite recently, confirm the continuing popularity of one of the most representative – and most represented – voices of twentieth-century Italian literature, with at least one of her works being translated into more than thirty language and whose books are distributed in all five continents.

Land: ITA

Emanuele Trevi wint met 'Due vite' de Premio Strega literatuurprijs

ID: 202107082297

Land: ITA

29 april 2021: schrijver en vrijdenker Hafid Bouazza (1970-2021) overleden te Amsterdam. R.I.P.

ID: 202104294478

Hafid Bouazza (Oujda, 8 maart 1970 – Amsterdam, 29 april 2021) was een Marokkaans-Nederlandse schrijver.

Hafid Bouazza is geboren in Oujda aan de Marokkaans-Algerijnse grens. Het gezin kwam in oktober 1977 naar Nederland, waar de kinderen opgroeiden in Arkel. Bouazza heeft in Amsterdam de studie Arabische taal- en letterkunde gevolgd. Daarna schreef hij verschillende boeken.

Bouazza behoorde samen met Moses Isegawa en Abdelkader Benali tot de belangrijkste vertegenwoordigers van de zogeheten 'migrantenliteratuur'. Hij stond voorts bekend om zijn kritiek op de islam. Bouazza publiceerde onder meer vertaalde poëzie op het weblog Loor Schrijft.

In 2003 was Bouazza een van de gasten in het programma Zomergasten. Dat jaar won ook hij de Amsterdamprijs voor de Kunst. In 2004 won hij De Gouden Uil voor zijn roman Paravion.

In 2014 huldigde vrijdenkersvereniging De Vrije Gedachte hem als "Vrijdenker van het Jaar".

In 2014 huldigde vrijdenkersvereniging De Vrije Gedachte hem als "Vrijdenker van het Jaar".

Bouazza kampte met verschillende verslavingen en werd meermalen opgenomen in het ziekenhuis met leverfalen. Hij overleed op 51-jarige leeftijd in het OLVG-ziekenhuis in Amsterdam.

(bron: wiki)

Hafid Bouazza is geboren in Oujda aan de Marokkaans-Algerijnse grens. Het gezin kwam in oktober 1977 naar Nederland, waar de kinderen opgroeiden in Arkel. Bouazza heeft in Amsterdam de studie Arabische taal- en letterkunde gevolgd. Daarna schreef hij verschillende boeken.

Bouazza behoorde samen met Moses Isegawa en Abdelkader Benali tot de belangrijkste vertegenwoordigers van de zogeheten 'migrantenliteratuur'. Hij stond voorts bekend om zijn kritiek op de islam. Bouazza publiceerde onder meer vertaalde poëzie op het weblog Loor Schrijft.

In 2003 was Bouazza een van de gasten in het programma Zomergasten. Dat jaar won ook hij de Amsterdamprijs voor de Kunst. In 2004 won hij De Gouden Uil voor zijn roman Paravion.

In 2014 huldigde vrijdenkersvereniging De Vrije Gedachte hem als "Vrijdenker van het Jaar".

In 2014 huldigde vrijdenkersvereniging De Vrije Gedachte hem als "Vrijdenker van het Jaar".Bouazza kampte met verschillende verslavingen en werd meermalen opgenomen in het ziekenhuis met leverfalen. Hij overleed op 51-jarige leeftijd in het OLVG-ziekenhuis in Amsterdam.

(bron: wiki)

verschenen bij Arbeiderspers: Wolfstijd, Duitsland en de Duitsers 1945-1955 - Harald Jähner

ID: 202102031319

Aantal bladzijden: 503

Prijs: € 34.99

wiki:

Harald Jähner (born March 26, 1953) is a German journalist and author. Since 2011 he has been an honorary professor of cultural journalism at the Berlin University of the Arts.

Biography

Jähner studied literature, history and art history in Freiburg and completed his doctorate in Berlin. After graduation, he worked as a freelance journalist. From 1989 to 1997 Jähner was head of the communication department of the House of World Cultures in Berlin. At the same time from 1994 to 1997 he wrote as a freelance literary critic for the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. He then worked as an editor at the Berliner Zeitung, where he headed the Feuilleton department from 2003 to 2015. Since 2011, Jähner has been honorary professor of cultural journalism at Berlin University of the Arts.[1] In 2019, Jähner published Wolfszeit, a consideration of German life in the post-war decade 1945–1955,[2] published by Rowohlt Berlin.[3][4][5]

Awards

Prize of the Leipzig Book Fair 2019 – The winners from left: Eva Ruth Wenne (translation), Anke Stelling (fiction) and Harald Jähner (non-fiction book)

In 2019, Jähner won the Leipzig Book Fair Prize for Wolfszeit (Category: Non-fiction book / Essay writing)[6]

Duitsland in spiegelbeeld

Land: DEU

Premio Strega - Winnaars 1947-2024

ID: 202012328972

Premio Strega

De Premio Strega is de meest prestigieuze Italiaanse literatuurprijs. De prijs wordt sinds 1947 jaarlijks uitgereikt aan het beste fictieboek van een Italiaanse auteur en voor het eerst uitgegeven tussen 1 mei van het vorige jaar en 30 april.

Geschiedenis en selectieprocedure

In 1944 organiseerden Maria en Goffredo Bellonci voor het eerst een literair salon in hun huis in Rome. Deze zondagse bijeenkomsten bevatten al snel de meest notabele personen uit het Italiaanse culturele leven. De groep stond bekend onder de naam Amici della Domenica, de Zondagse vrienden. In 1947 besloten de Belloncis, samen met Guido Alberti, de eigenaar van het bedrijf dat Strega (likeur) produceert, om een literatuurprijs in het leven te roepen, voor het beste Italiaanse fictieboek van het vorige jaar. De winnaar wordt gekozen door de Zondagse vrienden.

Sinds de dood van Maria Bellonci in 1986 werd de organisatie overgenomen door de Fondazione Maria e Goffredo Bellonci. De leden van de vierhonderdkoppige jury worden nog steeds de Zondagse vrienden genoemd. Om een boek in aanmerking te brengen moeten ten minste twee Vrienden hiermee akkoord gaan. De lange lijst met mogelijke winnaars wordt dan uitgedund tot vijf overblijvers. De tweede stemronde, gevolgd door de proclamatie, vindt plaats op de eerste donderdag van juli in het nymphaeum van Villa Giulia in Rome.

In 2006, de zeventigste editie van de Premio Strega, werd een speciale prijs uitgereikt aan de Italiaanse Grondwet, die werd opgetekend in de beginjaren van deze literatuurprijs. De prijs werd in ontvangst genomen door voormalig president van de Italiaanse Republiek Oscar Luigi Scalfaro.

Winnaars

1947 - Ennio Flaiano, Tempo di uccidere

1948 - Vincenzo Cardarelli, Villa Tarantola

1949 - Giambattista Angioletti, La memoria

1950 - Cesare Pavese, La bella estate

1951 - Corrado Alvaro, Quasi una vita

1952 - Alberto Moravia, I racconti

1953 - Massimo Bontempelli, L'amante fedele

1954 - Mario Soldati, Lettere da Capri

1955 - Giovanni Comisso, Un gatto attraversa la strada

1956 - Giorgio Bassani, Cinque storie ferraresi

1957 - Elsa Morante, L'isola di Arturo

1958 - Dino Buzzati, Sessanta racconti

1959 - Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, Il gattopardo

1960 - Carlo Cassola, La ragazza di Bube

1961 - Raffaele La Capria, Ferito a morte

1962 - Mario Tobino, Il clandestino

1963 - Natalia Ginzburg, Lessico famigliare

1964 - Giovanni Arpino, L'ombra delle colline

1965 - Paolo Volponi, La macchina mondiale

1966 - Michele Prisco, Una spirale di nebbia

1967 - Anna Maria Ortese, Poveri e semplici

1968 - Alberto Bevilacqua, L'occhio del gatto

1969 - Lalla Romano, Le parole tra noi leggere

1970 - Guido Piovene, Le stelle fredde

1971 - Raffaello Brignetti, La spiaggia d'oro

1972 - Giuseppe Dessì, Paese d'ombre

1973 - Manlio Cancogni, Allegri, gioventù

1974 - Guglielmo Petroni, La morte del fiume

1975 - Tommaso Landolfi, A caso

1976 - Fausta Cialente, Le quattro ragazze Wieselberger

1977 - Fulvio Tomizza, La miglior vita

1978 - Ferdinando Camon, Un altare per la madre

1979 - Primo Levi, La chiave a stella

1980 - Vittorio Gorresio, La vita ingenua

1981 - Umberto Eco, Il nome della rosa

1982 - Goffredo Parise, Il sillabario n.2

1983 - Mario Pomilio, Il Natale del 1833

1984 - Pietro Citati, Tolstoj

1985 - Carlo Sgorlon, L'armata dei fiumi perduti

1986 - Maria Bellonci, Rinascimento privato

1987 - Stanislao Nievo, Le isole del paradiso

1988 - Gesualdo Bufalino, Le menzogne della notte

1989 - Giuseppe Pontiggia, La grande sera

1990 - Sebastiano Vassalli, La chimera

1991 - Paolo Volponi, La strada per Roma

1992 - Vincenzo Consolo, Nottetempo, casa per casa

1993 - Domenico Rea, Ninfa plebea

1994 - Giorgio Montefoschi, La casa del padre

1995 - Maria Teresa Di Lascia, Passaggio in ombra

1996 - Alessandro Barbero, Bella vita e guerre altrui di Mr. Pyle, gentiluomo

1997 - Claudio Magris, Microcosmi

1998 - Enzo Siciliano, I bei momenti

1999 - Dacia Maraini, Buio

2000 - Ernesto Ferrero, N.

2001 - Domenico Starnone, Via Gemito

2002 - Margaret Mazzantini, Non ti muovere

2003 - Melania G. Mazzucco, Vita

2004 - Ugo Riccarelli, Il dolore perfetto

2005 - Maurizio Maggiani, Il viaggiatore notturno

2006 - Sandro Veronesi, Caos calmo

2007 - Niccolò Ammaniti, Come Dio comanda

2008 - Paolo Giordano, La solitudine dei numeri primi

2009 - Tiziano Scarpa, Stabat Mater

2010 - Antonio Pennacchi, Canale Mussolini

2011 - Edoardo Nesi, Storia della mia gente

2012 - Alessandro Piperno, Inseparabili. Il fuoco amico dei ricordi

2013 - Walter Siti, Resistere non serve a niente

2014 - Francesco Piccolo, Il desiderio di essere come tutti

2015 - Nicola Lagioia, La ferocia

2016 - Edoardo Albinati, La scuola cattolica

2017 - Paolo Cognetti, Le otto montagne

2018 - Helena Janeczek, La ragazza con la Leica

2019 - Antonio Scurati, M. Il figlio del secolo

2020 - Sandro Veronesi, ll colibrì

2021 - Emanuele Trevi, Due vite

2022 - Mario Desiati, Spatriati

2023 - Ada d'Adamo, Come d'aria

2024 - Donatella Di Pietrantonio, L’età fragile

src: wiki

De Premio Strega is de meest prestigieuze Italiaanse literatuurprijs. De prijs wordt sinds 1947 jaarlijks uitgereikt aan het beste fictieboek van een Italiaanse auteur en voor het eerst uitgegeven tussen 1 mei van het vorige jaar en 30 april.

Geschiedenis en selectieprocedure

In 1944 organiseerden Maria en Goffredo Bellonci voor het eerst een literair salon in hun huis in Rome. Deze zondagse bijeenkomsten bevatten al snel de meest notabele personen uit het Italiaanse culturele leven. De groep stond bekend onder de naam Amici della Domenica, de Zondagse vrienden. In 1947 besloten de Belloncis, samen met Guido Alberti, de eigenaar van het bedrijf dat Strega (likeur) produceert, om een literatuurprijs in het leven te roepen, voor het beste Italiaanse fictieboek van het vorige jaar. De winnaar wordt gekozen door de Zondagse vrienden.

Sinds de dood van Maria Bellonci in 1986 werd de organisatie overgenomen door de Fondazione Maria e Goffredo Bellonci. De leden van de vierhonderdkoppige jury worden nog steeds de Zondagse vrienden genoemd. Om een boek in aanmerking te brengen moeten ten minste twee Vrienden hiermee akkoord gaan. De lange lijst met mogelijke winnaars wordt dan uitgedund tot vijf overblijvers. De tweede stemronde, gevolgd door de proclamatie, vindt plaats op de eerste donderdag van juli in het nymphaeum van Villa Giulia in Rome.

In 2006, de zeventigste editie van de Premio Strega, werd een speciale prijs uitgereikt aan de Italiaanse Grondwet, die werd opgetekend in de beginjaren van deze literatuurprijs. De prijs werd in ontvangst genomen door voormalig president van de Italiaanse Republiek Oscar Luigi Scalfaro.

Winnaars

1947 - Ennio Flaiano, Tempo di uccidere

1948 - Vincenzo Cardarelli, Villa Tarantola

1949 - Giambattista Angioletti, La memoria

1950 - Cesare Pavese, La bella estate

1951 - Corrado Alvaro, Quasi una vita

1952 - Alberto Moravia, I racconti

1953 - Massimo Bontempelli, L'amante fedele

1954 - Mario Soldati, Lettere da Capri

1955 - Giovanni Comisso, Un gatto attraversa la strada

1956 - Giorgio Bassani, Cinque storie ferraresi

1957 - Elsa Morante, L'isola di Arturo

1958 - Dino Buzzati, Sessanta racconti

1959 - Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, Il gattopardo

1960 - Carlo Cassola, La ragazza di Bube

1961 - Raffaele La Capria, Ferito a morte

1962 - Mario Tobino, Il clandestino

1963 - Natalia Ginzburg, Lessico famigliare

1964 - Giovanni Arpino, L'ombra delle colline

1965 - Paolo Volponi, La macchina mondiale

1966 - Michele Prisco, Una spirale di nebbia

1967 - Anna Maria Ortese, Poveri e semplici

1968 - Alberto Bevilacqua, L'occhio del gatto

1969 - Lalla Romano, Le parole tra noi leggere

1970 - Guido Piovene, Le stelle fredde

1971 - Raffaello Brignetti, La spiaggia d'oro

1972 - Giuseppe Dessì, Paese d'ombre

1973 - Manlio Cancogni, Allegri, gioventù

1974 - Guglielmo Petroni, La morte del fiume

1975 - Tommaso Landolfi, A caso

1976 - Fausta Cialente, Le quattro ragazze Wieselberger

1977 - Fulvio Tomizza, La miglior vita

1978 - Ferdinando Camon, Un altare per la madre

1979 - Primo Levi, La chiave a stella

1980 - Vittorio Gorresio, La vita ingenua

1981 - Umberto Eco, Il nome della rosa

1982 - Goffredo Parise, Il sillabario n.2

1983 - Mario Pomilio, Il Natale del 1833

1984 - Pietro Citati, Tolstoj

1985 - Carlo Sgorlon, L'armata dei fiumi perduti

1986 - Maria Bellonci, Rinascimento privato

1987 - Stanislao Nievo, Le isole del paradiso

1988 - Gesualdo Bufalino, Le menzogne della notte

1989 - Giuseppe Pontiggia, La grande sera

1990 - Sebastiano Vassalli, La chimera

1991 - Paolo Volponi, La strada per Roma

1992 - Vincenzo Consolo, Nottetempo, casa per casa

1993 - Domenico Rea, Ninfa plebea

1994 - Giorgio Montefoschi, La casa del padre

1995 - Maria Teresa Di Lascia, Passaggio in ombra

1996 - Alessandro Barbero, Bella vita e guerre altrui di Mr. Pyle, gentiluomo

1997 - Claudio Magris, Microcosmi

1998 - Enzo Siciliano, I bei momenti

1999 - Dacia Maraini, Buio

2000 - Ernesto Ferrero, N.

2001 - Domenico Starnone, Via Gemito

2002 - Margaret Mazzantini, Non ti muovere

2003 - Melania G. Mazzucco, Vita

2004 - Ugo Riccarelli, Il dolore perfetto

2005 - Maurizio Maggiani, Il viaggiatore notturno

2006 - Sandro Veronesi, Caos calmo

2007 - Niccolò Ammaniti, Come Dio comanda

2008 - Paolo Giordano, La solitudine dei numeri primi

2009 - Tiziano Scarpa, Stabat Mater

2010 - Antonio Pennacchi, Canale Mussolini

2011 - Edoardo Nesi, Storia della mia gente

2012 - Alessandro Piperno, Inseparabili. Il fuoco amico dei ricordi

2013 - Walter Siti, Resistere non serve a niente

2014 - Francesco Piccolo, Il desiderio di essere come tutti

2015 - Nicola Lagioia, La ferocia

2016 - Edoardo Albinati, La scuola cattolica

2017 - Paolo Cognetti, Le otto montagne

2018 - Helena Janeczek, La ragazza con la Leica

2019 - Antonio Scurati, M. Il figlio del secolo

2020 - Sandro Veronesi, ll colibrì

2021 - Emanuele Trevi, Due vite

2022 - Mario Desiati, Spatriati

2023 - Ada d'Adamo, Come d'aria

2024 - Donatella Di Pietrantonio, L’età fragile

src: wiki

Land: ITA

Lumumba in the Arts, Edited by Matthias De Groof

ID: 202001211471

"Art reminds us of the impossibility of his death and leaves us horrified every time one remembers the tragedy.", Matthias De Groof, editor 'Lumumba in the Arts'

"Art reminds us of the impossibility of his death and leaves us horrified every time one remembers the tragedy.", Matthias De Groof, editor 'Lumumba in the Arts'Lumumba as a symbol of decolonisation and as an icon in the arts

It is no coincidence that a historical figure such as Patrice Emery Lumumba, independent Congo’s first prime minister, who was killed in 1961, has lived in the realm of the cultural imaginary and occupied an afterlife in the arts. After all, his project remained unfinished and his corpse unburied. The figure of Lumumba has been imagined through painting, photography, cinema, poetry, literature, theatre, music, sculpture, fashion, cartoons and stamps, and also through historiography and in public space. No art form has been able to escape and remain indifferent to Lumumba. Artists observe the memory and the unresolved suffering that inscribed itself both upon Lumumba’s body and within the history of Congo. If Lumumba – as an icon – lives on today, it is because the need for decolonisation does as well.

Rather than seeking to unravel the truth of actual events surrounding the historical Lumumba, this book engages with his representations. What is more, it considers every historiography as inherently embedded in iconography. Film scholars, art critics, historians, philosophers, and anthropologists discuss the rich iconographic heritage inspired by Lumumba. Furthermore, Lumumba in the Arts offers unique testimonies by a number of artists who have contributed to Lumumba's polymorphic iconography, such as Marlene Dumas, Luc Tuymans, Raoul Peck, and Tshibumba Kanda Matulu, and includes contributions by such highly acclaimed scholars as Johannes Fabian, Bogumil Jewsiewicky, and Elikia M’Bokolo.

Contributors: Balufu Bakupa-Kanyinda (artist), Karen Bouwer (University of San Francisco), Véronique Bragard (UCLouvain), Piet Defraeye (University of Alberta), Matthias De Groof (scholar/filmmaker), Isabelle de Rezende (independent scholar), Marlene Dumas (artist), Johannes Fabian (em., University of Amsterdam), Rosario Giordano (Università della Calabria), Idesbald Goddeeris (KU Leuven), Gert Huskens (ULB), Robbert Jacobs (artist), Bogumil Jewsiewicki (em., Université Laval), Tshibumba Kanda Matulu (artist), Elikia M’Bokolo (EHESS), Christopher L. Miller (Yale University), Pedro Monaville (NYU), Raoul Peck (artist), Pierre Petit (ULB), Mark Sealy (Autograph ABP), Julien Truddaïu (CEC), Léon Tsambu (University of Kinshasa), Jean Omasombo Tshonda (Africa Museum), Luc Tuymans (artist), Mathieu Zana Etambala (AfricaMuseum)

This publication is GPRC-labeled (Guaranteed Peer-Reviewed Content).

Land: COD

Gallimard stopt met uitgaven van Gabriel Matzneff wegens pedofiele geschriften.

ID: 202001111623

Land: FRA

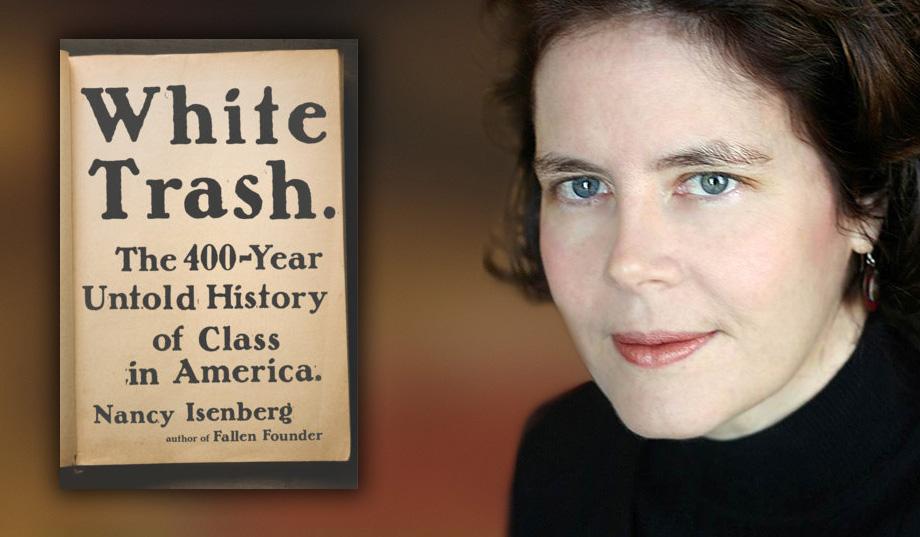

White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America

ID: 201606210914

In her groundbreaking history of the class system in America, extending from colonial times to the present, Nancy Isenberg takes on our comforting myths about equality, uncovering the crucial legacy of the ever-present, always embarrassing––if occasionally entertaining––"poor white trash."

The wretched and landless poor have existed from the time of the earliest British colonial settlement. They were alternately known as “waste people,” “offals,” “rubbish,” “lazy lubbers,” and “crackers.” By the 1850s, the downtrodden included so-called “clay eaters” and “sandhillers,” known for prematurely aged children distinguished by their yellowish skin, ragged clothing, and listless minds.

Surveying political rhetoric and policy, popular literature and scientific theories over four hundred years, Isenberg upends assumptions about America’s supposedly class-free society––where liberty and hard work were meant to ensure real social mobility. Poor whites were central to the rise of the Republican Party in the early nineteenth century, and the Civil War itself was fought over class issues nearly as much as it was fought over slavery.

Reconstruction pitted "poor white trash" against newly freed slaves, which factored in the rise of eugenics–-a widely popular movement embraced by Theodore Roosevelt that targeted poor whites for sterilization. These poor were at the heart of New Deal reforms and LBJ’s Great Society; they haunt us in reality TV shows like Here Comes Honey Boo Boo and Duck Dynasty. Marginalized as a class, "white trash" have always been at or near the center of major political debates over the character of the American identity.

We acknowledge racial injustice as an ugly stain on our nation’s history. With Isenberg’s landmark book, we will have to face the truth about the enduring, malevolent nature of class as well.

(source:goodreads)

Land: USA

Wereldliteratuur op tijdlijn geplaatst

ID: 201602030957

In 'Categories' (Search pagina) werd LITERATURE WORLD gerangschikt op het jaar van de eerste oorspronkelijke editie van de weerhouden titel.

In 'Categories' (Search pagina) werd LITERATURE WORLD gerangschikt op het jaar van de eerste oorspronkelijke editie van de weerhouden titel.Zo maken we een reis door de tijd, beginnend bij Xenofon (398 v. Chr.) tot Maamoura (2010). In totaal worden 388 titels (incl. dubbels) gepresenteerd.

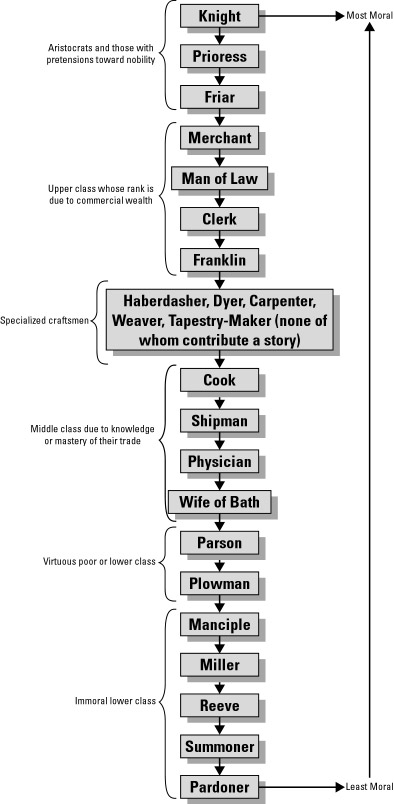

The Canterbury Tales - character map

ID: 201405010152

Land: GBR

The Nobodies

ID: 201404122011

'Fleas dream of buying themselves a dog, and nobodies dream of escaping poverty: that, one magical day, good luck will suddenly rain down on them – will rain down in buckets. But good luck doesn’t rain down, yesterday, today, tomorrow or ever. Good luck doesn’t even fall in a fine drizzle, no matter how hard the nobodies summon it, even if their left hand is tickling, or if they begin the new day on their right foot, or start the new year with a change of brooms. The nobodies: nobody’s children, owners of nothing. The nobodies: the no-ones, the nobodied, running like rabbits, dying through life, screwed every which way. Who are not, but could be. Who don’t speak languages, but dialects. Who don’t have religions, but superstitions. Who don’t create art, but handicrafts. Who don’t have culture, but folklore. Who are not human beings, but human resources. Who do not have faces, but arms. Who do not have names, but numbers. Who do not appear in the history of the world, but in the crime reports of the local paper. The nobodies, who are not worth the bullet that kills them.'

— Eduardo Galeano, "The Nobodies"

Galeano, a literary giant of the Latin American left.

— Eduardo Galeano, "The Nobodies"

Galeano, a literary giant of the Latin American left.

Land: URY

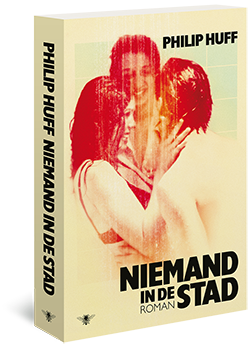

Niemand in de stad - roman

ID: 201200003588

Philip Hofman woont in het Weeshuis, een statig studentenhuis aan de Amsterdamse Prinsengracht. De twaalf bewoners hebben daar, buiten het blikveld van de maatschappij, hun ouders en hun vriendinnen, een vrijplaats gecreëerd.

Philips beste vrienden zijn huisgenoten Matt en Jacob, de eerste een impulsieve hartenbreker, de tweede een beschouwende intellectueel. Door hen aangespoord laat Philip zich steeds meer meeslepen in het studentenbestaan.

Niemand in de stad is een roman over vriendschap, vreemdgaan, liefde, een meedogenloze stad en de tol van verkeerde verwachtingen.

DE PERS OVER NIEMAND IN DE STAD

‘Met Niemand in de stad betoont Philip Huff zich als een literaire nakomeling van de grote Nescio en diens Uitvreter.’ – de Volkskrant

‘Geweldig geschreven roman [vol] krankjoreme dialogen en absurdistische sfeerbeschrijvingen waar Huff als een circusartiest mee jongleert.’ – NRC Handelsblad

‘Om dat goed te kunnen doen, de lezer interesseren èn beroeren, moet je goed kunnen schrijven. En dat kan Huff.’ – De Groene Amsterdammer

‘Mooie passages over liefde, verliefdheid en vriendschap.’ – Vrij Nederland

‘Een Bij nader inzien van onze jaren’. – Leeuwarder Courant

‘Eindelijk lees je ook weer eens goede seks in een boek, geen porno of zo, verre van, maar gewoon goede seks. Voorop staat echter dat Niemand in de stad een geweldig rijke roman is die je blij maakt vanwege de zoveelste jonge gast (27!) die schrijft als een jonge god.’ – Limburgs Dagblad

Land: NLD

Half a Brain is Enough - The Story of Nico

ID: 200611061451

Part of Cambridge Studies in Cognitive and Perceptual Development

AUTHOR: BATTRO, Argentine Academy of EducationDATE PUBLISHED: November 2006AVAILABILITY: Available FORMAT: Paperback

ISBN: 9780521031110

Half A Brain Is Enough is the moving and extraordinary story of Nico, a little boy who at the age of three was given a right hemispherectomy to control intractable epilepsy. Antonio Battro, a distinguished neuroscientist and educationalist, charts what he calls Nico's 'neuroeducation' with humour and compassion in an intriguing book which is part case history, part meditation on the nature of consciousness and the brain, and part manifesto. Throughout the book Battro combines the highest standards of scientific scholarship with a warmth and humanity that guide the reader through the intricacies of brain surgery, neuronal architecture and the application of the latest information technology in education, in a way that is accessible and engaging as well as making a significant contribution to the current scientific literature. Half A Brain Is Enough will be compulsory reading for anyone who is interested in the ways we think and learn.

Fascinating and moving account of one boy's recovery and education following major brain surgery

Explores topics such as evolution of the brain, the way the brain works, consciousness, the use of computers in education

Complex science yet written in an engaging and accessible way will appeal to academics and professionals, as well as the general reader.

Ziehier de berichtgeving van TROUW:

In het boek ’Half a brain is enough’ beschrijft de arts Antonio Battro het geval van het jongetje Nico. Nico had heftige epileptische aanvallen in de rechterhersenhelft. Zo heftig, dat er voor zijn overleving niets anders op zat dan een ingrijpende hersenoperatie.

Nico was bij de operatie drie jaar en zeven maanden oud. Eerst werd zijn volledige slaapkwab weggehaald. Wat er van zijn rechterhersenhelft nog overbleef, werd losgesneden van de linkerhersenhelft en van de hersenstam. Dit deel werd niet verwijderd, maar functioneerde niet meer. Als volwassene zal hij het moeten doen met de helft van de normale 1400 gram hersenen.

Na de operatie kon Nico in eerste instantie niet lopen. Maar vijf jaar later rent en speelt hij vrij normaal, alleen een beetje trekkebenend. Wel beweegt zijn linkerarm moeilijk en ziet hij niks in de linkerhelft van zijn gezichtsveld. Met die relatief kleine handicaps kan hij echter goed omgaan. Maar dan het opmerkelijke: Nico’s cognitieve, sociale en emotionele vermogens verschillen niet wezenlijk van die van zijn leeftijdgenoten. Zijn talige vermogens –typisch een vermogen van de linkerhersenhelft– liggen zelfs ruim boven het gemiddelde.

De crux zit in het aanpassingsvermogen van Nico’s overgebleven hersenhelft. Hoe dat precies werkt, is nog onbekend. Specifieke training is wel essentieel. Vermogens die typisch worden geassocieerd met de weggehaalde rechterhersenhelft –onder andere wiskunde, beeldende kunst, muziek– zijn overgenomen door de overgebleven linkerhersenhelft. En hoewel Nico voor die vaardigheden geen speciale aanleg heeft, is hij er ook niet slechter in dan de gemiddelde leeftijdgenoot. Nico had het geluk dat hij op zo’n jonge leeftijd werd geopereerd. Dat beperkte zijn functieverlies nog enigszins.

Wereldwijd zijn er ongeveer honderd patiënten bij wie vanwege heftige epilepsie een hersenhelft is verwijderd. Ook de Duitser Philipp Dörr leed zo zwaar aan epilepsie dat artsen geen andere oplossing zagen dan het verwijderen van de rechterhelft van zijn grote hersenen. Dörr was bij de operatie al elf jaar. Net na de operatie waren alle functies die vroeger door de rechterhelft werden gedaan, verdwenen. Drie jaar revalideerde Dörr na de operatie in het ziekenhuis, een veel langere revalidatieperiode dan bij Nico. Maar ook bij de Duitser bleek de flexibiliteit van het brein verrassend groot.

Hoewel Dörr veel herinneringen mist uit de jaren vóór de operatie, bleken zijn intellectuele vaardigheden nauwelijks onder de verwijdering van de rechterhersenhelft te hebben geleden. Zijn IQ is normaal. Praten en schrijven kan hij nog steeds. Hij schaakt en leest romans. Alleen als zijn brein veel taken tegelijk moet verwerken, heeft hij daar duidelijk moeite mee.

Ja, je kunt dus leven met één hersenhelft. Wat trouwens niet betekent dat er geen functies verloren gaan, of dat we, zoals een hardnekkige mythe beweert, maar de helft of zelfs maar 10 procent van onze hersenen zouden gebruiken. Het betekent wel dat de flexibiliteit van onze hersenen groter is dan we lang hebben gedacht.

wikipedia en Espagnol

see also Awakenings

Achieving Our Country - Leftist Thought in Twentieth-Century America

ID: 199908270286